William Paley’s Natural Theology (1802) was a profoundly influential distillation of what was then known as the argument from design, and is now called intelligent design. Observing a profoundly functional world around him, Paley claimed that “in the properties of relation to a purpose, subserviency to an use, [the works of nature] resemble what intelligence and design are constantly producing, and what nothing except intelligence and design ever produce” (216). Paley’s God is a master tinkerer, less omnipotent immensity than systematic, clever craftsman. Everywhere he turns his argumentative lens (the eye, after all, being Paley’s chief example), he finds a natural world that works. Functionality proves design, design indexes a designer, and a designer must design consciously, with specific ends in mind. The divine idea is realized in the created world through the careful accretion of contrivance. This is Paley’s word: God as the great contriver, with an exquisite design sensibility. Final cause predominates, as everything is shaped by divine purpose toward its end.

Continue reading “Unintelligent Design: Keats, Natural Religion, and Reproduction”

"The world’s first instant mashed potato factory," and other Romantic-era food innovations

As a lover of anecdotes in a field (English) that doesn’t always embrace them in its scholarship, I often come upon delightful details I want to share, but can’t—in my dissertation, at least. So, it makes me especially happy to have the opportunity to write for this blog, as I get the chance to relate all the fun facts I’ve been learning in my food studies-related reading. Today, I’m expanding from my previously England-centric scope to delve into E.C. Spary’s recent book Feeding France: New Sciences of Food, 1760–1815. Continue reading “"The world’s first instant mashed potato factory," and other Romantic-era food innovations”

Continue reading “"The world’s first instant mashed potato factory," and other Romantic-era food innovations”

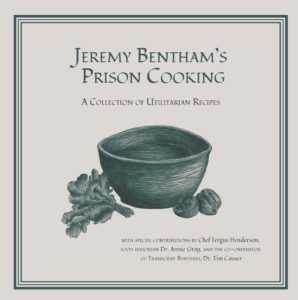

Panopticon Palate

Like it or not, 2016 is fast approaching, along with a return to all the responsibilities grad school entails. Perhaps you’re surveying the last few weeks of financial and dietary excess (and work backload) that the holiday season seems to demand with a feeling of regret and rising panic. If that’s the case, then I have just the book for you: Jeremy Bentham’s Prison Cooking: A Collection of Utilitarian Recipes!

Continue reading “Panopticon Palate”

Ancient Pedigrees, Old Trees and Numinous Rocks

In Edmund Burke’s attack on the “metaphysic rights” (152) of men that inspired the French Revolution, he urged Britons to look to their “breasts” rather than their “inventions” for the source of liberty. Burke deployed the language of sensibility to naturalize a political system organized around the idea of heredity. The argument goes that inheritance binds English citizens to their constitution with the instinctive force of a bond of kinship. But Burke has to admit that the awe-inspiring aspects of the state –its “pedigree and illustrating ancestors” (121)—are just so many “pleasing illusions” that make “power gentle, and obedience liberal” (171). Psychologically, however, Britons need these institutions because they have so thoroughly internalized the principles that they represent that those principles have become second nature. What keeps property and political representation in the hands of the few is what ties Britons to a shared past and future. Burke’s logic would be like Foucault’s if Foucault had wanted to celebrate the panopticon. Continue reading “Ancient Pedigrees, Old Trees and Numinous Rocks”

A Bird’s Song, and Two Men Divided by Death, United by Age

It’s nearing the end of the year, finals are over, papers are due, but we’re literature majors here, so of course the only thing that matters is the symbolism of winter. The year is dying and ready to sleep forevermore — bringing in its death a spark of new life, new possibilities, and the mass cultural/capitalistic orgy that is the Christmas season. Parting with the cynicism, however, I decided that rather than construct coherent argument, I would instead remember a moment from one of my Romanticism courses and muse on the experience. Continue reading “A Bird’s Song, and Two Men Divided by Death, United by Age”

It’s nearing the end of the year, finals are over, papers are due, but we’re literature majors here, so of course the only thing that matters is the symbolism of winter. The year is dying and ready to sleep forevermore — bringing in its death a spark of new life, new possibilities, and the mass cultural/capitalistic orgy that is the Christmas season. Parting with the cynicism, however, I decided that rather than construct coherent argument, I would instead remember a moment from one of my Romanticism courses and muse on the experience. Continue reading “A Bird’s Song, and Two Men Divided by Death, United by Age”

The Story of Death

In its “List of Deaths for the Year 1750,” the Gentleman’s Magazine included one

Mrs Reed of Kentish Town, aged 81. She had kept a mahogany coffin and shroud by her 6 years, when thinking she should not soon have occasion for them she sold them, and dy’d suddenly the same evening. (188)

There’s an elaborate art of dying premised here. We can start with the articles of burial, at the ready, signaling Mrs. Reed’s vigilant preparation. Coffin and shroud are inmates, given the privilege of domestic intimacy, and death too will arrive like an intimate relation returning home. By disposing of the accoutrements of burial, Mrs. Reed presumed she would live. The unstated conclusion: her lapse in preparation invited the very thing she had ceased to fear. And it caught her, cruelly, without the benefit of last rites. (As Philippe Ariés explains, it is only recently that we have come to desire a quick death.) Death may be unknowable, but it seems to have an eye for formal irony and narrative resolution. Where we nod, it comes winking.

Continue reading “The Story of Death”

Charles Dickens vs. Leigh Hunt: Charity, Social Reform, and the Problem of Hell

My sister and I have two very important holiday traditions: 1) we always go to a haunted corn maze before Halloween, and 2) we always watch The Muppet Christmas Carol before Christmas. We don’t often admit to the second tradition (and when we do, we kind of pretend that we only enjoy the Muppets “ironically”), but it’s something we’ve done for as long as I can remember. It just doesn’t feel like Christmas until Katie and I are sitting on the couch, singing along to the song “Marley and Marley” while two enchained muppet ghosts rattle around the TV screen, bemoaning their eternal punishment.

Continue reading “Charles Dickens vs. Leigh Hunt: Charity, Social Reform, and the Problem of Hell”

In the shadows: memories of childhood, memories of identity

For some strange reason, I was always drawn to the mysterious topic of film in my country, Croatia, and the neighbouring countries whose story of different cultures intertwined at some point in history. I used to watch a lot of films while I was growing up, but I have never actually considered them as being that interesting, or multi-layered, with a hidden message crawling under the main storyline of a film, probably because of the themes that explored the problems of social significance through a representation of violence, for example, or comedies that came out after the war period in Croatia, dealing with memories and consequences of it, and the fact that I was too young at the time. But that changed rapidly. I grew up, and started to see the world around me in a different way, while struggling with the grim reality of a young person with so many hopes and dreams to be cut off and put down by the political and social situation in the country I lived in. More and more I realized that the topic of identity and the crisis of the same is becoming a vital part of my research, as well as my own existence. A lot of people have asked me why film then, and horror film of all genres, to explore identity, and the more people asked me that, the more I thought that I chose precisely the right medium for my research. Continue reading “In the shadows: memories of childhood, memories of identity”

Coleridge's Imagination through the lens of J. R. R. Tolkien

As a writer of fantasy, J. R. R. Tolkien hardly needs an introduction. Even before the success of the film adaptations of his work turned Tolkien into a household name, he had won first the hearts of children with The Hobbit in 1937 and, some twenty years later, the hearts and minds of adult readers with The Lord of the Rings. But, like Coleridge and MacDonald before him, Tolkien thought deeply about his craft as a writer and creator, and it is by largely virtue of this thought that his art has achieved such timeless success. His 1939 lecture “On Fairy-Stories,” subsequently published as an essay in the 1964 book Tree and Leaf, is, as the editors of the recent authoritative edition of the essay put it, “Tolkien’s defining study of and the centre-point in his thinking about the genre (of fantasy), as well as being the theoretical basis for his fiction” (Flinger and Anderson 9). In this seminal work, he addresses all the points about the imagination raised by Coleridge and, following the Victorian writer George MacDonald, defends their application in the literary arts. Continue reading “Coleridge's Imagination through the lens of J. R. R. Tolkien”

As a writer of fantasy, J. R. R. Tolkien hardly needs an introduction. Even before the success of the film adaptations of his work turned Tolkien into a household name, he had won first the hearts of children with The Hobbit in 1937 and, some twenty years later, the hearts and minds of adult readers with The Lord of the Rings. But, like Coleridge and MacDonald before him, Tolkien thought deeply about his craft as a writer and creator, and it is by largely virtue of this thought that his art has achieved such timeless success. His 1939 lecture “On Fairy-Stories,” subsequently published as an essay in the 1964 book Tree and Leaf, is, as the editors of the recent authoritative edition of the essay put it, “Tolkien’s defining study of and the centre-point in his thinking about the genre (of fantasy), as well as being the theoretical basis for his fiction” (Flinger and Anderson 9). In this seminal work, he addresses all the points about the imagination raised by Coleridge and, following the Victorian writer George MacDonald, defends their application in the literary arts. Continue reading “Coleridge's Imagination through the lens of J. R. R. Tolkien”

Felicia Hemans and the Brow

Felicia Hemans is doubtless one of the most important writers of the early nineteenth century. Yet one of her signal achievements remains, to my knowledge, unremarked: Hemans is the most committed and innovative practitioner of the poetics of the brow. To wit, observe the doomed Antony at his last supper.

Continue reading “Felicia Hemans and the Brow”