I know the beginning of the semester (or really any time during the semester) is not the best time for a book recommendation. But, I think you’ll forgive me because this is a fun one and packed with your favorite “literary characters.” Andrew McConnell Stott’s The Poet and the Vampyre was released late in 2014 and is a biographical amble through the events great and small surrounding the fateful weekend in Diodati that produced the monsters we have come to love. Yet, it also self-consciously dances around that stormy night—one that we can all agree fascinates scholars but has been written about to (un)death—in favor of an in-depth look at the relationships amongst these young poets and poetesses that brought them together and split them apart, primarily focused on Byron’s influence (and curse) upon his young doctor, John Polidori. For years, I have been an apologist for Polidori and his novella, The Vampyre, both of which often get shoved to the side for being important but not necessary or enjoyable. Here is finally an attempt to bring Polidori to life, not just as the spiteful tag-along of more successful poets but as the sympathetic victim of other people’s celebrity. Continue reading “The Poet and the Vampyre: Caught in the "Byron Vortex"”

The Year Without Summer; or, What Happened in 1816?

By Talia Vestri

With the rapid pace of today’s technologies, the news of any event happening anywhere in the world seems to travel at almost light speed to everywhere else. Whether through Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, or online journalism, the news of a missing jetliner in Southeast Asia or an earthquake in Japan can become common knowledge on the other side of the world almost instantaneously (unless, apparently, the event happens in Africa, but that’s an entirely different topic). Imagine, then, living in an era when the impact of a natural occurrence like a tsunami or hurricane would never be heard about for those who did not experience the phenomenon first hand—a time when news didn’t just travel more slowly, but sometimes didn’t travel at all. Continue reading “The Year Without Summer; or, What Happened in 1816?”

Objective Reading

Reading is not one thing but many. Most of all, reading is not passive. “In reality,” writes Michel de Certeau in the opening of The Practice of Everyday Life, “the activity of reading has on the contrary all the characteristics of a silent production.” But what are we producing? And what does the scholarly practice of reading do to this production?

As graduate students we often expect ourselves somehow to swallow texts whole—to get them. We try mightily to read texts simultaneously in terms of their own coherence, elisions, and indeterminacies as textual systems, of their unconscious procedural expression of determinant historical conditions of possibility, of their own stated and unstated relations to their intellectual precursors, and in the light of their reception by scholars or later links in the canonical chain; we strive to keep in mind texts’ political ramifications, how their formal-generic elements engage with other morphologically-related texts, and their relative sympathy or antipathy to various major philosophical concerns or strands of ideological critique; we read texts to find out whether we can instrumentalize our readings for the purposes of conference papers, dissertation chapters, or course syllabi—and maybe to determine whether we like them. More often than not, while reading I am also planning on passing along certain passages to colleagues or photocopying them for friends outside of the academy; wondering whether I could get a pirated PDF instead of waiting the several days for Interlibrary Loan or maybe shelling out the cash for a nice sixties paperback copy of my own, speculating about the biography of the author or the business-end realities of the academic press in question, and so on. Continue reading “Objective Reading”

Graphic Learning: Examples of Well-Researched Comics

It seems pointless to argue that graphic novels have an important place in literature at this point. Personally, I took two classes during my undergraduate career that incorporated such texts (including Satrapi’s Persepolis and Bechdel’s Fun Home), but more often than not this is a rare occurrence and something I did not encounter in my graduate coursework. Graphic novels often do not get the attention they deserve, in part because many deem them déclassé due to their graphic nature and/or subject material, but also because they are hard to teach. While graphic novels can be analyzed through literary theory (and should be), the format itself, and most notably, the visual element of such narratives, are in a scholarly discipline all their own. One cannot teach, or even fully enjoy a graphic novel, without at least a bare minimum knowledge of art theory and visual composition. (Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art and Critical Approaches to Comics: Theories and Methods are good places to start.) But then again, neither of these things occupies some alien universe detached from what we as literary scholars already tackle. Continue reading “Graphic Learning: Examples of Well-Researched Comics”

Guest Post: Another Kind of “Gentlemen’s Club”: A Brief Illustrated History of an Institution

By Katherine Magyarody

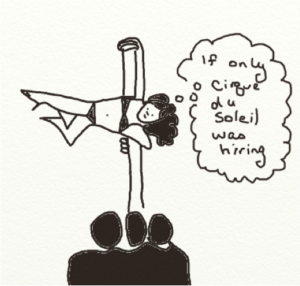

The contemporary gentlemen’s club may be encapsulated in the image of scantily clad women performing impressive acrobatic routines in front of a beery audience rather less capable of similar athleticism in a windowless building that clings to the seedier edges of town. It seems a fine irony that these strip joints, with their sticky, slick furniture, skewed sexual voyeurism and spilt beer take their moniker from establishments adjoining London’s centre of power, which excluded women, and had large windows from which the elite could watch the world outside without being seen.

The contemporary gentlemen’s club may be encapsulated in the image of scantily clad women performing impressive acrobatic routines in front of a beery audience rather less capable of similar athleticism in a windowless building that clings to the seedier edges of town. It seems a fine irony that these strip joints, with their sticky, slick furniture, skewed sexual voyeurism and spilt beer take their moniker from establishments adjoining London’s centre of power, which excluded women, and had large windows from which the elite could watch the world outside without being seen.

Our modern gentleman’s club’s idea of the gentleman is as flat as its beer and as restricted as a bouncer’s facial expressions. There is a much more interesting story to be told, one that tracks the evolution of masculinity and gentility throughout the nineteenth century while touching on wider patterns of socialization. Continue reading “Guest Post: Another Kind of “Gentlemen’s Club”: A Brief Illustrated History of an Institution”

The Joy of Colloquium: Recipes for Workshop Success

It’s that time of year when we come together with those close to us to celebrate, before the year ends, the things that really matter… like conference proposals (NASSR’s is due January 17th!), chapter drafts, readings from new books, and the other standard fare of the nineteenth-century working group. But concocting the perfect colloquium moves beyond a craft to become an art form, and it is the aim of this post to give you some pointers on preparing that rare colloquium that is truly — well done.

Continue reading “The Joy of Colloquium: Recipes for Workshop Success”

Dissertating with a Hammer: An Idiot’s Generalizations on Scholarship and Activism

I begin with two passages that will be the epigraphs to my dissertation:

Few critics, I suppose, no matter what their political disposition, have ever been wholly blind to James’s greatest gifts, or even to the grandiose moral intention of these gifts … but by liberal critics James is traditionally put the ultimate question: of what use, of what actual political use, are his gifts and their intention? Granted that James was devoted to an extraordinary moral perceptiveness, granted, too, that moral perceptiveness has something to do with politics and the social life; of what possible practical value in our world of impending disaster can James’s work be? And James’s style, his characters, his subjects, and even his own social origin and the manner of his personal life are adduced to show that his work cannot endure the question.

On First Looking into…Manfred

By Julia Malykh

The enchanting sensuality of Lord Byron’s closet drama Manfred (1816) lies in its depiction of a power struggle. On encountering the text, it is easy to underappreciate Byron’s magnetic innovation by writing off Manfred as a fictionalized account of the poet’s incestuous relationship with his half-sister Augusta Leigh—in keeping with his personal reputation as “mad, bad and dangerous to know.” Upon a closer look, however, it becomes clear that Byron’s dramatic poem is a series of tableaux depicting power struggles between a Byronic hero, Manfred, and a Byronic heroine, Astarte. Continue reading “On First Looking into…Manfred”

Hero Worship, Discipleship, and the Romantic Imagination: On Spivak’s Aesthetic Education

“And so I go, asking the students to enter the 200-year-old idiomaticity of their national language in order to learn the change of mind that is involved in really making the canon change. I follow the conviction that I have always had, that we must displace our masters, rather than pretend to ignore them.” So writes Gayatri Spivak at the conclusion of a chapter entitled “The Double Bind Starts to Kick In” in her recent tome An Aesthetic Education in the Age of Globalization. Is Spivak too, I ask, such a master that we must displace if we are to abide by her own conviction? This is a question I want to pursue as I consider her treatment of British romanticism in this mammoth work. Continue reading “Hero Worship, Discipleship, and the Romantic Imagination: On Spivak’s Aesthetic Education”

Of Mountains and Media: Versions of the Sublime

A few years ago I got a chance to see Marc Handelman’s Archive for a Mountain in person, and it got me thinking about the category of the sublime in a new way. The conceit of the work is straightforward–Handelman assembled into a single book every piece of data he could find about the Untersberg–but the product is impressive. Weighing in at a hefty 740 archival-quality pages of maps, images, brochures, essays, scanned microfilm, screenshots of Wikipedia entries, and more, the book has an excessive materiality of its own. But it also—in the way it inevitably provokes us to imagine even more material that might have been included—foregrounds the incredible constrictions that are necessarily imposed upon any subject in the process of representation, even in those renderings that we are tempted to label exhaustive or comprehensive. Its gesture towards a kind of vast and awe-inspiring archival noumenal that exists beyond the capacity of any single human or technological interface to represent it (as well as its mapping of this limit onto such a traditional representative of sublime Nature) seems distinct to me from other contemporary notions of the sublime, and actually seems to hearken back to the original problematic of the eighteenth-century sublime: how to represent a mountain?

Continue reading “Of Mountains and Media: Versions of the Sublime”