As the scene opens, a brief shot catches a spy momentarily transfixed by a painting. That spy is James Bond, and that painting is Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire tugged to her last berth to be broken up, 1838. Soon the as-yet-unidentified Q sits down to offer his barbed reading, and it hits close to home. Stung, Bond refuses to interpret the work of high Romantic elegy that had held his attention moments before—it’s just “a bloody big ship.” This denial is a concession: Bond tacitly admits the painting depicts what Q calls “the inevitability of time.”

Continue reading “Elegy in Wordsworth, Turner, and James Bond”

The Resonance of the Veil: Some Thoughts about Methodology

By Caroline Winter

For most of my academic career, I didn’t think much about methodology. I read, I think, I write (and rewrite, rewrite, rewrite). This changed when I took an introductory Digital Humanities course, a survey of digital tools and methods. My biggest takeaway from this course (other than that computers are frustrating) was that methodology affects not only the results of research, but also the way we think about our data and the types of questions we ask. This not a new idea for many scholars, I know, but for those of us used to the read-think-write strategy, it bears thinking about.

Continue reading “The Resonance of the Veil: Some Thoughts about Methodology”

Sleep, Dreams, and Poetry

Endymion is one of the funniest heroes in Romantic poetry, mainly because he is so frequently fainting and falling asleep. He sleeps so often that I struggle to separate his waking and sleeping, a common problem for Keats that I want to talk about in this post. I have written previously about shared feeling and cognition, and dreaming is a particularly interesting case study for these topics, I think.

Let me catch you up to the ideas I’ve been toying with for my dissertation. I have come to believe that for Keats communion across time and space is enabled by acts of reading and the shared feelings reading encourages. Feelings circulate, via a text, among the bodies engaged in acts of reading (or other aesthetic experiences), and feeling is always an embodied cognitive experience. Therefore communion is realized (not just imagined) in the embodiment of transferred or circulated affect, a reactivation or revitalization of feelings in the moment of reading. From these assumptions, I begin my study of sleep and dreams. Continue reading “Sleep, Dreams, and Poetry”

The Art of the Book and Romanticizing Landscape

For several months now, I have had the pleasure to work on a project with my friend and fellow artist Cat Snapp. On a Texas summer evening, we discussed over dinner our overlapping interests in the outdoors and the influence it has on our work. Through connection to the geological past or ties to personal culture, we each use print media to speak about the personal, historical, and psychological relationships we have with the world around us. At a certain point, we realized that the project that would best unite our voices and express the feeling we wanted was a letterpress printed artist’s book. It has the power to be intimate with the reader, yet it transcends the starkness of simple text on a page – it can reach into places travelled and landscapes desired.

Continue reading “The Art of the Book and Romanticizing Landscape”

Romantic Web Communities

One of the great advantages we have as scholars is the opportunity to form communities beyond our institutions — not just at annual conferences in remote locales, but also in ongoing conversations on the web. These online communities are fora for scholarly dialogue and informal queries, requests for crowdfunding special projects and historical sites, and repositories of archival material. Here’s a brief roundup of selected sites, listservs, and communities available to Romanticists (and if you know of more, please get in touch!).

Academic listservs:

(1) NASSR List — the list of the North American Society for the Study of Romanticism (subscription required). The list is frequented by many major scholars in the field, but also graduate students and junior faculty; this is a particularly excellent resource for answers to obscure and arcane historical questions, and for links to major awards and opportunities in the field. Continue reading “Romantic Web Communities”

Graphic Learning: Examples of Well-Researched Comics

It seems pointless to argue that graphic novels have an important place in literature at this point. Personally, I took two classes during my undergraduate career that incorporated such texts (including Satrapi’s Persepolis and Bechdel’s Fun Home), but more often than not this is a rare occurrence and something I did not encounter in my graduate coursework. Graphic novels often do not get the attention they deserve, in part because many deem them déclassé due to their graphic nature and/or subject material, but also because they are hard to teach. While graphic novels can be analyzed through literary theory (and should be), the format itself, and most notably, the visual element of such narratives, are in a scholarly discipline all their own. One cannot teach, or even fully enjoy a graphic novel, without at least a bare minimum knowledge of art theory and visual composition. (Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art and Critical Approaches to Comics: Theories and Methods are good places to start.) But then again, neither of these things occupies some alien universe detached from what we as literary scholars already tackle. Continue reading “Graphic Learning: Examples of Well-Researched Comics”

Planning My First Brit Lit Survey

At my university, the opportunities to teach an upper-level course are present but few. After passing comprehensive exams, you can apply to teach a survey course corresponding to your area of specialty. The second-half of British literature is particularly hard to come by, and typically a PhD candidate gets to teach it once before graduating. This is my semester, and I am thrilled!

I have been teaching general education classes for six years. I can count the number of English majors I have taught on one hand. But now, I have two full classes of English majors or minors, who ask me questions like, “Percy Shelley? Any relation to Mary Shelley?” (Isn’t it crazy to remember a time when we didn’t know every intimate detail of the Shelleys’ marriage?).

I am two days in. And here’s what I can report so far: I love my job.

Continue reading “Planning My First Brit Lit Survey”

Rethinking Romantic Media: Print Alternatives

While my research has thus far focused on Romantic print media, my recent foray into the world of media archeology has led me to search for alternative media that print obscures. In Gramaphone, Film, Typewriter, Friedrich Kittler confronts “the historian’s writing monopoly” (6) by arguing that print cannot adequately take into account oral and visual culture. Writing merely stores the “facts of its authorization” (7), while “whatever else was going on dropped through the filter of letters and ideograms” (6). Kittler points to photography and film as storage media that put an end to the monopoly of print by recording the images and noise that print filters out. And yet, for scholars like ourselves interested in the period that preceded these inventions, how do we uncover the alternative media that print obscures? In order to answer this question, I turn to two examples of performance-based media that much recent work has attempted to reconstruct: lecture and drama.

Reconstructing the Romantic lecture

On February 28, 2014, the University of Colorado at Boulder hosted “Orating Romanticism,” a series of speakers that included Dr. Sarah Zimmerman of Fordham University, Dr. Sean Franzel of the University of Missouri, and CU Boulder’s own Kurtis Hessel. While each speaker focused on a particular lecturer or series of lectures, all spoke about the challenges they face when attempting to reconstruct a medium that is inherently performative and ephemeral. Dr. Zimmerman explained that Romantic lectures were critical oral arguments shaped by participating auditors as much as speakers themselves. For example, when giving a series of lectures on Shakespeare’s characters at the Royal Institution, Coleridge frequently deviated from his notes and occasionally strayed so far from the advertised topic that auditors complained in their reviews. Other lecturers changed their topics according to the audience’s immediate responses, collapsing the time between composition and reception that characterizes print. Working with such a medium proves challenging, explained Zimmerman, because the lecture’s “authoritative text,” if such a thing exists, “lies at the midpoint that marks the exchange between performer and audience.” As an inherently performative media dependent on time, place, and audience, the Romantic lecture cannot be adequately expressed in print.

Facing this challenge in his work on Coleridge’s, Hazlitt’s, and Humphry Davy’s respective lectures, Kurtis Hessel explained that in order to reconstruct these events we’re forced to cobble together “texts” from various sources, including the speaker’s notes, advertisements, reviews, and writings of those who attended. And yet, cautioned Hessel, these sources are often unreliable indicators of what actually took place. Just because a lecture was advertised, for example, does not mean it was actually held. If ticket sales failed to reach certain quotas, the event was canceled. In addition, while some lecturers like Hazlitt published write-ups of their lectures following the event, the printed version does not necessarily provide an accurate account of the lecture itself. Although it’s tempting to treat lectures in the same way we treat texts, Hessel struggles against this inclination in his work. Rather than relying on an available text, he explained, we’re forced to construct one. While print continues to dominate our understanding of Romantic-era oral media, we should seek out as many diverse sources as possible in order to reconstruct these moments. The lecture itself exists somewhere in between.

Reconstructing drama and pantomime

Drama is a similarly performative medium that presents methodological challenges when reconstructing it in print. With the exception of closet dramas and other plays that were not intended for the stage, the majority of popular stage productions were written with performance in mind. Although we have scripts, stage directions, and other textual remnants of these works, it’s difficult to imagine what occurred at individual performances. In Coleridge’s highly successful drama Remorse (1813), for example, we know that audiences were enthralled by a spectacular incantation scene in which an altar goes up in flames to reveal a painting of the protagonist’s assassination. Yet no surviving versions of the text give any indication of how this effect was achieved. Instead, our best guess comes from a write-up in The Examiner that describes “the altar flaming in the distance, the solemn invocation, the pealing music of the mystic song,” that together produced “a combination so awful, as nearly to over-power reality, and make one half believe the enchantment which delighted our senses.” Though lacking in specifics, this description depicts the scene better than the play’s stage directions, which simply read “The incense on the altar takes fire suddenly, and an illuminated picture of Alvar’s assassination is discovered.” In cases where stage spectacle played an important role in a production, paratextual materials are often better approximations of performance than the text itself.

These materials become even more important in the reconstruction of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century pantomime, a form characterized by on-stage action rather than dialogue. When trying to reconstruct the text of Harlequin and Humpo (1812) for The Broadview Anthology of Romantic Drama, Jeffrey Cox and Michael Gamer used manuscripts with short descriptions of scenes alongside audience programs and other detailed information, but it’s impossible to arrive at an “ideal text” when a performance has no words. In places where the manuscript had little detail, they looked for descriptions in newspaper reviews. One review reveals that an Indian boy performed impressive contortions and acrobatics for a good portion of Scene V, a sequence that isn’t mentioned in the manuscript and seems have been a last minute addition to the show. It’s the piecing together of these sources that gives us the closest possible approximation of the work.

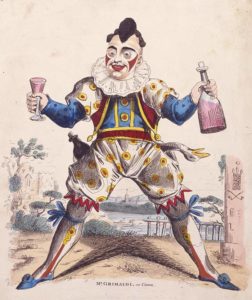

- Joseph Grimaldi as “Clown,” an archetypal character in pantomime, c. 1810. (Wikipedia)

Destabilizing print

Despite my desire to uncover alternatives to print media, to deconstruct Kittler’s “writing monopoly,” it’s obvious that print is all that remains of Romantic performance culture. And yet, in our efforts to cobble together “texts” of these lectures and plays, it becomes harder to uphold traditional notions of textual stability. Especially in instances where there are multiple versions with significant differences, books are characterized by variation, difference, and inconsistency rather than grand solidity and authority. While publishers tend to smooth over these ruptures in “definitive editions” of canonical texts, reconstructions of forms like lecture and drama refuse to lull the reader into a fall sense of continuity. The search for Romantic print alternatives, though perhaps futile, may lead us to a more nuanced understanding of the different forces at play within printed texts.

Use Value and Literary Work: Poetic Identity in 19th Century Britain

I am a few days from submitting a full draft of my Ph.D. comprehensive exam rationales. These short written explanations/defenses of my lists are intended to help my committee see how I chose my texts, how I conceptualize the time periods, and what kinds of questions to pose in my oral exam next month. No pressure, right? I am not required as of yet to make groundbreaking strides in our field. (I have four months until the dissertation proposal is due.) For now, I am to demonstrate a confident knowledge of the area and its current critical debates.

And I must say, despite all odds: I am really enjoying this process. I mean REALLY enjoying it.

Months upon months ago, I began designing my lists according to major themes in Romanticism and Victorianism. I borrowed this approach from an old Victorian lit syllabus that divided our readings into the major debates of the period. Luckily, the Victorian epoch already has names for many of these debates– we get “the woman question” and “the condition of England.” I started there and tried to work backward to see similar debates in Romanticism. Not impossible, but I eventually abandoned these categories, finding many texts too difficult to compartmentalize. Within and across the lists, I found too much resistance to these neat categories.

The porous boundaries between literary movements or cultural epochs are a consistent point of debate in literary studies. (This acknowledgment heads the disclaimer we sign upon entering grad school, right? “We all know this fact, but you, grad student, are responsible for challenging these textual boundaries in intelligent and original ways for the next six years”). The long-nineteenth century in British literature itself must expand at both ends to encompass a least a decade in each direction to make adequate sense in the ways we critics currently construct the period. And this is not a phenomenon reserved for the afterlife of each movement alone, but rather the writers and theorists of the Romantic and Victorian movements look backward and forward in attempts to situate themselves and their literature within a cultural narrative that shapes and is shaped by their work. Indeed, what I find definitive of the nineteenth century, a point of connection that unites the various authors and genres represented in my comprehensive exam lists, is a desire for clear situation within and beyond an epoch.

The writers we study desire a lasting cultural influence. They seek to shape and correct, to play a significant role in cultural formation and the national story. I argue that this desire to influence and make a mark is a symptom of economic insecurity. With an emphasis on practicality and pragmatism (the use-value of work) as the bourgeois class rises to influence across the Romantic and Victorian epochs, the “word’s worth,” if you will, of a man or woman of letters seems to require its own proof. This need to defend and define one’s usefulness in society and to posterity (on top of the need to prove one’s self within a chosen vocation, as with Keats, Hunt, DeQuincey and numerous women writers like Mary Robinson) creates a significant identity crisis that gets translated across the century into various points of cultural and historical contention.

John Guillory writes a compelling history of “use value,” how it was invented and how it comes to odds against aesthetic value in the early nineteenth century. I came to Guillory through Mary Poovey’s brilliant 2008 book Genres of the Credit Economy. Hers is a book you read and pine over, jealous you hadn’t written it first. Of course the list of books I wish I had written has grown well beyond anything I could reasonably produce in a long academic career; nonetheless, I continue to drool and dream. Teasing out what Poovey calls a “double-discourse of value,” Guillory argues that aesthetic value depended on the emergence of “use value” as an economic concept in the late eighteenth century. Looking to Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments and Wealth of Nations, Guillory states that use value was invented to discursively clarify the relationship between production and consumption. It seems the people—literary writers and theorists?—were uncomfortable with the affective motivation behind ascribing a product value. Under the increased pressure for utility and practicality, valuing a work of art because of the pleasure it brings seemed a tenable (at best) justification for the time and effort expended in producing and consuming it. Therefore, the discourse substituted in use value which seems to marry production and consumption and get rid of the warm, fuzzy emotional value of art.

At the same time, Literature with a capital “L” cannot become so useful as to be absorbed into other types of writing like economic, scientific, or political writing (here’s the heart of Poovey’s book– how the distinctions arose between the genres). So here’s the rub—aesthetics branches off from economic discourse for the first time, reiterating that not all written products are works of art. But what’s more, the products that appear like works of art may not be. Thus Literary writers define what is “fine art” and distinguish between types of imaginative production based upon their adherence to the definition (namely, a work should not call attention to itself as a commodity, so rule out popular works and works of “immediate utility”).

But does this dismissal of “immediate utility” give leeway enough for my argument that poets and novelists in the nineteenth century feel the need to prove their utility? I say, absolutely yes. In my own adaptation of this cultural narrative, this is the crux of poetic identity in crisis. Suddenly (or not so suddenly, really, but now of sudden we have the language to explain this phenomenon) literature’s worth can no longer be taken as indisputable fact. Suddenly, artists must defend the cultural relevance of the work. What work does Literary work perform? Ironically, Wordsworth’s Prelude (esp. the 1805 version) justifies his seemingly self-indulgent aesthetic exercise in tracing the development of the poetic genius as performing the cultural work of a natural philosopher or historian, as he uses himself as the case study of a mind in development during upheaval of the French Revolution. Similarly, guarding his work against accusations of sensationalism or shock value, DeQuincey justifies his Confessions as being a comprehensive (scientific?) study of the effects of opium consumption, adding the potential educational benefits his mistakes may provide for the reader.

Perhaps more interestingly, Victorians like Thomas Carlyle and Matthew Arnold seek to define a use value for the aesthetic products more obviously abstracted from immediate utility than Wordsworth’s or DeQuincey’s. Here we have a sense of immediate cultural crisis—the moral fabric of society is degrading as the class boundaries seem to be dissolving, gender roles (especially in the literary marketplace) seem to be in flux, science is questioning what it means to be human (and to be particular kinds of humans, etc). Carlyle and Arnold foresee anarchy, and they don’t seem too extreme with these concerns. Radical individualism, as Carlyle terms it “democracy,” erases the need for leaders to model correct behavior. And what will we do without models? How can we possibly be moral without seeing what morality is? How can we be cultured if everything and everyone is valued equally? Carlyle’s answer: heroes and hero worship. And significantly, his heroes always have a poetic sensibility, that is when his heroes are not poets themselves. Likewise, Arnold famously writes that culture is the answer to anarchy. To read and see all the best that has been known and created–this will civilize and make moral the British populace in flux.

I can see these economic questions of “work” and “value” at the root of my original categories, the major crises of the nineteenth century in British culture. I feel as though this framework lends itself to a discussion of so many topics in recent scholarship: mental science, gendered work (domestic novels vs. fin de siècle adventure novels; sensibility and sentimentalism; etc.), professionalization of bourgeois occupations, dissenting culture, the widening franchise, the bard’s role in nation-making and historical record, scientific advancement and religious doubt, etc.

All this to say, I am arguing a relationship between economic and social (class) change as the root of writers’ identities. I see the common thread between nineteenth century writers as their struggle to negotiate aesthetic vocations within a market and within a society that seeks a use value for all products (read utilitarianism, read Victorian work ethic, read rise of bourgeois values). Meanwhile every fiber of their beings wants to privilege fine art above products with an immediate utility. Fine art is for posterity, it is lasting and transcendent. Okay so “every fiber” is a gross overstatement, and my actual narrative challenges this art for art’s sake assumption. Ultimately, there is a real anxiety about whether literary work performs a cultural service, and these writers vie for recognition of their worth both personally and occupationally, both in the moment and in literary history.

Rethinking Romantic Textualities with Media Archeology

In my first post for this blog, I wrote about how my background in archeology influences my perception of texts as physical objects, and how I’d like to move towards an “archeological hermeneutics” that takes into account a text’s material conditions as contributing to its contents and their significance. Moving forward, I’d like to complicate our understanding of text-as-object by introducing what I’ve so far learned in my “Media Archeology” seminar taught by Lori Emerson. It came as a surprise to my family and friends that I enrolled in this course, because I tend to take classes that focus on the study of 18th and 19th century literatures. Although I won’t be reading any texts “in my period” for this class, I’ve found it has in fact supplied me with a variety of alternative methodologies for my Romantic-era research.

Although those who work in the field tend to resist a concrete definition, Jussi Parikka calls media archeology “a way to investigate the new media cultures through insights from past new media, often with an emphasis on the forgotten, the quirky, the non-obvious apparatuses, practices and inventions” (Parikka loc 189). We’re encouraged to take apart machines in order to understand how they operate, and in turn expose the conditions and limits of our technologically mediated world. Relying on Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, among other texts, media archeologists expose structures of power embedded within the hardware of modern technology, revealing the ways in which media exert control over communication and provide the limits of what can be said and thought.

I find this way of thinking about the structures and limitations imposed by media particularly useful for the study of 18th and 19th century texts. Instead of thinking about how printing and publication practices give rise to individual texts, as I have in the past, I’ve started to consider texts from the inside out: what do books tell us about the cultural conditions and constraints imposed by the media in which they were (and are) written, manufactured, and consumed? Like the ASU Colloquium’s post, I wonder what three volume novels, for example, might tell us about communal reading practices and circulation of texts and, importantly, our modern reading practices in comparison. I’d hypothesize that circulating texts and libraries would contribute to communities of readers in which reading was, perhaps, a shared experience. In contrast, modern reading tends to be solitary experience which involves owning texts (especially when the library has only one copy of the book you need).

I’ve also found media archeology’s rethinking of linear time and notions of progress particularly useful and interesting. Collapsing “human time” allows us to bring together seemingly unrelated technologies for comparison and analysis. I’m thinking here of the Amazon Kindle and 18th century circulating libraries, which both create spaces for communal reading. In contrast to the private reading practices I described above, I think the Kindle – and specifically the “popular highlight” feature – presents an opportunity for readers to become aware of their participation in collective readerships. When you click on a pre-underlined sentence, it shows how many other people have also highlighted it. While at first I found this feature annoying – perhaps evidence of the private relationship I tend to have with books – I’ve begun to enjoy the way it makes me aware that I’m one of many readers who’s enjoying this particular text. Furthermore, I wonder if my newfound sense of collective readership would also give me a better understanding of Romantic-era reading practices that were likewise characterized by shared texts and mutual engagement. The ASU Colloquium posed an important question about whether we should attempt to read texts as their original readers would have; since many of us no longer have access to the original 3 volume novels and their circulating libraries, maybe we can gain insight into these texts and reading practices from the vantage point of our own collaborative technologies.

To close this post, I want to introduce one more concept from my media archeology reading that I’ve also found particularly applicable to the study of Romanticism: glitch aesthetics. Typically understood as accidents and hick ups within games, videos, and other digital media, glitch artists exploit them in order to “draw out some of [that technology’s] essential properties; properties which either weren’t reckoned with by its makers or were purposefully hidden” (McCormack 15). Again, media archeologists are concerned with exposing the power structures embedded in technologies, this time by giving us a peek of what lies beneath. While looking at glitch art, I couldn’t help but think of an experience I’d had in the British Library reading Keats’s manuscripts. I remember finding an additional verse to “Isabella: Or, the Pot of Basil” in George Keats’s notebook in what I think was Keats’s hand etched nearly invisible on the opposite page. Of course, this mysterious stanza threw a wrench in the carefully constructed argument I’d planned, and I had no idea what to make of it. Now that I look back on it, I’d like to think of that stanza as a textual glitch – it’s possible that Keats never intended for it to be read. Perhaps it had even been erased from the page. For me, this “glitch” reveals the textual instability of the poem and disrupts the sense of solidity and permanence with which I’ve come to regard Keats’s oeuvre.

I still have much to learn about media archeology and its methodologies (which I’ve certainly oversimplified), but I think this field could lead our work in Romanticism in new and exciting directions.