Last night I had the pleasure of attending a lecture by Dr. Catherine Belling (associate professor at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine), an event launching the “Imagining Health Project” series by the IHR Medical Humanities Initiative at ASU. This series is meant to integrate art and the humanities with medicine driven by the philosophy “health is a basic human need” that encapsulates a variety of physical and mental components.

Belling’s talk, entitled “Imagining Disease–Horror and Health in Medicine,” was hosted by the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale. While I have personally been to lectures taking place in art museums, cafes, and libraries, attending a humanities-driven event at a working medical treatment and research facility was definitely a novelty. Tackling the themes of uncertainty and fear at the center of medical care, Belling’s lecture focused on what she termed “a poetics of medicine” in which the humanities offers ways to approach healthcare in all of its facets. She named three terms implicit in this discussion: imagining (or imagination), disease, and horror. I found her definitions and conclusions regarding imagining and horror to be the most compelling, and I will briefly summarize her key points below while also noting my own reactions to the material, posing questions I still need answered (perhaps you dear reader, can help!). Continue reading “"Horror in Medicine" – a Response”

The Dream of Art in Batman

“Thou art a dreaming thing, / A fever of thyself” – Keats

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sQn-vulThcY

Jack Nicholson’s the Joker is the Romantic Visionary artist in extreme. His version of the apocalypse emerges from his diabolical imagination and his scheme to poison Gotham’s commercialized vanity. This is, to recall a quote I used in a previous post, the Romantic Vision on steroids: Continue reading “The Dream of Art in Batman”

Graphic Learning: Examples of Well-Researched Comics

It seems pointless to argue that graphic novels have an important place in literature at this point. Personally, I took two classes during my undergraduate career that incorporated such texts (including Satrapi’s Persepolis and Bechdel’s Fun Home), but more often than not this is a rare occurrence and something I did not encounter in my graduate coursework. Graphic novels often do not get the attention they deserve, in part because many deem them déclassé due to their graphic nature and/or subject material, but also because they are hard to teach. While graphic novels can be analyzed through literary theory (and should be), the format itself, and most notably, the visual element of such narratives, are in a scholarly discipline all their own. One cannot teach, or even fully enjoy a graphic novel, without at least a bare minimum knowledge of art theory and visual composition. (Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art and Critical Approaches to Comics: Theories and Methods are good places to start.) But then again, neither of these things occupies some alien universe detached from what we as literary scholars already tackle. Continue reading “Graphic Learning: Examples of Well-Researched Comics”

'Tis the Season for Haunting: The Ghosts of Christmas Past

“‘Man of the worldly mind!” replied the Ghost, ‘Do you believe in me or not?’

“‘Man of the worldly mind!” replied the Ghost, ‘Do you believe in me or not?’

‘I do,’ said Scrooge. ‘I must. But why do spirits walk the earth, and why do they come to me?’” (Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol 1843).

Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol; A Ghost Story of Christmas has permeated each year’s cultural interpretation of the Christmas spirit, from adaptations like A Muppet Christmas Carol to commercials for the newest gadgets. It’s by far the most recognizable Christmas ghost story. Though we often think of Halloween as the most obvious time for telling ghost stories, Christmas used to hold that office. The Paris Review did an article about this tradition this month, with five recommendations for Christmas ghost stories. The days get shorter, the darkness rolls in and stays there, bringing the cold with it and inviting gatherings around the fireplace with warm drinks, warm company, but chilling tales. I recently became a ghost guide for my town’s ghost walks through its eighteenth-century historic downtown. We mostly run through October, but we’ve started to embrace the traditionally haunting winter evenings (well, not me, with my low tolerance for PA winter temps). In doing the tours, I’ve seen first-hand how the atmosphere created by a small group of people, gathered close in the darkness around flickering candlelight, can produce a belief in ghosts. And it was in this spirit that Dickens drew on a long history of communal ghost stories. Continue reading “'Tis the Season for Haunting: The Ghosts of Christmas Past”

Dissertating with a Hammer: An Idiot’s Generalizations on Scholarship and Activism

I begin with two passages that will be the epigraphs to my dissertation:

Few critics, I suppose, no matter what their political disposition, have ever been wholly blind to James’s greatest gifts, or even to the grandiose moral intention of these gifts … but by liberal critics James is traditionally put the ultimate question: of what use, of what actual political use, are his gifts and their intention? Granted that James was devoted to an extraordinary moral perceptiveness, granted, too, that moral perceptiveness has something to do with politics and the social life; of what possible practical value in our world of impending disaster can James’s work be? And James’s style, his characters, his subjects, and even his own social origin and the manner of his personal life are adduced to show that his work cannot endure the question.

Hero Worship, Discipleship, and the Romantic Imagination: On Spivak’s Aesthetic Education

“And so I go, asking the students to enter the 200-year-old idiomaticity of their national language in order to learn the change of mind that is involved in really making the canon change. I follow the conviction that I have always had, that we must displace our masters, rather than pretend to ignore them.” So writes Gayatri Spivak at the conclusion of a chapter entitled “The Double Bind Starts to Kick In” in her recent tome An Aesthetic Education in the Age of Globalization. Is Spivak too, I ask, such a master that we must displace if we are to abide by her own conviction? This is a question I want to pursue as I consider her treatment of British romanticism in this mammoth work. Continue reading “Hero Worship, Discipleship, and the Romantic Imagination: On Spivak’s Aesthetic Education”

Thoughts on Teaching Jane Austen

I am currently teaching a class with the very long title The Modern Self in the World: Literature and Art across Modernity, from Donne and Dürer to Baldwin and Cool Hand Luke. As with my other class (on American literature), I’ve used my teaching opportunities as a graduate student to escape the burden of academic and professional decorum. My classes, in other words, might be retitled, “books I like to read, want to read, and think you should read.” They are not lectures or surveys, but rather reading groups where my students and I try and make sense of the various texts we confront. Continue reading “Thoughts on Teaching Jane Austen”

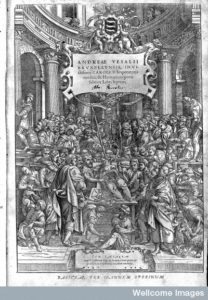

The Body on Display: A Day at the NYAM Medical History Festival

Late eighteenth century physicians (for the most part) increasingly  embraced the wisdom of learning anatomy directly from a dissected corpse. Feeling the textures and depths of the body’s interior and seeing it all firsthand became an invaluable tool for beginning physicians. However, this method of teaching ultimately relied on the advancements in medical thought demonstrated in the sixteenth century by one man: Andreas Vesalius. The brief version of his contribution to this field is that he turned a system in which the physician dictated dissection from a space removed from the actual body, and a surgeon performed what he was told on the body. Physicians, in this system, rarely encountered the actual interior of the body. Vesalius changed all that. Not only did he dissect his own corpses, but, by doing so, he corrected many of the errors in previous anatomical texts based on an assumed closeness between human and animal anatomies. His most famous work is the beautiful, fully illustrated De Humani Corporis Fabrica (often referred to as just the Fabrica). You probably recognize the frontispiece pictured here. Continue reading “The Body on Display: A Day at the NYAM Medical History Festival”

embraced the wisdom of learning anatomy directly from a dissected corpse. Feeling the textures and depths of the body’s interior and seeing it all firsthand became an invaluable tool for beginning physicians. However, this method of teaching ultimately relied on the advancements in medical thought demonstrated in the sixteenth century by one man: Andreas Vesalius. The brief version of his contribution to this field is that he turned a system in which the physician dictated dissection from a space removed from the actual body, and a surgeon performed what he was told on the body. Physicians, in this system, rarely encountered the actual interior of the body. Vesalius changed all that. Not only did he dissect his own corpses, but, by doing so, he corrected many of the errors in previous anatomical texts based on an assumed closeness between human and animal anatomies. His most famous work is the beautiful, fully illustrated De Humani Corporis Fabrica (often referred to as just the Fabrica). You probably recognize the frontispiece pictured here. Continue reading “The Body on Display: A Day at the NYAM Medical History Festival”

Experience: I Served in the British Army of 1812

My introduction to the geopolitics of British Romanticism came about in a highly unusual way. In the summer of 2007, I had a job as a historical reenactor: six days a week, I became a foot soldier and musician in a Drum Corps of the British Army during the War of 1812. My one-time service for the honour of the Prince Regent took place at Fort York, a National Historic Site located in downtown Toronto, Canada, and in this post I will share my lived observations of what the daily experiences of colonial military service would have been like for a British soldier at the height of the Romantic period. Continue reading “Experience: I Served in the British Army of 1812”

Rethinking Romantic Media: Print Alternatives

While my research has thus far focused on Romantic print media, my recent foray into the world of media archeology has led me to search for alternative media that print obscures. In Gramaphone, Film, Typewriter, Friedrich Kittler confronts “the historian’s writing monopoly” (6) by arguing that print cannot adequately take into account oral and visual culture. Writing merely stores the “facts of its authorization” (7), while “whatever else was going on dropped through the filter of letters and ideograms” (6). Kittler points to photography and film as storage media that put an end to the monopoly of print by recording the images and noise that print filters out. And yet, for scholars like ourselves interested in the period that preceded these inventions, how do we uncover the alternative media that print obscures? In order to answer this question, I turn to two examples of performance-based media that much recent work has attempted to reconstruct: lecture and drama.

Reconstructing the Romantic lecture

On February 28, 2014, the University of Colorado at Boulder hosted “Orating Romanticism,” a series of speakers that included Dr. Sarah Zimmerman of Fordham University, Dr. Sean Franzel of the University of Missouri, and CU Boulder’s own Kurtis Hessel. While each speaker focused on a particular lecturer or series of lectures, all spoke about the challenges they face when attempting to reconstruct a medium that is inherently performative and ephemeral. Dr. Zimmerman explained that Romantic lectures were critical oral arguments shaped by participating auditors as much as speakers themselves. For example, when giving a series of lectures on Shakespeare’s characters at the Royal Institution, Coleridge frequently deviated from his notes and occasionally strayed so far from the advertised topic that auditors complained in their reviews. Other lecturers changed their topics according to the audience’s immediate responses, collapsing the time between composition and reception that characterizes print. Working with such a medium proves challenging, explained Zimmerman, because the lecture’s “authoritative text,” if such a thing exists, “lies at the midpoint that marks the exchange between performer and audience.” As an inherently performative media dependent on time, place, and audience, the Romantic lecture cannot be adequately expressed in print.

Facing this challenge in his work on Coleridge’s, Hazlitt’s, and Humphry Davy’s respective lectures, Kurtis Hessel explained that in order to reconstruct these events we’re forced to cobble together “texts” from various sources, including the speaker’s notes, advertisements, reviews, and writings of those who attended. And yet, cautioned Hessel, these sources are often unreliable indicators of what actually took place. Just because a lecture was advertised, for example, does not mean it was actually held. If ticket sales failed to reach certain quotas, the event was canceled. In addition, while some lecturers like Hazlitt published write-ups of their lectures following the event, the printed version does not necessarily provide an accurate account of the lecture itself. Although it’s tempting to treat lectures in the same way we treat texts, Hessel struggles against this inclination in his work. Rather than relying on an available text, he explained, we’re forced to construct one. While print continues to dominate our understanding of Romantic-era oral media, we should seek out as many diverse sources as possible in order to reconstruct these moments. The lecture itself exists somewhere in between.

Reconstructing drama and pantomime

Drama is a similarly performative medium that presents methodological challenges when reconstructing it in print. With the exception of closet dramas and other plays that were not intended for the stage, the majority of popular stage productions were written with performance in mind. Although we have scripts, stage directions, and other textual remnants of these works, it’s difficult to imagine what occurred at individual performances. In Coleridge’s highly successful drama Remorse (1813), for example, we know that audiences were enthralled by a spectacular incantation scene in which an altar goes up in flames to reveal a painting of the protagonist’s assassination. Yet no surviving versions of the text give any indication of how this effect was achieved. Instead, our best guess comes from a write-up in The Examiner that describes “the altar flaming in the distance, the solemn invocation, the pealing music of the mystic song,” that together produced “a combination so awful, as nearly to over-power reality, and make one half believe the enchantment which delighted our senses.” Though lacking in specifics, this description depicts the scene better than the play’s stage directions, which simply read “The incense on the altar takes fire suddenly, and an illuminated picture of Alvar’s assassination is discovered.” In cases where stage spectacle played an important role in a production, paratextual materials are often better approximations of performance than the text itself.

These materials become even more important in the reconstruction of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century pantomime, a form characterized by on-stage action rather than dialogue. When trying to reconstruct the text of Harlequin and Humpo (1812) for The Broadview Anthology of Romantic Drama, Jeffrey Cox and Michael Gamer used manuscripts with short descriptions of scenes alongside audience programs and other detailed information, but it’s impossible to arrive at an “ideal text” when a performance has no words. In places where the manuscript had little detail, they looked for descriptions in newspaper reviews. One review reveals that an Indian boy performed impressive contortions and acrobatics for a good portion of Scene V, a sequence that isn’t mentioned in the manuscript and seems have been a last minute addition to the show. It’s the piecing together of these sources that gives us the closest possible approximation of the work.

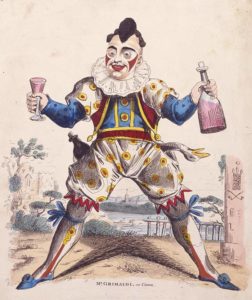

- Joseph Grimaldi as “Clown,” an archetypal character in pantomime, c. 1810. (Wikipedia)

Destabilizing print

Despite my desire to uncover alternatives to print media, to deconstruct Kittler’s “writing monopoly,” it’s obvious that print is all that remains of Romantic performance culture. And yet, in our efforts to cobble together “texts” of these lectures and plays, it becomes harder to uphold traditional notions of textual stability. Especially in instances where there are multiple versions with significant differences, books are characterized by variation, difference, and inconsistency rather than grand solidity and authority. While publishers tend to smooth over these ruptures in “definitive editions” of canonical texts, reconstructions of forms like lecture and drama refuse to lull the reader into a fall sense of continuity. The search for Romantic print alternatives, though perhaps futile, may lead us to a more nuanced understanding of the different forces at play within printed texts.