I recently started a series of prints that began in a flurry of ideas: the wonder of looking close, peeling back the layers, and the intensity of microscopic viewing.

I am trying to dig deeper, revisiting the circular plate and looking at a rich history of images that are inspired by the sphere. Continue reading “Research Turns Into Artmaking”

The Body on Display: A Day at the NYAM Medical History Festival

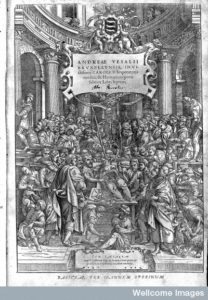

Late eighteenth century physicians (for the most part) increasingly  embraced the wisdom of learning anatomy directly from a dissected corpse. Feeling the textures and depths of the body’s interior and seeing it all firsthand became an invaluable tool for beginning physicians. However, this method of teaching ultimately relied on the advancements in medical thought demonstrated in the sixteenth century by one man: Andreas Vesalius. The brief version of his contribution to this field is that he turned a system in which the physician dictated dissection from a space removed from the actual body, and a surgeon performed what he was told on the body. Physicians, in this system, rarely encountered the actual interior of the body. Vesalius changed all that. Not only did he dissect his own corpses, but, by doing so, he corrected many of the errors in previous anatomical texts based on an assumed closeness between human and animal anatomies. His most famous work is the beautiful, fully illustrated De Humani Corporis Fabrica (often referred to as just the Fabrica). You probably recognize the frontispiece pictured here. Continue reading “The Body on Display: A Day at the NYAM Medical History Festival”

embraced the wisdom of learning anatomy directly from a dissected corpse. Feeling the textures and depths of the body’s interior and seeing it all firsthand became an invaluable tool for beginning physicians. However, this method of teaching ultimately relied on the advancements in medical thought demonstrated in the sixteenth century by one man: Andreas Vesalius. The brief version of his contribution to this field is that he turned a system in which the physician dictated dissection from a space removed from the actual body, and a surgeon performed what he was told on the body. Physicians, in this system, rarely encountered the actual interior of the body. Vesalius changed all that. Not only did he dissect his own corpses, but, by doing so, he corrected many of the errors in previous anatomical texts based on an assumed closeness between human and animal anatomies. His most famous work is the beautiful, fully illustrated De Humani Corporis Fabrica (often referred to as just the Fabrica). You probably recognize the frontispiece pictured here. Continue reading “The Body on Display: A Day at the NYAM Medical History Festival”

Misunderstanding Music Theory

By Andrew Welch

I’ve a problem I suspect is endemic to academia: the hopeless, near-pathological attraction to disciplines, fields, discourses, and texts I can’t understand, and likely never will. Is there a name for this malady? The worst part is that once a once-opaque knowledge begins to make sense, it loses its mystique. Perhaps this condition would be more tolerable if it didn’t so closely resemble the delusion of chivalric romance—or, for that matter, the troubled frisson of orientalism. I know that I know an understanding is just a calcified and stable misunderstanding. Whatever I think I know, I don’t. And any knowing is always dissolvable and resolvable. But once knowledge starts to feel understood—however poorly—something changes. It no longer exists out there, as something mysterious and opaque: it’s now in here, joined to my conceptual armature. Once appropriated, a concept becomes part of the machinery of appropriation. Continue reading “Misunderstanding Music Theory”

Peripatetic Scholarship, or, the Romance of Ideas

I’m reading from a used copy of Wordsworth’s Complete Poetical Works; there’s no date in the front matter other than a note giving the textual provenance as an earlier edition from 1857, but the pages are densely-columned and Biblically thin, and an inscription reads “To Rose with love. 1909.” The thing is hard to read and unwieldy, and I realize that I tend to forget that during the vast majority of Wordsworth’s reception history, readers didn’t pick up Broadview Press’s Lyrical Ballads, complete with both 1798 and 1800 editions, prefaces, notes, contemporary reviews, and scholarly appendices. Systematicity may seem like a professional mandate, but it’s also a luxury of modern scholarship. Continue reading “Peripatetic Scholarship, or, the Romance of Ideas”

A Romanticist as Curator

Introduction: I spent the better part of this summer—and the final months of my time as graduate curatorial fellow at the Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art—conceiving, planning, and executing my first art exhibition, Ecological Looking: Sustainability & the End(s) of the Earth. In this post, to open my blogging for the 2014-15 academic year, I detail how in curating the show I sought to mobilize the skills and expertise with which I’ve been endowed as a romanticist, generally, and aspiring William Blake studies scholar, more specifically. In doing so, I hope less to merely chronicle my own experience than to open up other possibilities of engagement for graduate students training in the field. I mean this especially with an eye toward curatorial work, an aspect of the academic and museum profession I believe a number of graduate students in the caucus might have a great deal to contribute (and which, of course, the NGSC alumnus Kirstyn Leuner already has). Continue reading “A Romanticist as Curator”

Why Franklin's Ship Matters to Romanticists

I was excited to learn, earlier today, that a Canadian marine expedition has located one of Sir John Franklin’s ships on the Arctic seabed, after a 160-year search for material evidence of the ill-fated Victorian voyage to find, chart, and claim the Northwest Passage. One archaeologist, William Battersby, has described the recent find as “the biggest archaeological discovery the world has seen since the opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb almost 100 years ago.” The ship, now resting on the sea floor, seems to have been preserved in fairly good condition, and the searchers hope to find artifacts from the voyage — perhaps even photographs — on board.

Archival Research: The Poetic Personalities Of Keats And His Circle

Hello and happy summer! Since I last blogged, I passed my Ph.D. comprehensive exams and spent two weeks in England. I presented at the Keats and his Circle conference along with my fellow blogger, Arden Hegele, and of course the conference was everything a Keatsian (or Romanticist) could wish it to be. Our weekend at Wentworth Place came complete with three days of really smart and innovative Keats studies, phenomenal featured lectures, and a “Keats walk” through Hampstead. But what I will talk about today is what I learned in the week after the conference. Continue reading “Archival Research: The Poetic Personalities Of Keats And His Circle”

Graphs in Romanticism Research

We are all aware of the hand-wringing that accompanies humanities scholarship in the early 21st century. Soon enough there will be another article announcing the death or worthlessness of the humanities degree. Subsequently there will be a rebuttal which points out how crucial the humanities are. And the cycle will continue. I am not trying to disparage that particular discussion, but I want to point it out as a symptom of the larger problem of how the humanities interface with the public. According to the public, there does not seem to be anything concrete that the humanities produce; of course that is not true, but it is hard to overcome that perception. One of the ways of overcoming that perception might be to offer alternative perspectives on our data. To that end, I want to further consider the graph, as a way of helping further humanities research. I will say that the goal here is to continue the discussion about whether or not the graph as a research tool can be useful for Romanticism; I am not sure the graph will be useful, but to understand the advantages and pitfalls of a new methodology we will need to have the discussion first.

One last item, before we go too much further: I would be remiss not to note Graphs, Maps, and Trees: Abstract Models for Literary History by Franco Morretti. That book and its various responses really started this particular conversation. I hope to focus the conversation on particular tool though, which is the Google Ngram Viewer. As you all are aware, the Ngram Viewer uses Optical Character Recognition (OCR) to search through Google’s database of digitized books. The Ngram Viewer is not perfect, to say the least. For example, it frequently confused the long ‘s’ as an ‘f’ up until recently. That being said, the Ngram Viewer does have some powerful tools available, not only allowing you to search for various words, but also parts of speech, most popular following words, and so on.

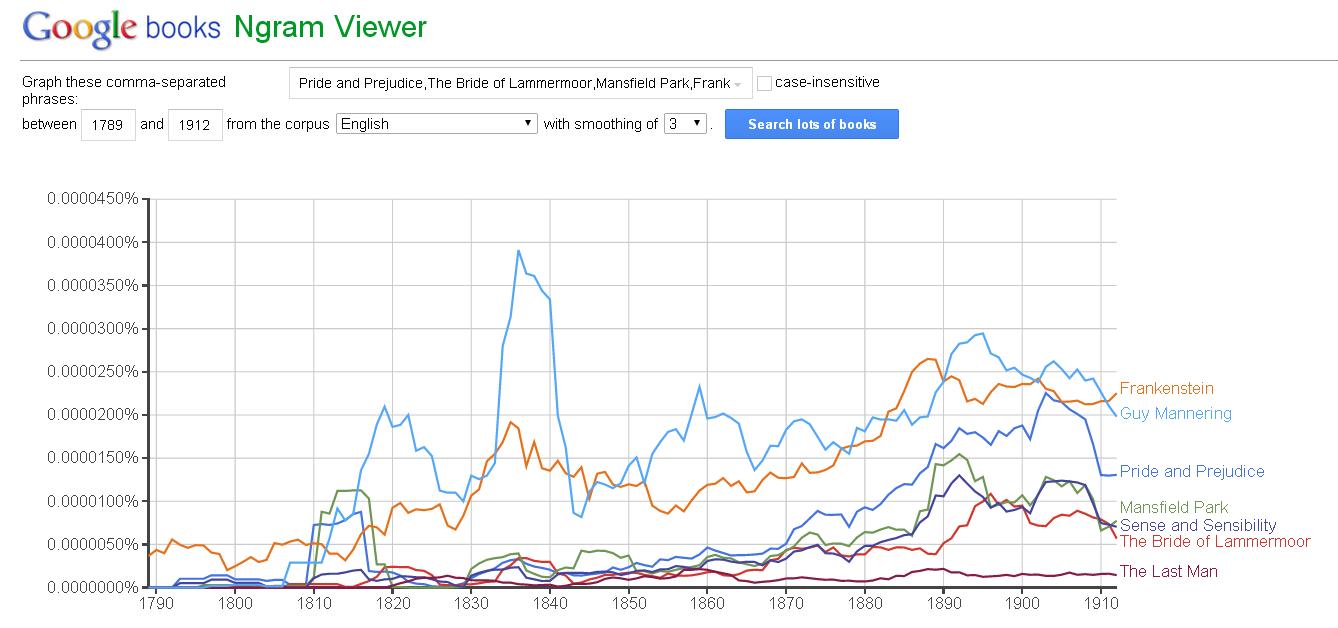

Here is a graph that charts the ‘Big Six’ from 1789 until 1912:

If you would like to see the original graph it his here: Blake,Wordsworth,Coleridge,Byron,Shelley,Keats Original. Among other items, this graph can tell us a few items: That Blake started off as the most popular, but that Lord Byron was the most popular of all of the six throughout the long nineteenth century, although there were a few moments where Shelley, Wordsworth, and even Coleridge over took him. And that Keats … was not quite as popular.

If you would like to see the original graph it his here: Blake,Wordsworth,Coleridge,Byron,Shelley,Keats Original. Among other items, this graph can tell us a few items: That Blake started off as the most popular, but that Lord Byron was the most popular of all of the six throughout the long nineteenth century, although there were a few moments where Shelley, Wordsworth, and even Coleridge over took him. And that Keats … was not quite as popular.

Or, at least it would be nice if the graph told us that. Due to the way that the OCR works, though, any mention of the words are gathered. So that a search for ‘Shelley’ will collect not only Percy, but also Mary, and their children, and extended family, or just anyone else named Shelley. Names that are a bit more unique, like Wordsworth and Byron, probably are closer to representing the writers I was looking for. But those searches will still gather information from other Lord Byrons and other Wordsworths, like Dorothy. For the purpose of searching for proper-nouns, the more unique the better. For example, here is a graph of more unique book titles:

The original graph is here: Pride and Prejudice,The Bride of Lammermoor,Mansfield Park,Frankenstein,Sense and Sensibility,The Last Man,Guy Mannering Graph. This data is a bit more valuable, because the likelihood of someone writing ‘Frankenstein’ or the words ‘Pride and Prejudice’ together, to refer to something else than the books is smaller (although not impossible). Noticeably, Sir Walter Scott’s novel is quite popular, although so too is Shelley’s. And, admittedly, if I extended the graph into the 20th century, Jane Austen’s novels would be more prominent.

The Ngram Viewer can also do a wildcard search, which I did with the word ‘French’ below:

Again, here is the original: French * Graph. At least for the time limit, the most frequent word to follow the word ‘French’ is ‘and’. That result is not particularly surprising, though, as and is a fairly common word. What did surprise me was that between 1812 and 1818 ‘army’ followed ‘French’ more frequently than ‘and’. Of course, Napoleon was attempting to conquer the rest of Europe during that phase of time (minus Elba). But I think that the concern or interest in the French army was so great that it surpassed an everyday usage is interesting. If someone were writing how, in a particular text, one can see the anxiety over the French army, this graph might help them reinforce their point.

I would also like to point out the “Search in Google Books” section. If you were to click on any of those date ranges, Google would take you to the books where it found the word in question. Also, that search section can show what kind of results the search is generating, whether Blake refers to William, or other Blakes.

Although this is a brief meditation, I think that there are a few items that I would like focus on. First off, I think it it plain that these graphs are no substitute for the closer readings that people in the humanities often perform. And there are problems with the graphs, they cast a net that is a bit too wide. There is though a few interesting advantages, like these graphs can help show very large historical shifts. The viewer can also help with a very formalist study, because of its ability to parse words (which I did not touch on here). But for the moment, I think that the very broad perspective of the Ngram Viewer might be useful to humanities research, in that it would help us illuminate historical trends just a little bit better. Graphs, and the Ngram Viewer tool, are certainly not perfect nor can they replace our normal methodologies, but they do have some potential for humanities research.

-Kent Linthicum

NGSC E-Roundtable: "Three Ways of Looking at Romantic Anatomy"

Introduction

Emily, Laura, and Arden are three graduate students who share interests in Romantic medical science and anatomy. We illustrate our contrasting methods in responding to this article (“Corpses and Copyrights”), which discusses the history of dissection in England through pictures of a medical textbook, William Cowper’s Myotomia reformata, or A New Administration of the Muscles (London, 1724) and legal issues with respect to both bodies and texts as shared properties. The article celebrates the connections between literary and medical fields through its focus on Laurence Sterne’s body-snatched corpse, and the rediscovery of his anatomized skull in the 1960s. In this collaborative post, we each respond to the question: how can our distinctive approach cast new light on such a text? Within the specific field of dissection, we focus on different approaches and questions with respect to the imaginative work of illustration and fiction to depict the body, the power of the body (and its parts) as an object and artifact, and the gendered nature of dissection and the spectacle it created.

Laura Kremmel is a PhD candidate at Lehigh University, specializing in Gothic literature, particularly in the Romantic period, but with teaching interests across all manifestations of the Gothic. Her dissertation considers Gothic literature in the context of medical theory and the Gothic’s imaginative ability to experiment with the limits of those theories and offer literary alternatives. She has also published on zombies and is currently developing an online class on ghosts and technology.

Emily Zarka is a PhD student in Romanticism at Arizona State University focusing on gender and sexuality studies and representations of the undead in the period. She is interested in tracing the literary history of horror monsters from the modern period, and exploring the different ways in which men and women write about and reflect on the undead. Emily has given public talks on why zombies matter, and has an upcoming publication exploring the undead in Wordsworth, Coleridge and Dacre.

Arden Hegele is a PhD candidate at Columbia University, with a dissertation focusing on Romantic medicine and literary method. Her most recent work explores Wordsworth and Keats’s hermeneutic engagement with post-Revolutionary techniques of human dissection, and she will soon be teaching a self-designed course about Frankenstein.

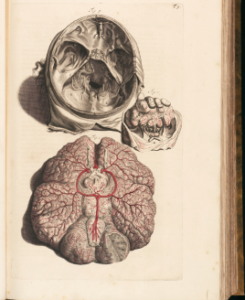

Laura

I love the ideas brought up in this article that conflate the actual bodies on the dissection table and the bodies depicted in the illustrations, and I’m most interested in the aspects of this comparison that get left out in able to make that conflation possible. What immediately strikes me about medical images of the eighteenth century is the sterility of the body and the cleanliness of it, which would not be an accurate depiction of the body on the dissection table: we’re missing all the fluids and the deformity of decay that would have made the body an object of repulsion and abjection. These “ugly” aspects worried Dr. Robert Knox (of Burke and Hare fame), who was disgusted by the interior of the body and thought that seeing it would actually ruin an artist’s sense of beauty (Helen MacDonald writes about this in her book, Human Remains (2006)). In his Great Artists and Great Anatomists (1825), Knox pleads with the artist to always draw a dead arm next to a living arm in order to preserve a division between the dead body as an object of disgust and the beauty of the living. Earlier, in the introduction to his Atlas of Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus,” William Hunter explains that there are two ways to illustrate the cadaver: to draw it exactly as it is shown, thus accurately reproducing one single body, OR to draw it taking into consideration all of the other bodies you have seen, thus producing an informed idealization of the body. Hunter himself claims that he much prefers this second, more imaginative method of depicting anatomy.

Thus, the illustrations take on the ability to fictionalize the body to some extent, prioritizing a style that would serve a pedagogical purpose, if not a realist one. It emphasizes the act of seeing the body, but only seeing the right kind of body. The same is true for preparations made of the body, and John Hunter is famous for making thousands of these: isolated and “prepared” parts of the bodies that would become preserved for the purpose of teaching anatomy (and, indeed, to carry on the idea of the body as property and commodity, unique preparations and parts of the body were a common gift to and from physicians). This is also the way in which fiction plays with ideas of the body, uninhibited by the limits of current medical knowledge. Physicians understood the essential role of the dissected body for understanding anatomy, but physiognomy remained somewhat in the shadows: without opening a living body, it was difficult to grasp how it worked. Thus, they were frustrated by exactly the distinction to which Knox refers. The Gothic is particularly interested in the interior of the body–a large part of which produces fear and shock–and it has an ability to stretch the limits of the body, both living and dead, in ways medicine could not. Writers like Matthew Lewis took the opposite approach to most medical illustrations, embracing the abject body and all its dripping, oozing effects, exploring new ways for the body to function in the process, expanding ideas of vitalism, circulation, and digestion.

Many writers of the Gothic were physicians themselves or close to medical thought, such as Mary Shelley and Lord Byron (close to John Polidori), and dramatist Joanna Baillie (niece of John and William Hunter and brother of Matthew Baillie, who spearheaded an interested in autopsy). The underlying principles of dissection are inherent in many of these works, especially the emphasis on empirical observation of the body in order to understand it. Much critical work has been written about Baillie’s play De Monfort (1798), which ends by displaying two bodies side-by-side (a murderer and his victim) in a type of moral autopsy. The murderer, De Monfort, had been so affected by seeing the corpse of the man he killed that it drove him mad and caused his death. In cases like this, the emphasis on seeing the body, whether on the dissection table, the illustration, or the stage, enters into other areas, such as commercial gain (as the article explains), as well as justice.

Arden

What I find compelling in this article is the emphasis on body-snatching as a way of experiencing a privileged intimacy with a literary legend: here, the act of dissection becomes a physical method for the exegesis of both a literary body and a body of work. As “Corpses and Copyrights” describes, Sterne’s body was taken from his grave and recognized as being the author’s by students in the autopsy theatre. This particular grave-robbery of a literary lion was, apparently, a chance one, prompted by the medical school’s need for demonstrational corpses. As Keats’s hospital training confirms, most corpses for autopsy in the Romantic period were indeed procured by body-snatchers, who were paid off by Sir Astley Cooper and other major surgical instructors. And, since some European medical schools guaranteed their students 500 bodies annually, odds were good that students would eventually identify their “Man in the Pan.”

But, with the disinterred shade of Shakespeare’s Yorick hanging over Sterne’s corpus (“Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him well, Horatio”), we do have to wonder about Sterne’s actual disinterment as serving a more deliberate purpose. As Colin Dickey’s book Cranioklepty (2010) discusses, the purposeful body-snatching of artists was surprisingly prevalent during the Romantic Century. Other artists suffered similar fates to Sterne’s: Haydn, Beethoven, and Mozart’s skulls were reportedly stolen from their graves by admirers (in Mozart’s case, since he was buried in a pauper’s grave, the future thief placed a wire around his neck before burial to help identify him later); in 1817, a malformed skull reported to be Swedenborg’s was offered up for sale in England; Schiller’s skull was mounted by a noble friend in a glass case in a library in 1826; and Sir Thomas Browne’s skull entered the Norwich and Norfolk Hospital Museum in 1848. More familiarly, the physical tokens of the Romantic poets continued to circulate after their deaths: Shelley’s heart was snatched from the funeral pyre and preserved in wine, while (in spite of his request to “let not my body be hacked”), Byron’s autopsy was published, his internal organs were scattered throughout Europe, and his corpse was disinterred in 1938 and lewdly examined in the family crypt. Even now, the Keats-Shelley house at Rome boasts various physical relics of the poets, including locks of their hair.

Why were (and are) Romantic artists’ dissected bodies so fascinating? For me, the anatomizing of Sterne’s skull, which bears marks of abrasions from medical implements, reflects on an important moment in the advances of surgical dissection and autopsy at the end of the eighteenth century, as the parts of the dissected literary body became relics for reanimative reading. Though Sterne’s dissection might be coming out of the anatomy in a satirical tradition (like Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy [1621]), as Helen Deutsch describes in Loving Dr Johnson (2005), at the end of the eighteenth century, the autopsy of a literary giant could bring the reader into an intimate encounter with the truths of his or her body, and even offer a kind of memorializing reanimation. In the case of Johnson, the Preface to the 1784 published account of his postmortem (“Dr Johnson in the Flesh”) described the corpse as “a work of art” that was still “of importance to his friends and acquaintances,” and the postmortem text is positioned as a way for the bereaved Johnsonian to reanimate the body through a deep encounter with its fragmented parts. Boswell’s Life of Johnson (1791) picks up the same language of reanimation through dissection: the directly reported records of Johnson’s speech allow the reader to “see him live,” in contrast to other biographies “in which there is literally no Life.” For Deutsch, this is part of a broader eighteenth-century trend of sentimental dissection: the body of the eponymous heroine in Clarissa (1748), for instance, is “opened and embalmed,” and Lovelace promises to keep her heart, which is stored in spirits, “never out of my sight.” (The real-life corollary of this is perhaps the circuitous journey of Percy Shelley’s heart, the “Cor Cordium” acting as postmortem metonym for the poet’s self). For the Romantics, insight into a fragmented body part seems to have had a reanimating quality for the whole body, and, as I think about it in my dissertation, I find links between medical dissection of human bodies, and practices of excisional close reading of organic literary forms, during the Romantic period.

Emily

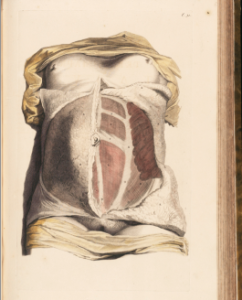

Upon examining these illustrations and the accompanying article, I was immediately struck by the gendered implications, namely the differences between male and female dissection and how those acts were illustrated. The article claims that “Usually, the bodies used were those of criminals or heretics – predominantly males in other words. The occasional dissection of a woman, it being a public event, attracted large numbers of spectators by the prospect of the exposure of female organ.” Given the ideas of the time that the female body was somehow more sacred or special because of the presumed virtue of the female sex, it does not seem unsurprising that the male body would be more readily violated after death in such a way. However, the connotations of penetration from the scalpels, forceps, and other tools of dissection seem relevant here especially because they all were wielded by a masculine hand. These sharp blades and other disruptive instruments separated, cut and otherwise maimed flesh in an extremely intimate way. When this was occurring with male corpses, there are of course homoerotic undertones, but what really seems relevant is how this violation of phallic metallic apparatuses was deemed taboo except in rare cases. This might in part explain the public audience that attended female dissections as suggested above. Not only was flesh usually hidden promised to be revealed, but the feminine body was in death capable of being poked and prodded in ways living human males could only dream of. The intimacy of such an act becomes fetish as the public gathers to watch the male scientist push the scalpel further and further into the most intimate areas of a woman’s body.

The framing images displayed in “Corpses and Copyrights” appear to validate the theory that even dead bodies were gendered and sexualized in traditional ways. The first image of the series is the front view of a beautiful, naked woman accompanied by props and scenery reminiscent of Neoclassical art and the Grecian and Roman sources that movement drew its inspiration from (see the Roman copy of Praxiteles’ Venus). The only two places marked on this woman’s body are the breasts (A) and vagina (B), highlighting the parts of her body directly associated with sex and reproduction. We can assume that those areas were meant to be detailed one another page in their segmented, dissected form; when the sex separates from the body and becomes an object of its own. Detaching the female form from the person it belongs to would hardly be considered shocking given the culture of the time. The final image in the illustrative series is another woman (possibly the same one, but with a different artistic arrangement), only this time is is her backside that is drawn and marked. Here the letters adorning her body are more numerous, with areas such as the spine, calves and shoulders given special attention in addition to her bottom. I am fascinated by the artists decision to show only a complete female form, although I am not surprised. To me it suggests not only that the female body, at least in its intact form, is considered more beautiful, but that again the connections between sex and death dominate.

Additionally, the “corpse as commodity” idea challenges the idea of death as escape for men and women alike. For in a culture where women were considered property of men both theoretically and legally, death might be a release from such patriarchal control, albeit in an extremely morbid way. As “Corpses and Copyrights” asserts, “the body was not regarded as property” once dead, and therefore the female could finally be free from her masters, at least in theory. The value given to corpses and prevalence of grave robbing for medical and scientific purposes perverts this supposed freedom by once again giving monetary value to the body, and as the popularity of public female dissections suggests, yet again makes the female form a more rare and valuable object to possess. All of which proves that during the period, nothing could be separated from the politics of patriarchy and gender.

(All images in this post are from Cowper’s Myotomia reformata, and first appeared in “Corpses and Copyrights.”)

Interview: Dr. James McKusick

One of Romanticism’s favorite ecocritics, Dr. James McKusick, explains how getting lost in the woods at the age of five helped inspire his brilliant book, Green Writing: Romanticism and Ecology. He shares, “I was playing with some friends and they went home. I went the other way and I was lost on my own for a couple hours. I finally found my way to a house in the woods, where there was this little, old lady, who decided not to make me into soup. She actually called up my friends’ parents, who rescued me. It’s one of those formative childhood memories. The takeaway is that I’ve always wanted to wander in wild places. It’s part of my makeup.”

Scholars of Romanticism should be thankful for a couple of things: first, that the old woman in the woods did not make McKusick into soup and, second, that the curiosity and bravery that five-year-old McKusick demonstrated in his exploration of the woods has grown and can be seen within his scholarly work in our field.

INTERVIEWER

How did you become interested in ecological approaches to Romanticism?

MCKUSICK

I’ve probably spent five years of my life out under the open sky. However, it never occurred to me that I could translate any of this into the practice of literary study or literary criticism until long after I was out of graduate school. My dissertation had nothing to do with wilderness—it had to do with the philosophy of language. It was only after I got tenure, on the basis of that work, that I put my head up and I said, “What do I want to study next?”

At that time, there was no such thing as ecocriticism. This was the late 80s, early 90s, and Jonathan Bate had just published his first book on Wordsworth and green Romanticism, but with that exception, there wasn’t that much out there in specifically the field of British Romantic or Transatlantic ecocriticism. Obviously, there’s a long and distinguished history of people who study environmental writing, especially in the American context. That’s really, I think, the center of gravity for the field of environmental writing. If you look at most anthologies of nature writing, they have to deal with mostly 19th-century essay writers, Thoreau, Emerson, and that whole tradition down to Rachel Carson and modern times. But what’s missing in that tradition is the deeper history that goes back to at least the Middle Ages, perhaps the Classical period. The deeper intellectual and spiritual history of nature writing is what I’m after.

There was just a morning when I woke up, and I had this Gestalt experience, where I said, “You know, I love wild, natural, places, I love literature, I want to bring those things together.” It made sense in terms of my own life journey, but it was also an edgier, more dangerous field to go into because there wasn’t such a field yet. I got to be in there at the creation, so to speak. Organizations such as ASLE were just starting to be formed […] There was an aha! moment as well, where I found the poetry of John Clare, a lesser studied British Romantic poet, who, especially at that time in the 80s and 90s, was virtually unknown to Americans. British scholars have always known about Clare, but they, perhaps, have not taken him as seriously as he should have been taken. They used to speak of poor Clare, the poor mad poet. They knew a few of his poems that he wrote in the madhouse, but they didn’t know the reams and reams of wonderful poetry that he wrote during the primary phase of his poetic career, when he was not in the madhouse, when he was just a peasant farmer living his life out under the open sky.

John Clare was an amazing discovery for me. I became well acquainted with the world’s leading scholar of Clare studies, Eric Robinson, who is also the main editor of Clare’s work. Eric became one of my great mentors […] Through the study of John Clare, I’ve come to a more comprehensive understanding of what environmental writing is or can be. What I love about John Clare is simply his authentic connection, his groundedness in a particular wild place. John Clare was there at a transitional moment in the history of British agriculture, when they were moving from the ancient common field system to the enclosed or private field system. He deeply mourned that transformation of the landscape. The enclosed fields were being intensively cultivated. It was kind of a green revolution in agriculture, which made the lands more productive, and, in a sense, industrialized the land. It also destroyed many of the wild creatures that lived there, their nesting places, their habitat. Clare was really the only person who seemed to care. It was a tragedy that affected the landscape, and this is all captured beautifully through Clare’s poetry, through the poetics of nostalgia. He writes about land the way it was, but he also uses the poetics of advocacy. He advocates for preserving the landscape and for the rights of the creatures that inhabit there. Clare’s poetry is either naïve or deeply, mystically, connected with the landscape. I prefer the second idea.

Discovering Clare was a huge milestone. My first article in ecocriticism was my article on John Clare and I had a terrible trouble finding anyone who would publish it because it was perhaps ahead of its time. There was something about it that didn’t sit well with the literary establishment. I finally published it with a literary journal out of Toronto […] That turned into a chapter in my Green Writing book, which probably took me ten years to write. I took my time with that book because I was discovering my methodology as I went along. There was no one I could sit at the feet of and learn how to do ecocriticism.

INTERVIEWER

What does an ecological reading open up about texts that other readings do not?

MCKUSICK

One of the real landmark pieces of work in ecological criticism has been done by Lawrence Buell. He addresses the question, “What is an environmental text?” The answer to that question is all texts, because every text has an environmental context. That environmental situation can be overtly expressed in the text or not […] If you just think of ecological criticism as “the study of nature writing,” it tends to marginalize it before you even get out of the starting gate. You’re only going to look at texts that are often in a fairly boring way describing “pretty things in the natural world.” There’s not really a lot to say about that, other than “how pretty!” That’s not what an ecological reading is or should be. What Buell teaches us is that every text has an environmental dimension. If it’s by a sophisticated writer, this dimension will be overtly manifested in the text in some respect.

We also need a broader understanding of ecology to realize that it is the study of everything that happens in the world. It isn’t just simply the study of wilderness, which is the other category mistake that people make in looking at ecological writing, the study of wilderness theory or wilderness areas. That’s a big piece of ecological criticism, but it is not the only piece. To be a good ecological critic, you need to look at urban as well as rural landscapes, land as well as ocean, and the sky is important. There’s nothing that gets left out of an ecological reading of a text. An ecological reading of a text can also poke at what is not there, what is not manifested in the text, but should be, or is repressed […] One of the best things about ecological criticism, I think, is that it is linked to a larger environmental movement that is gaining more and more headway in our larger society as we speak. To me, it seems a lot more authentic for literary scholars to be engaged in the struggle to protect the environment than it does for us deeply bourgeois professors to be involved in something we call the class struggle and the liberation of the common man. Somehow, that doesn’t ring authentic.

The other beautiful thing about ecocriticism is that it’s a methodology that has legs and can travel into any literary course, no matter the period or the genre or the subject matter under consideration. It can be used as a skeleton key to open up texts and see dimensions that our students truly care about. Our students care about sustainability, they care about environmental preservation. So I try to embed ecocriticism into any course that I teach. It also allows an interdisciplinary conversation to take place. If you have students from the sciences, or engineering, or music and theater, they can call relate to this content in a way that makes literary studies more relevant to their own individual circumstances […] Certainly, ecocriticism is not intended to drive out every other method of literary analysis. It is meant to complement what we already have. It’s another set of tools to put in the toolbox.

INTERVIEWER

Your book engages the idea of the pastoral, citing the 18th-century context of the construction of “English gardens’ that imitated the idyllic disorder of natural landscapes, rather than formal geometric patterns” and, from my understanding, trace how “a true ecological writer must be ‘rooted’ in the landscape, instinctively attuned to the changes of the Earth and its inhabitants” (20, 24). I’m struck by several things here. If true ecological writers must be attuned to the landscape, might we view them as a collector? And, if we can view them as a collector, how might we negotiate issues of authenticity?

MCKUSICK

The idea of the pastoral, of course, goes back to the ancient times. The ancient Greek writers invented the concept of the pastoral landscape, and it’s very related to their form of agriculture, which was pastoral—in other words, they kept sheep, or goats, or cattle on the landscape. The pastoral ideal was invented by urban poets who were nostalgic for this older lifestyle that still existed in remote places. In historically recent times for these poets, this lifestyle had been replaced with more intensive forms of agriculture, the cultivation of crops. Urban life, of course, is not possible unless you’re cultivating a crop like wheat. The pastoral is always inherently nostalgic. It is always looking back to an earlier time where things were better and more peaceful.

Let’s bring it up to the 18th century. William Gilpin invented the concept of the picturesque. He was also a landscape designer, so he, along with a fellow called Capability Brown, invented the idea of the English garden. The English garden was an exercise in nostalgia. It captured a lost pre-history of wild landscape that the lands didn’t currently possess—in other words, all of English land has been cultivated since the Middle Ages, and the only wild lands that now exist are those that have been created by fencing. […] That’s where you get forests in English landscapes.

In the 18th century, the English garden is a reaction against French landscape. The garden at Versailles is a good example of a French landscape, which is geometric in pattern, and intentionally uses very artificial plantings to create a mosaic of color patterns. The English garden is a reaction to that—it uses simple and natural ingredients to fashion a pseudo wild landscape onto the pre-existing agricultural land. A feature you know from Jane Austen is the ha-ha, which is a sunken fence. The sunken fence is meant to be invisible from the perspective of the great house, so you look out upon an unbroken greensward. It prevents sheep from coming all the way up to the door of your house. It creates lawns. I blame the American lawn on the picturesque movement in British landscape architecture. People like William Gilpin and Capability Brown felt that instead of these patterned flower gardens, you should have greensward up to your very door. That, for some reason, has been the most enduring legacy of the picturesque movement in landscape. Even to this day, every American homeowner believes they should have a patch of greensward, even if they’re living in the Arizona desert. They have to have their green patch of grass next to their house, otherwise it’s not a proper home, and they need a white picket fence.

To come to this idea of collecting, collecting is at the very heart of the picturesque ideal. The central concept of picturesque landscape is that it resembles a painting, and it only resembles a painting at certain points of perspective. As you walk through a picturesque landscape, it is intentionally designed to give you prospects—specific places where you can gather a picturesque view. As you progress through the landscape, it’s designed so you go from one picture to the next. It’s like a slideshow. The very act of looking is an act of collecting. You’re creating a picturesque memory for yourself.

There’s a technology called the Claude glass. Claude is a French landscape painter who used a convex mirror to create an image of the landscape, which he would then either directly project upon a piece of paper and trace, almost like a camera obscura, creating a photographically “real” image of the landscape onto a piece of paper; I use the word “real” in quotation marks because it’s not inherently real, it’s just one form of perspective that has been naturalized to us Westerners. Since the Renaissance, we’ve used perspective drawing to create an image of the natural world, so when we do that photographically, it looks real and natural to us, but to folks from non-Western cultures, who don’t have a tradition of landscape painting, a photograph looks weird […] When Native Americans saw profile pictures for the first time, they didn’t accept them. They said, “That’s only half a man.” They only accepted full-face pictures […] The Claude glass was a technology imported from France and used by landscape designers to test the validity of a certain landscape solution. They would stand in front of the landscape, back to it, look at the Claude glass, and because it is a convex mirror, it also emphasizes foreground elements and minimizes background elements. It’s also a darkening mirror; it shades out certain things in the landscape. It is an intentionally intensifying artificial production of landscape, which can then be put on paper and be made into a painting. Even people who were not painters, people whom we would call tourists, would bring their Claude glasses into picturesque places in the late 18th, early 19th century and collect landscapes. They would literally stand with their back to the landscape, looking into their Claude glasses, and say, “Ah! That is picturesque.” In a way, the created landscape, in the mirror or on paper if they could sketch it, was even more real than the thing itself. It mattered more. That was the act of collecting a landscape. We do that today, only we do it with cameras.

INTERVIEWER

It’s like when people go to a concert and watch the entire performance through the screen of their iPhone as they try to record it.

MCKUSICK

Exactly. The whole phenomenon still exists today of snapping landscapes. Usually, there needs to be a figure in the landscape. Tourists are notorious for posing their wives in front of famous monuments and taking a picture. Somehow, that validates the experience. The act of collecting landscapes has certainly existed since the 18th century and already began to be parodied by the early 19th century. There was a whole wonderful set of satirical sketches, or cartoons really, of a character called Dr. Syntax, who would go out into the world and was a bumbling idiot, but still was attempting to collect picturesque landscapes.

The picturesque movement also had a very deep impact on the poetic tradition. There was a whole genre of 18th-century poems called prospect poems—a late example of that is “Tintern Abbey,” which is probably the single most famous prospect poem in literary history. Wordsworth is taking in a prospect a few miles up-river from Tintern Abbey and that’s what the poem is about. The prospect poem, then, lies at the heart of Lyrical Ballads, which is the book that kicked off Romantic poetry for England. The whole notion of the picturesque landscape and the prospect poem really inaugurates the Romantic movement, although the Romantics don’t simply take it over in a naïve way from the 18th century tradition. They sophisticate it, which is good. In its raw form, it’s pretty inauthentic. Wordsworth is already doing something very sophisticated in the prospect form, and Shelley will further internalize it. The “Ode to the West Wind” is a kind of prospect poem that, however, has become deeply psychological to the point where there’s hardly any landscape left to the poem; it’s all an internal landscape. “Mont Blanc” is another example of a prospect poem that presents an entirely internal landscape. Good for Shelley—he took something that was something inauthentic and boring and made it fascinating and complicated and inscrutable.

INTERVIEWER

So, an ecological writer is less authentic if they collect the land.

MCKUSICK

Yes. I think, still, there’s huge amounts of Romantic poetry that derive generically from the prospect poem, but the Romantics have taken that to much deeper psychological depths, demonstrating a much more sophisticated understanding of landscape. My favorite poet in this line is John Clare, who doesn’t do prospect poetry because it is also marked as a bourgeois writing form. John Clare is inhabiting landscapes, so his perspective is not that of a prospect poem, but it is experiential poetry of a dweller in the land. John Clare is a wonderful litmus test to put up against any other poet because John Clare is the most authentic poet in the whole British tradition.

A prospect poem is often stationary, where it goes in a series of slides, whereas in John Clare, it’s a dynamic landscape. You’re walking through it, you’re experiencing it, it’s washing over you, and its inhabitants are talking to you or you’re seeing it through their eyes. You can put a John Clare poem up against any other Romantic poem as a test of authenticity, and some will test out fine and some will not. I’m sorry to say another favorite poet of mine, William Wordsworth, often comes across as seeming inauthentic when you put him up against John Clare because he certainly does have a bourgeois point of view. It’s not that of a dweller, it’s that of a tourist, strolling through the landscape, pausing to take in a prospect, and having a deep mental reaction to that. Wordsworth is profound, but still perhaps less authentic in terms of his relationship to the land, than someone like Clare who was working with the land. […] Wordsworth was reading Gilpin, who writes about the English Lake District. There’s a very direct pipeline of ideas from the picturesque into the Lake District poets; Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Southey were direct inheritors of the picturesque ideal, but they do new things with it.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have any advice for graduate students in the field of Romanticism? What are some things that you wish you knew/were glad that you knew when you were in graduate school or approaching the job market?

MCKUSICK

I have tons of advice, but I want to address this, in part, from the view of ecological criticism. I guess my most fundamental advice to graduate students is to expose yourselves to all different types of literary criticism. No single method is correct or viable or valid on its own, and that certainly applies to ecological literary studies as well as any other “ism”. The last thing you want to do as a graduate student is to say, “Oh, I’m open to all ideas, and I have none of my own.” A grad student does need to stake out their turf and know what “ism” they’re going to be loyal to and really pursue that. But one still has to be capable of intellectual growth. The thing not to do is to be locked into a narrow or ideological reading of literature that blinds you to other dimensions of a text. Ideally, as a literary critic, we want to understand everything that’s there, including the things that are unspoken in a text. As one of my professors liked to put it, “the white space between stanzas are just as important as the stanzas themselves.” The subliminal thinking that is not overt still needs to be understood.

How do you become broadly learned? Hopefully, in a strong English department, there are going to be lots of ideological factions at work. Get to be friends with everyone and learn what everyone is up to and doing. Find which approach works best for you. Hitch your wagon to a star. No one really told me this when I was in grad school, but it really matters who your faculty mentors are because they’re networked into the profession. You want the most prestigious, the most connected, the most famous person, who is also going to be the most busy and the least likely to give you lots of personal time. Hopefully, you can find a golden mean of someone who is A. famous, but B. also a genuinely good person who will give you tons of time and attention and care and feeding and good criticism. It’s great to have arguments with your mentor! You’ll learn more by arguing with them than just agreeing with everything they say and saying, “Oh thank you, great famous professor.” Argue with them. Disagree with them. Test your mettle by going out on a limb and saying something a little dangerous or difficult. Graduate school is a wonderful time to try on new suits of clothes, especially as you’re doing your coursework or coming up toward a dissertation topic. Try to avoid something that is boring or conventional. Try something that is edgy, that puts you into terrain that you’ve never explored before. Often, through the beauty of interdisciplinary study, you can find terrain that no one has explored through that point of view before. Be a little offbeat. Be a little inventive. The world does not need another reading of “Tintern Abbey” or “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” The world needs to find texts that are less travelled by.

One thing that has changed in literary study in the last twenty years is the world has become flat. It used to be that only students at the most prestigious universities would have access to the best rare book libraries, the unpublished manuscripts. Now, everything is available through the wonders of Google Books or interlibrary loan. You can get virtually anything that has ever been published. Yes, you still need to go to rare book archives to get at the original, unpublished stuff, but you can do amazing things through the miracles of electronic publication and the whole field of Digital Humanities. Digital Humanities allow you to do all kinds of digital textual analysis and discover things that have never been seen before. I’ve done some of that work myself through things like corpus linguistics, where you can do statistical analyses of style. Things that were never possible have suddenly become achievable […] Don’t assume that your professors know these tools. Grad students might have an edge on the new technologies of textual analysis that are only possible through “big data” approaches such as corpus linguistics and stylometrics. The beauty of it is that you can predict things and find out that, yep, that’s real. It’s a brave new world out there, so make a daring prediction and go and do your textual analysis and find out if it’s true. No previous generation of grad students could do that, so you guys are going to own the world!