It’s that time of year when we come together with those close to us to celebrate, before the year ends, the things that really matter… like conference proposals (NASSR’s is due January 17th!), chapter drafts, readings from new books, and the other standard fare of the nineteenth-century working group. But concocting the perfect colloquium moves beyond a craft to become an art form, and it is the aim of this post to give you some pointers on preparing that rare colloquium that is truly — well done.

Continue reading “The Joy of Colloquium: Recipes for Workshop Success”

On Starting a Reading Group

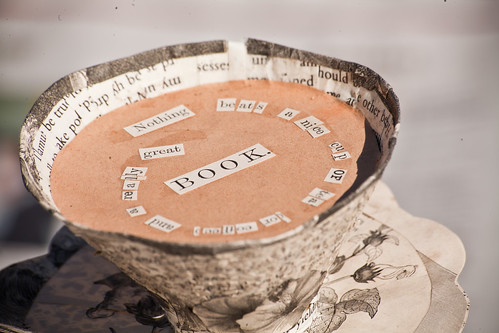

Once I’d finished my coursework requirements, I found myself really missing the chance to regularly gather with fellow grad students and talk about reading. Studying for exams and writing the dissertation can be isolating experiences. Some large programs may have a few students studying or writing within similar fields, but smaller programs don’t always have this kind of ready-made specialized community. Even so, it can be refreshing to chat analytically and appreciatively about literature with others, even if that literature is outside your particular interests. Aside from just hanging around the office and asking, “Read any good books lately?” the best way I’ve found to foster this type of discussion is to start and join reading groups.

Once I’d finished my coursework requirements, I found myself really missing the chance to regularly gather with fellow grad students and talk about reading. Studying for exams and writing the dissertation can be isolating experiences. Some large programs may have a few students studying or writing within similar fields, but smaller programs don’t always have this kind of ready-made specialized community. Even so, it can be refreshing to chat analytically and appreciatively about literature with others, even if that literature is outside your particular interests. Aside from just hanging around the office and asking, “Read any good books lately?” the best way I’ve found to foster this type of discussion is to start and join reading groups.

Planning your group:

Numbers are important. If you put out a call for interest and the entire department wants to sign up, you might want to split off into smaller reading groups with narrower topics. I’ve found that between three and ten members is best for good discussion that allows everyone to participate. Choose a location that is comfortable and as far from a classroom as you can get: a more informal building on campus, a café or pub, or even someone’s living room. You’ve all done your time in the classroom, and members will be more likely to show if they don’t feel like someone’s taking attendance. Choosing a day and time when people can feel more relaxed also helps, like a late afternoon after everyone’s taught for the day while still leaving time to do some writing or grading later that night.

There are a number of ways to decide what the group will read. In some reading groups I’ve joined, a group leader knows the most about the topic and just chooses all the readings. If you don’t like a particular reading, you don’t have to show up that day. There are also more diplomatic ways. In my group, I usually ask for suggestions, make a survey of all the responses, and let the group vote on what they want to read. Sometimes, if someone has a text they’re particularly excited or knowledgeable about, he or she can lead that meeting. For the most part, though, discussion seems to run itself, with perhaps a few back-up questions in case of awkward silences. In terms of book-length, everyone is usually pretty busy: shorter is better. Short story collections can work really well if the group chooses one or two to read together, letting members read around the rest of the book if they have the time. It also depends on cost. Department or university funding for reading groups is available at some schools, but not all.

When it comes to the meetings themselves, I really try to emphasize an informal atmosphere, as you can see. Not all groups I’ve been in have been like this, though, and there is something to be said for a structured group in the midst of unstructured diss-writing and exam-studying. Shoot for a middle ground: it’s not the neighborhood book club, but it’s not class, either (especially with so many teachers in the room). One thing that will come as no surprise is that grad students are more likely to show up to any event if there’s food and drink involved. Especially if you have a mix of M.A. and PhD. Students, this informal atmosphere can help everyone feel comfortable contributing to conversation and bring their own interests to the table. You can also do some more creative things like readings of plays/poems or looking at film alongside other texts to make meetings social while still discussing the material. Starting a reading group can help you re-connect with the other scholars in your department, inadvertently bringing out the many different types of reading and discussion that can often be forgotten when you’re doing independent work… while, at the same time, having fun and relaxing with good books, good food, and good people.

Notes from the Undertow: Transatlantic Studies Reading Group Inaugural Meeting

According to the OED, undertow can be traced back to the early nineteenth century. Sporting Magazine (1817) refers to “A current,… at times counteracted by means of a strong opposing ‘undertow,’ as it is called.” If this first phrase touches upon the register of physical operations, the next lies close to that of myth and (ominous?) portent: “The recoil of the sea, and what is called by sailors the undertow, carried him back again.” The first example identifies a general dynamic of fluid directionality, describes strong flows and pulls, and suggests inconsistent, unstable forces. The second describes a geographic, biotic entity (the sea) grown quasi-monstrous, recoiling, carrying sailors “back again,” but how far? To where?

Formulating a transatlantic studies reading group at the University of Colorado at Boulder shared much with my childhood bouts with the Pacific, especially those times when the water won. Calling oneself a romanticist stakes out a somewhat reasonable or at least recognizable critical terrain. But epistemologically stepping into the oceans and seas to orient one’s work around aqueous and landed flows immediately leads one to the potentially hazardous and/or freeing problematics of how far to go and most importantly, to where—to what critical end?

When the undertow takes down even the strongest of swimmers, it’s just as disorienting and humbling as the above sentences from the OED suggest. Being sucked beneath the surface aptly parallels the problems I faced (and cannot conquer) in establishing a forum for exploring the current state of transatlantic, circumatlantic and hemispheric studies. How far back or forward in time should the readings go? What if the group’s reading selections only come from what qualifies as either British sources or literature attributed to the United States, and so the group navigates itself to the much-maligned realm of trans-national literary studies? To be completely honest, the most muddled and pressing point for me personally, is why, and if, I should be engaging in such methodological pursuits as a student committed first and foremost to the study of romantic literatures.

Our First Meeting:

Now having brought the group together for its inaugural meeting last Wednesday, we’ve proved that at least fifteen graduate students at Boulder are deeply or trepidatiously committed to throwing themselves into the fray. We are ready to see what considerations of the Atlantic and other bodies of water as well as other flows of bodies, organisms, ideas and objects will do to us, and perhaps even for us, given some amount of steadfastness and willingness to thrash about methodologically for the year. We read Melville’s Benito Cereno as our initial primary text and an article by Amanda Claybaugh on Dickens’ American book tours, which analyzes intersections between social reform and transatlantic reprinting/plagiarizing prior to the 1891 transatlantic copyright law that forbade such intellectual borrowing and trading.

For two hours we discussed things colonial, national, material, theoretical, and narratological—and speaking as just one of those who agreed to getting more than her feet wet, it was just as difficult and rewarding as getting lost in pull of the undertow while still being able, finally, to come back up for air, and for more. Next month, we’ll be making one of our great moves back in time, shifting away from the space of the slave ship and the triangular trade to discuss Locke’s Two Treatises on Government and an article by the well-known scholar of transatlantic and Native American scholarship, Kate Flint. We will close out the semester with a turn to the spaces of the Caribbean, reading the anonymously published The Woman of Colour, and will consider Elisa Tamarkin’s critical work on “Black Anglophilia.” Perhaps at its best, it would appear that these more geographically-sensitive modes of analyses might help us to engage “currents,… at times counteracted,” but that might otherwise be easy to ignore, and thus most simply reminds us to perform due diligence. Onward, to the next recoil.