My introduction to the geopolitics of British Romanticism came about in a highly unusual way. In the summer of 2007, I had a job as a historical reenactor: six days a week, I became a foot soldier and musician in a Drum Corps of the British Army during the War of 1812. My one-time service for the honour of the Prince Regent took place at Fort York, a National Historic Site located in downtown Toronto, Canada, and in this post I will share my lived observations of what the daily experiences of colonial military service would have been like for a British soldier at the height of the Romantic period. Continue reading “Experience: I Served in the British Army of 1812”

Academic Writing & Emotigifs

We’ve all seen them.

Animated gif images, image macros, and memes on academic writing. You know the ones, like this:

“When a friend asks how the dissertation is going”

Or, similarly,

“When someone asks you how the diss is going”

There are even those created for inspiration, such as the “Shouldn’t You Be Writing?” meme.

Whether we admit it or not,

Even something as simple as finalizing a topic for this blog post, trying to decide on something that would benefit this community, was an enormous task. While I knew I wanted to discuss writing, that’s still a very broad topic. Should I write on the differences between writing to be read silently, such as for a journal article, or aloud, like a conference paper? What about whether we should include digital writing (ex. tweets, blog posts) on our curricula vitae? Tips on learning to write new genres like proposal abstracts and statements of philosophy? Is it okay to tweet about conference presentations? What about my own lessons in writing from that initial graduate course on “Writing for Publication,” to the various workshops I’ve attended and organized on writing for publication? How about the costs of writing perfectionism? Soon I realized that all of these topics share a common theme: struggling with the writing process itself.

Writing about the writing process also meant I could throw a mini gif party with all these writing related image macros and animated gifs I’ve been accumulating on Pinterest. Because let’s face it, these little animated gifs convey a strong, multimodal rhetorical message. Scholars who study the linguistics of internet language have argued that emotigifs, hashtags, “Tumblr speak,” doge speak, etc. are all powerful language tools that help us communicate in more complex and nuanced ways than simple text or emoticons can. In the case of the academic writing genre of emotigifs, they express – in a highly creative and immediate way – that academic writing requires wrangling thought and idea into words on a screen (or page, if you prefer) that, with a great deal of work, combine into a persuasive and engaging argument. As Kerry Ann Rockquemore wrote in her article “Writing and Procrastination,” “The truth is that the road from the spark of a new idea to the submission of an article, grant proposal, or book manuscript is a long and winding path.

We get distracted

“The sort of progress I make on my paper when I read Buzzfeed instead”

We get frustrated:

Then there are the times “when we think we’ve finally trouble-shooted the essay”

but then need to go back to the drawing board.

And those (hopefully rare) occasions when we worry about

But despite all the frustration depicted above, it’s not all bad. In fact, there are some days when we just want to cry out

And remember “that thing you’re writing is awesome.” Tom Hiddleston said so.

Monica Boyd

19th Century Colloquium

Arizona State University

Running the Comprehensive Exams Gauntlet: A Hopeful How-To

I have spent the last nine months thinking about my Ph.D. comprehensive examinations, and, as of tomorrow, I am nine weeks away from THE day. Yikes! And since in my current stage of borderline freak out I can think of nothing else, I have decided to write a very practical how-to/how-not-to guide for comprehensive exam preparation. Please learn from my colleagues’ and my experience and mistakes. And PLEASE add your own suggestions in the comments below. We grad students need each other’s support. I still have nine weeks, oh wise ones. I welcome your advice and in return I give you mine.

To begin, let me describe the two comprehensive exam models I know from my Masters and Ph.D. universities. Both universities position these exams as the transition between coursework and the dissertation. At each university, students are tested over a group of lists specific to their areas of study, including primary texts of all genres and critical texts. At my Masters university the exams were written. Students prepared for the exams for an average of one and a half to two semesters. The exam itself required students to write three 20+ page papers in response to the questions written by their committee (I believe the students have 4-5 questions from which they choose three). You had 48 hours in which to complete the essays. This style requires very organized and diligent note-taking, and communication with your committee members about types of questions to expect. From here, you can begin drafting potential arguments to use during the exam days.

At my current university, the exams are oral. Three hours in a conference room at the mercy of five committee members. I’m reassured by my committee that the three hour exam is not so foreboding, but for dramatic effect and to garner your sympathy, I present it as an academic gauntlet. Four committee members are (roughly) in your area of study, and one committee member is recruited from a different department to ensure fair treatment and assessment of the tester. See? A gauntlet.

Students are to master three lists of texts (each of which is approximately three syllabi-worth of material) that cover our time period, an adjacent time period, and a list of our choosing (often a dissertation list, an author list, a genre list, or a theory list). We are given three semesters in which to do this, but most students take only two. My lists cover the long nineteenth-century with a decided focus on poetry and critical prose (though I do include novels as well). I have a Romanticism list, a Victorian list, and a dissertation list, titled “Keats and the Cockney School.” These lists are self-created with the help of your committee. They must be approved, and you must provide rationales for them in the form of a 25 page document.

I did not get off to the best start in my studies. (Shhh! Don’t tell my committee!). But after consulting with friends who had run the gauntlet and lived to tell about it, I developed a reading schedule, a realistic outlook on the process, and even an appreciation for this phase in my academic career.

So here’s a taste of what I have learned over the last few months:

Continue reading “Running the Comprehensive Exams Gauntlet: A Hopeful How-To”

Why You Should Always Submit Proposals: My Surprising Experience at my First Conference

As a second year graduate student this past fall, I found myself headed to the International Conference of Romanticism at Oakland University with few goals other than to make it through my panel without throwing up, and to not look like an idiot in front of my peers. The fact that I was even in the conference was a surprise, after all I had only submitted my paper proposal just inside the deadline that summer at the encouragement of my fellow Romanticists at Arizona State. “I don’t know if I’m even ready to submit to a conference like this,” I wrote in an email responding to their reminder of the upcoming deadline. I might not have been, but with the encouragement of Kent and Kaitlin I submitted anyway, and not soon after the first surprise came—I had been accepted. Thankfully the two of them had been as well, so I figured I would have at least two people at my panel in September. As the date of the conference approached, we made the group decision to not attend the official banquet largely due to financial concerns, and believing that none of us had a chance at winning the competitive Lore Metzger Prize, which went to the best essay read by a graduate student at the conference.

Well reader, I won that prize. Instead of learning this news at the banquet where I could have stood up and been recognized for my paper “The Undead Presence: Exploring Boundaries of Life, Death and Sex in ‘Christabel,’ ‘The Skeleton Priest,’ and ‘The Aerial Chorus’” by my fellow Romantic scholars, I found out via text message from Jacob while I was at an Irish pub down the street. I was lucky enough to have Kaitlin and Kent by my side at that moment to congratulate me, but the initial shock of that moment has yet to wear off. I am so honored to have won such a prestigious award not only because I was a second-year graduate student and that it was my first Romantic conference and first out of state conference, but because I wrote about something I am truly passionate about. Talking about the importance of walking, talking corpses in Romantic literature seems risky, but it paid off.

The lessons I learned from this experience are significant, and I believe, important to share. First, if you are lucky enough to find a community in your university that encourages and supports you, listen to them. They might know of potential you do not see in yourself. I would not have even tried to be at ICR if it wasn’t for the kind (but firm!) push from Kent and Kaitlin to submit a proposal, and I would not have won the award for best graduate paper without the edits and suggestions given to me by the ASU 19th Century Colloquium. Peer review is good, honest peer review with your best intentions in mind is fantastic—and absolutely integral to succeeding in the academic field. Secondly, always submit a proposal. Even if you think there is no chance in hell that you will be accepted to present at that conference, or be asked to write a chapter for that book, do it anyway. Not only is it excellent practice, but it will also force you to be more confident in your ideas and get your name out there. When you get accepted (because you undoubtedly will with all those submissions), have your work critiqued by people you trust and respect. They will tell you the truth, strengthen your argument, and you will be better for it. And finally, write about what you love. Zombies and vampires and all the variations inside and outside of those categories might be a laughable topic at first, but I truly believe that if I had gone to ICR with anything else than that, anything other than something I am passionate about to the point of insanity, I would not have won the Lore Metzger Prize. So take those risks, submit those proposals—the outcome could surprise you.

Oh, and always fork over the money and go to the banquet.

Emily Zarka

The Romantic Poets' Travel-Guide to Italy

“Thy rare gold ring of verse (the poet praised) / Linking our England to his Italy!” Thus concludes Robert Browning’s masterwork The Ring and the Book (1868-69), a poem whose composition celebrates the longstanding artistic relationship between the two nations in the nineteenth century.

English literature is full of Italian journeys. There are honeymooners, though their marriages tend not to fare well (Dorothea and Casaubon; Gwendolen and Grandcourt; George Eliot’s own Venetian wedding-night debacle). There are ill-fated convalescents (Keats; Elizabeth Barrett Browning; Milly Thrale; Ralph Touchett). There are traveloguing or scholarly visitors (Sydney Owenson; John Ruskin; Byron in his late Childe Harold phase). There are also exiles (Byron and the Shelleys). And—finally—there are Italians émigrés in England (the Rossettis).

In this post, I recommend some enjoyable and Romantically-informed travels in Italy—and invite you to contribute adventures of your own in the comments section!

Rome

Like the Romantics, you may find yourself exploring thousands of years of history with the help of a guidebook – perhaps Italy, written by Sydney Owenson (Lady Morgan) in 1821. You might also consult Byron’s always entertaining prose. He wrote in 1817, “I am delighted with Rome—as I would be with a bandbox, that is, it is a fine thing to see, finer than Greece; but I have not been here long enough to affect it as a residence. [I have been] about the city, and in the city: all for which—vide Guide-book.”

But, apparently unsatisfied with the “Guide-book” in question, Byron developed his own vision of Rome in the fourth Canto of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, where he writes (with characteristic grandeur):

Rome—Rome imperial, bows her to the storm,

In the same dust and blackness, and we pass

The skeleton of her Titanic form,

Wrecks of another world, whose ashes still are warm. (IV. 46)

and

Oh Rome! my country! city of the soul!

The orphans of the heart must turn to thee,

Lone mother of dead empires! and control

In their shut breasts their petty misery. (IV. 78)

Rome admired Byron back, and it comes as no surprise that the poet is omnipresent in the city. In the Villa Borghese, for instance, look for the Byron statue at the entrance to the park. This is a copy of the famous Thorvaldsen bust of the poet, for which he posed in Rome in 1817 (the original statue, refused by Westminster Abbey, is at Trinity College, Cambridge).

Even classical sites like the Colosseum can be seen anew through a Byronic lens. The poet devotes six stanzas to the gladiatorial games that took place in that “enormous skeleton” in Childe Harold, Canto IV, and finishes with this epic misquotation of the Venerable Bede:

“While stands the Coliseum, Rome shall stand;

When falls the Coliseum, Rome shall fall;

And when Rome falls—the World.” (145)

Nearby, Trajan’s Column, now separated from the Colosseum and the Roman Forum by a Mussolini-era expressway, also gets the sublime Byronic treatment: “Whose arch or pillar meets me in the face, / Titus or Trajan’s? No—’tis that of Time…” (Childe Harold IV. 110).

Byron began writing Canto IV—the Italian leg of his peripatetic long poem—in 1817, at his Roman residence, Piazza di Spagna 66, which is located at the bottom of the famous Spanish Steps. The building now seems to be a dentist’s office—suitably befitting its red-tooth-powder-obsessed former resident.

Considerably more important, however, is Piazza di Spagna 26, a pink building across the square and directly next to the steps. This is now the Keats-Shelley House. Keats died here in 1821, and the building has since been converted into a museum celebrating the life and works of the second-generation Romantic poets, especially Keats.

The poet’s modest rooms, on the second floor, are particularly moving: on the wall is a brass plaque that commemorates his death, and the bedroom has been restored to its historical condition, including the original fireplace and period furniture. The museum displays many of Keats’s belongings and letters, and even his death-mask.

The Keats-Shelley House also boasts an excellent collection of over eight thousand volumes related to Romanticism, including many early editions, as well as plentiful (and sometimes disturbing) paraphernalia associated with the English poets. There are many well-preserved original letters in Mary Shelley’s hand. Look out for locks of hair belonging to Milton and the Brownings, and scraps from Byron’s red bed-curtains (dating to the night terrors he experienced during his marriage). Perhaps most uncanny is Byron’s wax mask, which he wore during the Carnival at Venice. You can even take a virtual tour of the Salone (the central room) without the cost of airfare to Rome.

Shelley’s impassioned response to Keats’s death in “Adonais” (1821) leads us to our final Romantic site in Rome. “Go thou to Rome,” Shelley urges, to see the “slope of green access / Where, like an infant’s smile, over the dead / A light of laughing flowers along the grass is spread” (433, 439-41)—that is, to the Protestant Cemetery, where not only Keats, but also Shelley’s son William (and ultimately Shelley himself) were buried. Other notable Romantics there include Keats’s friend Joseph Severn, and Shelley and Byron’s friend Edward Trelawny. Keats’s grave famously features only the inscription “Here Lies One Whose Name Was Writ in Water.” The map of the cemetery is available here.

Florence

Florence is known for its unparalleled art galleries, which were celebrated even in the time of the Romantics. Indeed, Byron’s letters attest to how little the collections have changed in two centuries:

“At Florence I remained but a day, having a hurry for Rome, to which I am thus far advanced. However, I went to the two galleries, from which one returns drunk with beauty. The Venus [dei Medici] is more for admiration than love; but there are sculpture and painting, which for the first time at all gave me an idea of what people mean by their cant, and what Mr. Braham calls “entusimusy” [enthusiasm] about those two most artificial of the arts. What struck me most were, the mistress of Raphael, a portrait; the mistress of Titian, a portrait; a Venus of Titian in the Medici gallery—the Venus; Canova’s Venus also in the other gallery: Titian’s mistress is also in the other gallery (that is, in the Pitti Palace gallery); the Parcae of Michael Angelo, a picture; and the Antinous—the Alexander—and one or two not very decent groups in marble; the Genius of Death, a sleeping figure, etc., etc.”

“The Venus” (Byron’s eyebrows clearly raised) likely refers to the celebrated and controversial “Venus of Urbino,” which is still displayed in the Uffizi Gallery. The other portrait of “Titian’s mistress,” which the poet saw in the Pitti Palace (the former residence of the Medici family), has a particularly interesting history. Usually titled “La Bella,” this painting of an unknown woman (probably the same model used for the “Venus of Urbino”) was taken to France in 1800 during Napoleon’s conquest of Florence. (Napoleon briefly occupied the Pitti Palace itself, and his opulent bathrooms, which are still accessible to visitors, would likely have provided Byron with considerable entertainment). The painting was returned to Florence fifteen years later—only two years before the poet visited the Pitti Palace in 1817. When I visited the gallery in 2011, “La Bella” had just undergone an in-depth restoration, the details of which were explained in an extensive exhibit.

Today, the Pitti Palace also features Lorenzo Bartolini’s bust of Byron, for which the poet posed some years after his sitting with Thorvaldsen:

Byron’s mistress, Teresa Guiccioli, offers an amusing account of the sculptor’s encounter with the poet:

“Bartolini, the sculptor, wrote to Lord Byron to ask permission to come to Pisa and carve a bust of him. Lord Byron liked very much to be surrounded by portraits of his friends and those whom he loved—but he was loath to pose himself. When he did , it was always to please friends. Thorwaldsen had sculptured his head and shoulders for Hobhouse, but Lord Byron did not even have a plaster cast. ‘It’s all very well,’ he said, ‘getting painted’ […] But to pose for a bust in marble struck him as vanity and pretentiousness, as wanting to obtrude oneself on posterity rather than leaving a private memento. […] When pressed, he replied that he would sit, provided it was not for himself, and that Bartolini would commit himself to doing a bust of Countess Guiccioli at the same time.

When [Bartolini] set eyes on Lord Byron, he announced that he could never do justice to such an original, since Lord Byron’s handsome appearance and his expression seemed to him to exceed the power of art. He was quite right […] His beauty was wellnigh superhuman in its manifestation, and Bartolini was far from being the man to overcome the difficulty.

Lord Byron himself […] was unfavorably impressed; and when the marble was destined for Murray, he wrote to him: ‘The bust does not turn out a good one, though it may be like for aught I know, as it exactly resembles a superannuated Jesuit.’ Then again: ‘I assure you Bartolini’s is dreadful.’ He also added that if it were like him, he could not be long for this world, for the bust made him look seventy.”

I leave Bartolini’s likeness to your judgment, though the partner bust of the Countess Guiccioli (normally held at the Istituzione Biblioteca Classense in Ravenna) strikes me as being quite serene and beautiful. And a reading of Browning’s “The Statue and the Bust” would not be amiss when visiting the Pitti Palace.

Next, though not the grandest cathedral in Florence, the Basilica di Santa Croce is a fascinating historical site, and it too gets the Childe Harold treatment:

In Santa Croce’s holy precincts lie

Ashes which make it holier, dust which is

Even in itself an immortality,

Though there were nothing save the past, and this,

The particle of those sublimities

Which have relaps’d to chaos:—here repose

Angelo’s, Alfieri’s bones, and his,

The starry Galileo, with his woes;

Here Machiavelli’s earth, return’d to whence it rose.

These are four minds, which, like the elements,

Might furnish forth creation: —Italy! (IV. 54-55)

Though Harold was rhapsodically transported by the four great monuments within Santa Croce, Byron himself was less impressed: “The church of ‘Santa Croce’ contains much illustrious nothing. The tombs of Machiavelli, Michael Angelo, Galileo Galilei, and Alfieri, make it the Westminster Abbey of Italy. I did not admire any of these tombs—beyond their contents. That of Alfieri is heavy, and all of them seem to me overloaded. What is necessary but a bust and a name? and perhaps a date?” But in spite of Byron’s derision, Donatello’s frescoes are worth seeing, and more recent additions include a statue by Henry Moore and a monument to Florence Nightingale on the cathedral grounds.

Moving forward through the nineteenth century, a literary tour of Florence would be incomplete without a visit to Casa Guidi, where the Brownings lived from 1847 to Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s death in 1861. Casa Guidi is located on the piano nobile (second floor) at Piazza San Felice 8. Now owned by Eton College, the home has been restored as a museum. Look out for the Brownings’ personal collection of flea-market-acquired Renaissance art.

And, in true Browning spirit, when you visit one of Florence’s many street markets, bring along your copy of the Old Yellow Book, which Robert Browning bought at a Florentine market in 1860. The poet ultimately used the book’s voluminous correspondence about a 1698 murder case to develop his best-selling poem, The Ring and the Book.

La Spezia and the Bay of the Poets

A lovely day-trip from Florence will take you to the province of La Spezia in Liguria, located next to the Tuscan border. The area is most famous for the Cinque Terre, a collection of five tiny coastal villages now designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which are linked by a train and hiking trails. The stretch between La Spezia proper and Lerici, one of the many small towns in the area, has been renamed the Golfo dei Poeti (the Bay of the Poets) after the Shelleys and Byron, who lived in the area. The Shelleys’ home on the beach of San Terenzo, Casa Magni, now renamed the Villa Shelley, is accessible by coastal road. The villa is actually available for private rental, though the damage deposit alone might prove too much for a graduate student’s stipend… There is also a monument to Shelley in nearby Viareggio, where Shelley was cremated.

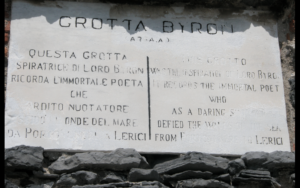

Portovenere, another UNESCO-protected village on the Ligurian coast, pays considerable homage to Byron. Most important is the Byron Grotto, which commemorates the “Immortal Poet, who as a Daring Swimmer Defied the Waters of the Sea” by swimming from Portovenere to the Shelleys’ home at Lerici.

The grotto isn’t a particularly appealing swimming-hole, as it’s filled with sharp rocks (perhaps of interest to Romantic geologists!), but there is a staircase that will take you near the water’s edge. Local shops and pizzerias are also named in memory of Byron. And be sure to sample some of the locally made pesto (the town holds a Feast of the Basil every year).

Venice

To set the tone for your final stop, begin by reading Byron’s letters and journals from 1817-1818. A sample: “I am just come out from an hour’s swim in the Adriatic; and I write to you with a black-eyed Venetian girl before me, reading Boccaccio…” Poetically, his first attempt at ottava rima, Beppo, is absolutely required reading for a Venetian stay.

There are a few key literary stops. First is the Palazzo Mocenigo, which Byron rented from the Mocenigo family in 1818. The palace has been turned into a museum of textiles, and much of the décor on the piano nobile dates back to the eighteenth century. The palazzo’s library holds extensive collections of early editions, including literary works by Byron and the Gambas (Teresa Guiccioli’s family of origin).

But be warned: there are several Mocenigo palaces in Venice. This museum is in the San Stae district. When I visited in 2011, museum staff told me that Byron lived on the piano nobile of that building; unfortunately, subsequent searches suggest that the poet lived in another Mocenigo palace in the San Marco district, which I can confirm is closed to the public. But you can see the San Marco Mocenigo palace from a #1 vaporetto ride on the Grand Canal, and admire the balcony from which Margarita Cogni took her impassioned dive during a domestic squabble with the poet.

More rewarding for the poetically-inclined is the Brownings’ palazzo, Ca’Rezzonico, which is located on the Grand Canal and has its own water-taxi stop. Bought by Pen Browning, the poets’ son, and his heiress wife, this was Robert Browning’s last residence. Like the Palazzo Mocenigo, Ca’Rezzonico has also been converted into a museum dedicated to eighteenth-century Venice. It boasts a recreated apothecary’s shop on one of the upper floors, and a traditional enclosed gondola, “Just like a coffin clapt in a canoe” (Beppo ll. 150-51), in the main entrance. (And, as Shelley’s heroic couplets in “Julian and Maddalo” make clear, “gondola” really did rhyme with “way” in the nineteenth century). Browning’s rooms are on the ground floor; when I visited, they were closed for repairs. The museum café is lovely, though, and you can sit on the terrace overlooking the canal.

Located in the city centre, St Mark’s Square, is the Palazzo Ducale (Doge’s Palace), the historical residence of the democratically-elected rulers of Venice, and its annexed prison. Notably for Romanticists, the Doge’s Palace features the so-called Bridge of Sighs, a name fancifully coined by Byron to commemorate the sighs of the prisoners as they caught a final glimpse of the lagoon before being taken to their cells. As usual, Childe Harold says it best:

I stood in Venice on the Bridge of Sighs,

A palace and a prison on each hand;

I saw from out the wave her structures rise

As from the stroke of the enchanter’s wand:

A thousand years their cloudy wings expand

Around me, and a dying Glory smiles

O’er the far times, when many a subject land

Look’d to the wingèd Lion’s marble piles,

Where Venice sate in state, throned on her hundred isles! (IV.1)

And, for eighteenth-century aficionados, the Doge’s Palace offers a splendid tour focused on Casanova’s imprisonment and dramatic flight from the allegedly “unescapable” prison.

My final suggestion, for those looking to emulate Casanova’s escape from Venice’s main tourist hub, is a short boat-journey to the Lido, the final stop on the #1 vaporetto line. Here, you can revisit the initial setting of Shelley’s conversation poem “Julian and Maddalo,” which was based on a series of philosophical debates he had with Byron in Venice in 1818. The “bank of land which breaks the flow / Of Adria towards Venice” was a favourite riding-place for the poets: “This ride was my delight.—I love all waste / And solitary places” (ll. 2, 14-15). And, looking West from the Lido at sundown, you can try to find the Maniac’s dwelling:

A building on an island; such a one

As age to age might add, for uses vile,

A windowless, deformed and dreary pile;

And on the top an open tower, where hung

A bell, which in the radiance swayed and swung… (99-103)

One final word of caution: take care not to travel to the Lido in a “heavy squall,” lest you, like Byron, return to an unexpected dressing-down: “Ah! Dog of the Virgin, is this a time to go to the Lido?”

Happy travels—and may you, like the poets, be creatively inspired by Italy—the “Mother of Arts, once our guardian, and still our guide” (Childe Harold IV. 47).

(All photos belong to Arden Hegele)

"I have a new leaf to turn over:" A Romanticist's Resolutions for 2014

I think we can all agree that Keats’s Endymion (1818) was a critical and commercial failure. As Renee discusses in her post, Tory reviewers lambasted the poem because of Keats’s affiliation with outspoken radical Leigh Hunt. Although the poem’s most notorious critic, John Gibson Lockhart, notes its metrical deviations from the traditional heroic couplet form, he spends more time attacking Keats personally: “He is only a boy of pretty abilities, which he has done every thing in his power to spoil.” It’s no wonder, then, that Keats’s letters written in the months that followed show a recurring preoccupation with self-improvement, or “turning over a new leaf.” In a short letter to Richard Woodhouse (friend and editor) dated December 18, 1818, he writes “Look here, Woodhouse – I have a new leaf to turn over: I must work; I must read; I must write.” He’d repeat the phrase again that April in a letter to his sister, complaining that he had “written nothing and almost read nothing – but I must turn over a new leaf.”

Due to my unfortunate tendency to self-identify with whomever I’m reading (“OMG, Keats, I know EXACTLY what it’s like to have your work rejected and then mooch off your friends because you have no money. WE ARE THE SAME PERSON.”), Keats’s desire to “turn over a new leaf” resonates as I prepare for a new semester of graduate school in the new year. While our situations are slightly different – constructive criticism of a seminar paper not quite as devastating as the complete and utter failure of a published book – his mantra for self-improvement sounds eerily like that of a graduate student: “I must work; I must read; I must write.” In the spirit of turning over a new leaf, and hopefully transforming that Endymion-esque seminar paper into a Lamia, I present to you my academic resolutions for 2014. I should note that many of these will be obvious to the more seasoned scholars among you, but for all of you newer grads out there, I hope you’ll find my mistakes instructive.

Resolution #1: I will develop arguments from texts instead of making texts conform to my arguments.

This one seems easy in theory, but it’s something I’ve been struggling with throughout the semester. I’ll read one text – Endymion, let’s say – and then a bunch of criticism, and its reviews, letters, etc. Then, I’ll develop an idea about how Keats’s later poems revisit the same genre and politics as Endymion, but ultimately rewrite them. Except, I’ll form this connection even before I’ve read the later poems, just because it sounds so smart and will make such a good paper. Then, I’ll set about writing the paper and finally get around to reading Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and other poems (1820), and only then will I realize that the texts interact in completely different ways than I had originally thought. Of course, there’s not enough time to completely rewrite my paper, so I stick with the argument, praying that the reader doesn’t realize I made this crucial error.

So, simply put, I resolve to stop doing this faulty method of research. I’m going to let myself be confused by texts, and stop trying to develop beautiful, complex arguments before I’ve had time to fully read and think about them. If a brilliant idea pops into my head before I’ve done this, I’ll write it down, set it aside, and consider it later. As a wise professor once told me, “Always start with close reading. If you leave it till the end, it will always most certainly change your argument.”

Resolution #2: I will accept that I am, first and foremost, a student.

A wise man (Michael Gamer) once told a group of English majors, “graduate students are full of themselves.” I hate to say it, but I’m living proof of this. I started graduate school last August under the impression that I was a Romanticist. In my undergrad days I was merely an “aspiring Romanticist,” but starting a Ph.D. program gave me the right to crown myself with the full title. Once I was accepted, I thought that I had made the transition from student to scholar, and deceived myself into believing that I knew more about my field than I actually do. Thankfully, the enormous ego that Michael prophesied was soon deflated when I realized a few weeks into class that, in fact, I know very, very little about the period in which I claim to specialize. Of course, this realization was accompanied was a decreased sense of self-worth, doubt about whether I was in the right line of work, and a frantic conversation with my advisor in which I dramatically exclaimed, “I KNOW NOTHING!” “That’s ok,” he assured me, “you’re a student, and you’re not supposed to. Frankly, you’d be surprised how many people in the field don’t know much either.” So, for 2014, I resolve to remind myself that I’m not a scholar yet; I’m a student. I will accept the limits of my knowledge while doing my best to expand them.

Resolution #3: I will overcome writing anxiety.

This problem plagues many of us, and it’s one of my biggest areas for improvement in the new year. Sometimes, the sheer size of what I need to write, the nearness of the deadline, and difficulty of the subject matter create a Kafka-esque paralysis in which no writing is accomplished. I can tell I’m experiencing this when I go to extra lengths to avoid starting a paper, whether it’s extra research, extensive outlining, or a meticulously organized Spotify playlist entitled “Writing.” As many of us know, talking about writing and thinking about writing is not actually writing. The only way to overcome this problem is simply to write more. At the advice of many of my peers, I plan to write everyday, especially while I conduct research. There were simply too many times this year when I was tempted to end my seminar papers in the way that Milton ended “The Passion” (1620): “This Subject the Author finding to be above the years he had when he wrote it, and nothing satisfied with what was begun, left it unfinished.” I’m pretty sure only Milton could pull off that one.

Resolution #3.5: I will write my blog posts on time.

This probably should’ve been number one. Thank you, Jake and fellow NASSR grads, for your patience.

Happy 2014!

Literature Through Participation: Confessions of a Table-top RPG Player

I am 5’ 6.” I am 120 pounds. I have a scar on my left arm. I have silver hair. I am an Amazonian warrior with a halberd. My name is Trish-la.

I am 5’ 6.” I am 120 pounds. I have a scar on my left arm. I have silver hair. I am an Amazonian warrior with a halberd. My name is Trish-la.

Obviously this is not actually what I look like or who I am. My name is Deanna Stover. I have never held a halberd, let alone been any sort of warrior (although my hair is beginning to turn silver. Thank you graduate school applications). No, I play Dungeons and Dragons. What I’ve just described are the basic stats of the first character I ever developed and played. It was 2000, I was 10 years old, and I stumbled into the game because a friend’s mom ran a game for the neighborhood kids.

First of all, let me make this clear: I am no expert about D&D. I can, however, give everyone a brief background of what the game is: D&D is a table-top role playing game (RPG). It is also a game that inspired a lot of controversy and negative reactions in the 1980s. People claimed that it promoted witchcraft (how 15th- and 16th-century!) and devil-worship. Role playing games still have a negative connotation associated with them; you should see the reactions people have when they find out I play Dungeons and Dragons. There’s also very little understanding about what D&D actually is. Typically people believe it is a video game (and there are those around), but a table-top RPG is different.

A Dungeon Master (DM) develops a basic story line and the “party” (typically around four to six players in my experience) influences the way that story will work out through their own decisions, interactions with other characters, and the luck of the dice. The dice involved are not just your average 6-sided dice; the die we use most is 20-sided. D&D is very hard to understand without playing. However, as I will explain, these games may spark a particular interest in those of us who love literature.

Flash forward to 2012. I didn’t remember playing my first campaign, let alone the dusty binder where I kept my character sheet (this helps you keep track of your stats, your skills, your weapons, and any other information you may need during the game) and my accumulation of die. I didn’t remember any of this until a few friends once again introduced me to D&D. However, I fell in love all over again. In the past year, I’ve participated in three campaigns, and I am a walk-in character in a fourth. I have literally laughed and cried my way through these adventures.

So, what does this have to do with literature? Well, not only is Dungeons and Dragons inspired by literature and mythology, it involves the creation of new narratives every session. In that dusty binder from my first foray into D&D, I have these instructions: “The players are like characters in a book that you, the players, are writing with the [DM].” Playing as an adult, I am ever more aware of the truth behind this statement.

So, what does this have to do with literature? Well, not only is Dungeons and Dragons inspired by literature and mythology, it involves the creation of new narratives every session. In that dusty binder from my first foray into D&D, I have these instructions: “The players are like characters in a book that you, the players, are writing with the [DM].” Playing as an adult, I am ever more aware of the truth behind this statement.

Admittedly, the literature that inspired D&D is typically associated with the 1960s and 1970s, something that may be foreign to those of us who are interested in the 19th-century, but the connection between D&D and all literature students is still a vibrant one. I am not a creative writer, I am definitely not an actress, and I never even played video games as a child, but the attraction to this game is still strong. The communal storytelling is what makes it so appealing and, honestly, there are some elements of each campaign that reference Romantic and Victorian literature; the campaign I’m currently in has some Swiss Family Robinson-esque elements tied in. But for me the most entertaining part of D&D is feeling like I am a part of a Choose Your Own Adventure novel every time I step into the room.

Perhaps you can see this post as a recruitment for D&D or even RPGs in general, and on some level I suppose it is, but what I am really trying to point out is that, even while I spend most of my life now nose-deep in 19th-century literature and papers I have to grade, D&D is what keeps reminding me what is so magical about words. I have watched the DM create a world all his own (albeit influenced by D&D lore, Roman and Greek mythology, and even modern video games), and I have participated in its creation. In the end, D&D is just five people sitting in a room for six hours every week speaking to each other, spinning a story and interacting through words alone, but only there can I become a warrior woman or even a half-dragon. Through our simple words and a few rolls of a die, a whole new world is born—it is literature through participation.

Romantic Geologies and Post-Organic Forms

I’d like to begin by thanking the NGSC for welcoming me to this year’s blogging roster. It is a pleasure and privilege to write alongside these intriguing and diverse graduate scholars, and I’m looking forward to reading the material our collective will produce this year.

The blog posts we’ve seen already have been so compelling, both intellectually and personally, that I would like to continue the conversation by engaging with the fundamental questions previous posts have posed. “Fundamental” seems to be a key word for us, as we think about how the foundations of our scholarly temperaments act as cornerstones for our intellectual flights. As Nicole and Deven’s posts illustrate, we can describe this layered relation of the personal to the scholarly by drawing on material metaphors of sedimentation, accretion, and metamorphosis.

Deven and Nicole’s descriptions of their scholarly uses of archaeology and geology—as accretive fields that can inform their work with the material aspects of literary texts—come at a fortuitous time, for me at least. I have been thinking about how aspects of literary form can be captured through scientific metaphors, and their posts have sparked my interest in thinking about how geology and Romantic poetic form intersect.

Geology is a fascinating area within the Romantic sciences, partly due to the period’s uncertainty about whether “rocks and stones and trees” formed an organic continuum. This problem of unclear organicity dated back at least to Buffon’s 1749 proposal that mountains were formed when “all the shell-fish were raised from the bottom of the sea, and transported over the earth.” During the height of British Romanticism, the problem of distinguishing between organic and inorganic forms was compounded by the discoveries of giant fossils of extinct lizards between sedimented layers of rock. In 1809, the natural scientist Georges Cuvier, who had already examined the fossil of a giant sloth and coined the term mastodon, classified these reptilian fossils as the Mosasaurus and the Ptero-Dactyle, leading the charge for the study of dinosaurs, which was to reach a high point in the discovery of the iguanodon in the 1820s. As a geologist as well as an early paleontologist, Cuvier was faced with the challenge of defining sedimented organic forms as both crucial to, and distinguished from, non-living terrestrial matter.

This instability of Romantic geology shook the foundations of the period’s poetry. Though we might usually think of huge and ancient organic forms first emerging “to rise and on the surface die” in Tennyson’s 1830 poem “The Kraken” (l. 15), Romantic literature abounds with buried dinosaurs and geological eruptions. Keats’s Endymion witnesses skeletons “Of beast, behemoth, and leviathan [and] Of nameless monster” on the ocean floor (III, 134-36), while in Cain, Byron challenges the usual Biblical chronology by referring to the “Mighty Pre-Adamites who walk’d the earth / Of which ours is the wreck” (II.ii, 359-60). Likewise, in Prometheus Unbound, Shelley describes at length the “monstrous works and uncouth skeletons” and “anatomies of unknown winged things” that lie buried in the deep (IV. 299, 303). Moreover, geology could help describe the poetic process: we see this best in Byron’s celebrated metaphorical account of his own creative tendencies, with his passions building up internally and finally erupting volcanically into verse. (Meanwhile, in Don Juan, he jokingly writes, “I hate to hunt down a tired metaphor: / So let the often used volcano go. / Poor thing! How frequently, by me and others, / It hath been stirred up till its smoke quite smothers” [XIII.36]). At the same time, though he doesn’t acknowledge it, Romantic geology poses a problem for Coleridge’s definition of literary organic form, which considers the growth of the text from its inception to its adult shape—not its later stages of death, decay, and post-organic potential re-use.

Today, Romantic geology, with its imagery of defunct and sedimented layers of organicity, has profound implications for how we think about poetic form—particularly the forms of Romantic poetry. Geology is a key metaphor for many Romantic critics: David Simpson, for instance, writes that “a great deal of Wordsworth’s poetry is best approached as if it were a core sample of an especially contorted geological substrate. One works with a rough prediction of how the layers ought to relate one to another, but there are continual local deviations and surprises.” Moreover, in recent New Formalist arguments, the sedimentation of dead organic matter can be a crucial motif for thinking abstractly about the life-cycle of a literary form or genre. Recently, I read a very compelling essay, Group Phi’s “Doing Genre” (in New Formalisms and Literary Theory, eds. Theile and Tredennick, 2013), which takes geology, plasticity, and recycling as its governing metaphors. In this text, Group Phi proposes that “genre” is a “sedimented and metamorphic historical category that is received by readers,” and that “form” is the “the reader’s activity of adopting/adapting that category for further use”—more simply, that a genre is like a sedimentary rock, with accretions of its use built up over time, while form is like the wind, shaping the rock and depositing new layers of use upon it. Further developing this intriguing metaphor of geological sedimentation, Group Phi then discusses at length how genres can be “recycled” and “repurposed”—to my mind, invoking a layer of crude oil, the result of decayed organic matter, that is buried within the sedimented structure, drawn out, made plastic, “refocused, repurposed” and reshaped, and then recycled for future use. This is no doubt a metaphor of literary form characteristic of our own time, reflecting our concerns about the ethics of geotechnical excavation, and particularly the problem of violently appropriating formerly organic structures, now metamorphosed into inorganic matter (oil). Group Phi’s invocation of recycling, mid-way through the essay, is perhaps one way of “greening” their potentially problematic metaphor of the generic sedimentation of post-organic (literary) forms.

But the Romantics themselves may have something to say about these contemporary geological forms, and here I’m thinking of Shelley in particular. In Alastor, or the Spirit of Solitude, Shelley writes about the hero’s journey as he pursues “Nature’s most secret steps” to where the “bitumen lakes / On black bare pointed islets ever beat / With sluggish surge” (85-86). What Shelley means by “bitumen lakes” has long posed a problem for critics, who have variously identified them with the Dead Sea, with the lake of fire in Paradise Lost, or with molten lava-flows in general; the most obvious precedent for Shelley’s 1815 use of the term is Southey’s reference to the “bitumen-lake” in Thalaba the Destroyer (1801). To me, the image of bitumen lakes in Alastor points within Romanticism to the era’s own problem of uncertain organicity (compounding the animal imagery of decayed dinosaurs, “bitumen” introduces a layer of vegetable matter in its etymological relationship to “pitch”). Yet for today’s readers, Alastor‘s bitumen lakes gain much in the translation: “bitumen” is the correct scientific term to describe the heavy crude oil now being excavated—in part, through hydrofracking—from the vast tar/oil sands of Alberta. Anticipating one of the great environmental controversies of our time, Shelley’s prescient use of the geological term can perhaps cast light on the deep Romantic substrates of current forms of representation of the tar/oil sands project.

In short, building on Group Phi’s model, we might look more closely at how the geological realities that underlie our contemporary metaphors of form and representation are built upon a deeper layer of Romantic uses. The mixed organicism of geological sediment has rich potential for talking about poetic language. Recalling Shelley’s account of continually dying metaphors in A Defence of Poetry, Ralph Waldo Emerson writes that “language is fossil poetry”; we too might look to the strata of literature’s organic forms in our own search for deeper meanings within Romanticism.

Memoirs and Confessions of a Second-Year Ph.D. Student

Here are the facts as I know them: 1. There are never enough hours in a day; 2. I have students who still think I don’t know that changing their font from Times to Courier adds at least a page to their essays; 3. The long 19th century is such a joy to study.

I didn’t always know these facts. When I was an undergraduate English major, using Courier in every paper I wrote about books that I only partially read, I was aimless. I took classes in order to get my degree, I earned A’s, and I didn’t minor in anything. You could say that I wasn’t the most pragmatic person on the planet. At the time, I wasn’t fully focused on school or my future; my older brother had left for Israel instead of attending law school as he had originally planned, and I struggled, trying to understand his decision. Later, as I pondered what I might do after my B.A., I was torn between graduate school and law school. A Romanticism seminar in the fall of my senior year tipped the scales.

One of the first books that we read was Frankenstein, the first assigned book of my undergraduate career that I read cover to cover. What sold me on Mary Shelley’s work wasn’t the fact that she wrote in response to a ghost story competition—instead, it was an anecdote shared by my professor. He told us how he had inscribed the creature’s words: “I will be with you on your wedding night” in a card at his friend’s wedding. How clever, I thought. I, too, wanted to be that witty, literary friend at weddings, but I realized that I should not and could not quote a book that I had not read. It was the first time that I fell in love with a canonical work.

We read a lot of other interesting works in class, and– in case you’re wondering–I did actually read them in their entirety. However, it was the last assigned work of the semester that changed my life. But Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice didn’t grab my attention right away. So, to make it more animated, I began reading it aloud to my cats with different voices. Soon, I was invested in the characters. And then I brought my interpretation of the novel to class: I said there was an erotic attachment between Darcy and Bingley. My classmates reacted with violent disagreement. They took it personally—that is, they were uncomfortable with any reading of a famously heteronormative text that involved queer desire. In all honesty, their disagreement delighted me. It motivated me. It led me to attend office hours and read literary theory for the first time. I read Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Freud, Lauren Berlant, and Michael Warner. I wrote multiple drafts of my end-of-semester paper. And I realized that—just as my brother had done something unconventional that he loved—I loved writing about literature that I had actually read and thought about in unconventional ways; I needed to read for intellectual engagement, not just for pleasure or for finishing an assignment.

I didn’t know it then, but I had stumbled upon the subject I am most passionate about, the deconstruction of heterosexist interpretations of texts. You could say that Pride and Prejudice was my patient zero. As a MA student, I continued working with Austen; the next text that I plunged into was Persuasion, and then it was Emma. In my M.A. thesis, I argued that the heteronormative relationships depicted in Austen’s three novels are built and premised upon queer desire.

As a Ph.D. student who will enter into her final semester of coursework in January, I am actively compiling my exam lists and just as actively kicking myself for not actually reading for my first three years of college. The list of works that I’ve read, while growing, is woefully underdeveloped, and I see my exam lists as an opportunity to atone for my undergraduate sins. Even though I’ve been exposed to theory and a variety of tropes and texts, I remain interested in looking at texts—especially famous heteronormative love stories—and analyzing the ways in which desire functions. My dissertation will be a transatlantic study of desire and will further the ideas that I’ve been so passionate about since that seminar on Romanticism in my senior year of college.

PS. In case you’re curious–I have read Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner and therefore feel okay about using parts of Hogg’s title.

Never Have I Ever Read

At the beginning of summer, my husband, our two basset hounds, the cat and I moved into a little white rental house with a backyard. And once we had unpacked all our books, installed a makeshift closet in the back room (in the whole house, we have one tiny little 2×3 feet closet in the bedroom), and felt sufficiently settled to have company, we threw a housewarming party.

Naturally, ninety-percent of our guests were English grad students, and, as we were sitting around the fire-pit in our new backyard, someone suggested we play a literary version of the party classic “Never Have I Ever.” In the original game, the players take turns admitting to something they have never done (never have I ever been skiing–a sad truth!), and each person who has done the event loses a point until only one person is left with points, or something of the sort. In our version, we shamefully admitted works we had never read, and the other players were to put down a finger of the full ten with which they started. Of course, we awarded a slight handicap of negative five points to the only three non-bookish types (my husband the mathematician, a former history major, and a physicist) to make the game somewhat fair.

We were never quite clear on the goal of the game, since in our circle there seemed more pride in “losing” the game than surviving to the end with fingers still raised. In fact, one of our friends “lost” twice by the time we called the game. And we were all envious. But we went round and round, enjoying ourselves immensely.

“Never have I ever read Moby Dick.”

“Never have I ever read Huck Finn.”

“Never have I ever read Beloved.”

I have been studying for comprehensive exams for the past five months, and while I have read a significant number of the works on my lists in past graduate seminars, I feel like the whole process is a long game of “Never have I ever read…”

At the University of Kansas, where I am in my third year of doctoral studies, you compose three lists with your committee–two of which are time period lists (your area and an adjacent time period) and the third is a list of your own choosing (often an author, literary theory, a genre, etc). As a Romanticist with a fairly extensive background in Victorianism, I have chosen my period lists to form the full nineteenth century in British literature, and my final list is geared toward the Leigh Hunt Circle as I prepare for a dissertation focusing on Keats, the Cockney School, and how this context shaped his conception of “work.”

After reading criticism and biographies for the last two months as I try to whittle away at the dissertation list, I have switched to fiction for a much needed breather. I find it heartening to zip through a couple of novels in a week, when I have been slogging through nonfiction for what seems like a lifetime (and I will say I have read several “lifetimes” in that list, and highest praise must go to Nicholas Roe’s 2012 Keats biography. I have added it to the ever-growing list of books I wish I had written). In anticipation of the Halloween season, I scheduled myself several gothic novels in a row. And last week, I read Wuthering Heights for the first time.

Perhaps I just permanently altered your opinion of my clout as a nineteenth-century scholar. Well, so be it. I certainly admit the sad fact with a touch of shame. But now I have checked it off my list of never-have-I-ever-reads, and I have moved on to the next novel that somehow fell through the gaps in my long tenure as a literature student.

I feel this game “Never Have I Ever Read” haunts literature scholars. It certainly helps us flesh out syllabi–how else will we force ourselves to finally pick up Dombey and Son if we do not assign our students (and ourselves!) to read it?–and the game even fuels our research, it seems.

Three weeks ago, I had the pleasure of traveling to Portland and presenting on a Romanticism panel at the Rocky Mountain MLA. This conference has become a tradition for a couple colleagues and me, who would likely never travel and present together otherwise since our areas are so diverse. I presented on the connection between architectural structures and female bodies in Keats’s romances. I looked at the way in which the lived experience of female bodies, specifically in rape narratives, becomes abstracted into a symbol (the first step of which is the equation of the female body to the house or palace that protects her–i.e. Madeline is endangered because her house is penetrated in “The Eve of St. Agnes”). This cultural phenomenon is allegorical in so far as the female body comes to represent social bodies (structures) in various forms through literature and even political propaganda. The specific and material become crystallized into a generic trope that can be circulated, translated, and exchanged, depending upon the terms of its use, its ability to anger, inspire, manipulate.

In the Q&A portion of the panel, another presenter asked if I had read Cymbeline. I shook my head and shyly admitted I had not. Despite taking two courses in Shakespeare and Renaissance drama, never had I ever read, seen, or even heard a plot summary of the play. Nor is the classic John Middleton Murry volume Keats and Shakespeare listed among my secondary texts for comprehensive exams.

Nevertheless, I did my research that evening in my hotel room, and discovered much speculation on the play’s influence in Keats’s portrayal of Madeline’s boudoir. Indeed, Charles Cowden Clarke wrote, “I saw [Keats’s] eyes fill with tears, and his voice faltered,” as the poet read aloud from the play in summer 1816 (qtd. on page 56 of Walter Jackson Bate’s biography of Keats). In addition to speculation on the scenery, importantly, Imogen has been reading the story of Tereus and Philomela before falling asleep. According to Greek mythology, Tereus rapes Philomela and cuts out her tongue so that she cannot report the assault. Jove later transforms Philomela into a nightingale, and her song becomes an echo of sexual violence throughout literature, including T.S. Eliot’s “The Fire Sermon” in The Wasteland (a piece I have read many times since first crossing it off my never-have-I-ever list in high school).

Scholars speculate on what the literary greats have read (or not read) as an everyday practice. My fellow-scholar who asked if I had read Cymbeline was presenting truly stellar archival research that sought to uncover whether Keats had read various seventeenth-century ballads on nightingales. She lamented that we do not know to what volumes he had access while staying with Benjamin Bailey at Oxford in the summer of 1817. And as she had not yet read Roe’s recent Keats biography, she did not know the conflict between Bailey and Keats’s London friends, and why Charles Brown and other early biographers would not have contacted him to inquire about Keats’s reading that summer. Even in their lifetimes, Keats and Leigh Hunt gained the label “Cockney” as a class slur partially due to the fact that they never had ever read mythology in the original Greek, and instead got their knowledge of the classics through translations.

Next up on my reading schedule is Northanger Abbey, and I will be reading it for the first time. This will be my last novel for a while, and, as I want to preserve my reputation with you at least beyond my first blog post, I will not admit the Romantic poetry I will be reading next week–for the first time.