This fall, I’ve been assigned to instruct a class called ‘Introduction to Writing about Literature.’ While the course is designed to transmit a specialized skill-set (textual analysis), it’s not organized around a historical period, event, or philosophical discourse. As an instructor, I’m required to jump around—across periods, genres and continents—in an effort to give students the most comprehensive possible familiarity with literature in English. The only thing that holds the course together is a persistent focus on form and figuration. This is both liberating—it’s great to get close to some of my favorite texts in the classroom–and a little terrifying—unmoored from thematic, historical and philosophical contexts, I’ve found myself wondering if I know anything about how literary language works. In this post, I’ll outline some of the theoretical and pedagogical dilemmas I’ve bumped up against teaching close reading and then explain how I’ve decided to talk about metaphor and figuration in my requirement-level lit course. Though the post turns on my own experiences, I’m hoping that the problems and solutions that I address here may be relevant to readers working out their own ideas about how to teach and test close reading skills.

Continue reading “Teaching Close Reading: Nietzsche, Metaphor and Romantic Poetry”

Elegy in Wordsworth, Turner, and James Bond

As the scene opens, a brief shot catches a spy momentarily transfixed by a painting. That spy is James Bond, and that painting is Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire tugged to her last berth to be broken up, 1838. Soon the as-yet-unidentified Q sits down to offer his barbed reading, and it hits close to home. Stung, Bond refuses to interpret the work of high Romantic elegy that had held his attention moments before—it’s just “a bloody big ship.” This denial is a concession: Bond tacitly admits the painting depicts what Q calls “the inevitability of time.”

Continue reading “Elegy in Wordsworth, Turner, and James Bond”

Dear Mr. Southey, Jump in a Lake: Byron and Epic Humor

There’s a recurring question that springs to mind whenever I sit in the Starbucks in the Barnes & Noble in my little East Texas town and stare up at the mural of authors who all seem to have transcended time and space to have coffee alongside the hipsters: who put Oscar Wilde next to George Eliot, Rudyard Kipling, and Trollope? Seriously, is it any wonder that the man looks so bored? Wilde shouldn’t be surrounded by those Victorian fogies, he should be sipping gin with Truman Capote, Christopher Hitchens, Walt Whitman, and the one man who would almost certainly guarantee a good time, and who also happens to be the focus of this  essay, George Gordon, Lord Byron. The reason for such inclusion is simple: Byron could be an absolutely trenchant satirist when he wanted to be. Byron, like Wilde, Capote or Hitchens, could bring out his own breed of sharp wit whenever someone at a dinner party decided to be cleverer than him, only to be left decimated in a single sentence by his superior rhetorical ability. I know this is a platitude, but sometimes I really wish I could have been a fly on the wall whenever Byron let loose one of those glorious aphorisms that sealed his entrance into the hall of “Truly Spectacular One Liners,” if only to see and understand how it was that Rodney Dangerfield sealed his membership before the poet. (Then again, when you’ve starred in Caddyshack, your “Immortality card” is pretty much secure, unless you’re that blond kid who was the protagonist, and does anybody have any clue what happened to that guy?) Continue reading “Dear Mr. Southey, Jump in a Lake: Byron and Epic Humor”

essay, George Gordon, Lord Byron. The reason for such inclusion is simple: Byron could be an absolutely trenchant satirist when he wanted to be. Byron, like Wilde, Capote or Hitchens, could bring out his own breed of sharp wit whenever someone at a dinner party decided to be cleverer than him, only to be left decimated in a single sentence by his superior rhetorical ability. I know this is a platitude, but sometimes I really wish I could have been a fly on the wall whenever Byron let loose one of those glorious aphorisms that sealed his entrance into the hall of “Truly Spectacular One Liners,” if only to see and understand how it was that Rodney Dangerfield sealed his membership before the poet. (Then again, when you’ve starred in Caddyshack, your “Immortality card” is pretty much secure, unless you’re that blond kid who was the protagonist, and does anybody have any clue what happened to that guy?) Continue reading “Dear Mr. Southey, Jump in a Lake: Byron and Epic Humor”

Review: The Theory of the Sublime from Longinus to Kant by Robert Doran

Any scholar in any discipline with even a passing familiarity with the Romantic era knows how central the idea of the sublime is to Romantic thought. But exactly what is the sublime? The sense of awe and terror that overwhelmed Percy Shelley’s mind and spirit upon first looking at Mont Blanc? Wordsworth’s epiphany of cosmic truth upon his return to Tintern Abbey? Any number of wondrous and terrible events that befell Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner on his adventures? Well, yes and no. For these are merely descriptions of sublime events, and do not in themselves provide any sort of qualitative definition. Before reading Robert Doran’s sweeping and erudite study, I’m not sure I could have answered this question. To be honest, I still don’t know if I can answer it satisfactorily, since by its nature the sublime has a way of both transcending and subverting things. But Robert Doran’s The Theory of the Sublime from Longinus to Kant at least provides a rich and detailed map of the the subject, and even if the map isn’t exactly the territory it’s still invaluable to a scholar of Romantic ideology. Continue reading “Review: The Theory of the Sublime from Longinus to Kant by Robert Doran”

Any scholar in any discipline with even a passing familiarity with the Romantic era knows how central the idea of the sublime is to Romantic thought. But exactly what is the sublime? The sense of awe and terror that overwhelmed Percy Shelley’s mind and spirit upon first looking at Mont Blanc? Wordsworth’s epiphany of cosmic truth upon his return to Tintern Abbey? Any number of wondrous and terrible events that befell Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner on his adventures? Well, yes and no. For these are merely descriptions of sublime events, and do not in themselves provide any sort of qualitative definition. Before reading Robert Doran’s sweeping and erudite study, I’m not sure I could have answered this question. To be honest, I still don’t know if I can answer it satisfactorily, since by its nature the sublime has a way of both transcending and subverting things. But Robert Doran’s The Theory of the Sublime from Longinus to Kant at least provides a rich and detailed map of the the subject, and even if the map isn’t exactly the territory it’s still invaluable to a scholar of Romantic ideology. Continue reading “Review: The Theory of the Sublime from Longinus to Kant by Robert Doran”

Juvenilia: The Syllabus!

I’ve been musing for a while about how much fun it would be to organize a class for undergraduates centered around the theme of creative writing by youthful authors. Perhaps because of the Romantic association between individuality, genius, and youth (an idea that persists in present-day cultures of information technology), 18th- and 19th-century literature is wonderfully full of examples of juvenile authorship. In this post, I’ll just name a few examples of texts that might pair well together in a class on juvenilia in the 18th and 19th centuries, with special focus on the Romantic period. I’d welcome the additional suggestions of readers! Continue reading “Juvenilia: The Syllabus!”

John Clare, Biopoetics, and the Romantic Lyric

When I read the blurb for Sara Guyer’s book Reading with John Clare: Biopoetics, Sovereignty, Romanticism in the NASSR bulletin this past July, I felt both fascinated and puzzled. What could Romantic lyric poetry possibly have to do with biopower and its institutional controls? What constitutes a “biopoetics”? A few months have passed and I’ve finally found the time to ask these questions of the book itself, which I’ve found to be a challenging, but ultimately rewarding, read. In this post, I’ll share some insights I’ve gleaned from Reading with John Clare–insights about Clare’s poetry but also about Romantic aesthetics and its legacies more generally.

Continue reading “John Clare, Biopoetics, and the Romantic Lyric”

The Climate of Romanticism: Autumn in Paris 2015

Fall has always been my favorite season. The excitement and energy of a new academic year, with the promise and potential for new experiences, engagements, commitments and ideas never ceases to amaze me. I’ve experienced this to be especially true this fall. Felicitously, and making good on Devoney Looser’s advice regarding applying for fellowships, published on this blog, I received a fellowship to take part in Northwestern’s Paris Program in Critical Theory, a graduate exchange program with the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle. In the Program, you spend the autumn in a seminar covering a select topic in critical theory (this year, belief in Jacques Derrida’s “Faith and Knowledge”) led by Samuel Weber, best known as a theorist, scholar of media, and translator of Derrida and Theodor Adorno. For the rest of the year, you are free to engage in archival research and dissertation writing, and to take part in European academic life. I’ve included a link to the program’s website, since it is open to all graduate students with external funding. With annual graduate fellowships available at most universities in the form of presidential fellowships and other awards that don’t require full-time residence at the home university, in addition to important external awards to apply for, such as the Fulbright program, ACLS/Mellon Dissertation Completion Fellowship, the Chateaubriand Fellowship in the Humanities, and many more, numerous great possibilities exist for grads across the humanities and social sciences to take part in the Paris Program in Critical Theory.

Specifically, I’m in Paris this year for two reasons. First, I’m here to study contemporary French environmental theory as I develop the conceptual framework that’ll drive my dissertation on Blake and ecological politics. Consequently, over the coming months on the blog, expect reading lists and book reviews of the latest in European social thought, with an emphasis on texts that haven’t been translated into English that I imagine will be especially relevant to graduate students generally, and Romanticists especially. There’s also nothing like having an audience to focus and sharpen the mind with language learning, translation, and writing, right?

Yet, this year–as I’m sure most of our readers are already aware–is an especially significant one for climate politics, decades in the making for climate policy experts and negotiators, and centuries in the making, with respect to the conditions those most optimistic among us hope will begin to be overturned: the massive amounts of carbon accruing in the earth’s atmosphere. In December, the United Nations Climate Change Conference (also known as the COP21) will convene in Paris, with the hope of establishing a legally binding universal agreement to begin curtailing carbon emissions. The goal is ultimately to limit the amount of atmospheric carbon to that which will produce no more than a 2°C rise, on average, above pre-industrial levels. So second, and relatedly, my fellowship is geared to support my hope to help document the important visual culture that looks to emerge around the the climate conference. Already, there are prominent stirrings–with the ArtCOP21 cultural festival set to convene in Paris, and across the globe, paralleling the climate summit. All of this, I believe, retains certain implications for the study of Romanticism.

Continue reading “The Climate of Romanticism: Autumn in Paris 2015”

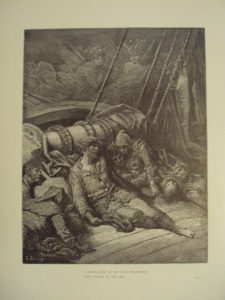

Of Images, Sublime, and the Necessity of Keeping Crossbows Off Ships

It’s probably not a good first impression upon my new reader to admit that I did not actually re-read The Rime of the Ancient Mariner before I began this first post. I promise it was not out of apathy or laziness. You see, I’ve read the Mariner’s Tale at least ten times in my life, at least four times for school, the other times because my

It’s probably not a good first impression upon my new reader to admit that I did not actually re-read The Rime of the Ancient Mariner before I began this first post. I promise it was not out of apathy or laziness. You see, I’ve read the Mariner’s Tale at least ten times in my life, at least four times for school, the other times because my

teachers had instilled in me the beauty and power found within this strange and wonderful poem. This confidence in the material, really my own working knowledge of the poem, allows me to focus instead upon a work of art that has played a significant role in my appreciation of the work. Continue reading “Of Images, Sublime, and the Necessity of Keeping Crossbows Off Ships”

Reading Romanticism Today (A Pedagogical Experiment)

By Talia Vestri

The title of this week’s post echoes the title of my newest course, which I’m currently three weeks into teaching. “Reading Romanticism Today” is one of the English department’s introductory courses advertised as “Freshmen Seminars in Literature.” These classes satisfy our College of Arts and Sciences’ first-year composition requirement.

Having taught several of these intro-level seminars in both the English and Writing Program departments, I’ve designed courses on poetry, fiction, and contemporary media. I typically organize the syllabus around a particular theme, like “the modern American family” or “poetry of the self.” I have not yet focused one on any particular historical period. But since this was likely to be one of the last courses I’ll teach while still a doctoral student, I wanted to develop a syllabus that not only falls within my field of research, but that also pushes beyond a straightforward poetry survey. Continue reading “Reading Romanticism Today (A Pedagogical Experiment)”

Behind the Scenes: Editing "Studies in Romanticism"

By Talia Vestri

Back in June, I posted some rambling reflections about my current position as Editorial Assistant with Studies in Romanticism. Over the summer, I had the pleasure of communicating with SiR’s current Editor, Charles Rzepka, about his own experiences and expectations with publishing the journal. I asked him to provide N-GSC Blog readers with some insights into the journal’s submission process, editorial decisions, and the dreaded reader evaluations. Here, I offer you some highlights from our conversation:

Continue reading “Behind the Scenes: Editing "Studies in Romanticism"”