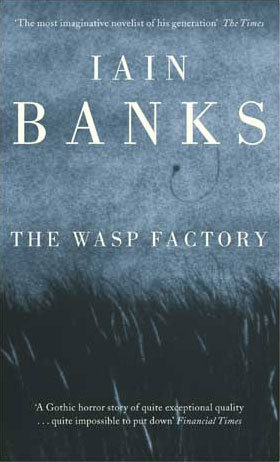

In the past week, dozens of tributes to Scottish writer Iain Banks, have appeared online— hundreds, if you count the smaller, no less poignant, expressions of grief and thanks via social media. Banks died of cancer on June 9th, two months after releasing a statement to his readers announcing his illness and the devastating news of his short life expectancy. Publishing consistently since the early 80s, he leaves behind a significant body of work, including both general fiction and science fiction under the name Iain M. Banks. Though we were “prepared,” the loss hits his fans hard and sooner than expected. Here is my tribute to this Great writer, one that I feel both unqualified and strongly compelled to write. Banks is certainly not a Romantic writer, so it may seem strange for me to write about him here. I discovered his novels only within the past few years, and I’ve still only read a handful of them. Yet, these works have made a lasting impression on me and, more to the point of this post, on my classroom, often paired with Romantic texts.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein has been analyzed and interpreted in many different contexts, providing endless possible readings and uses. For some students, the possibilities are exciting, but, for others, they are also overwhelming. Frankenstein is one of the most teachable Romantic novels for the college classroom, but it can be difficult to convince students not accustomed to reading nineteenth-century texts (or not used to reading much in general) to have the patience to tread through unfamiliar prose styles in order to appreciate the novel’s worth. I think I can assume that many of us have taught this novel and had this experience at some point. There are many strategies to prepare students for the foreignness of earlier texts, but one that I frequently use is to pair a Romantic novel with a more contemporary novel. Twice, I have taught Frankenstein with Iain Banks’s The Wasp Factory (1984) in my freshman literature and composition classroom, a combination that exposes students to two types of literature: both qualify as Gothic, but we see it from two very different time periods and styles. After a week or so of feeling their way through Frankenstein, keeping characters straight and starting to construct understandings of settings and major themes, students develop a tenuous relationship with the text. Then I introduce them to a character named Frank.

“I represent a crime…” (10).

The Wasp Factory tells the story of this disturbed, sixteen-year-old, first-person narrator and his daily routines as he recounts his experiments and murders (that’s right, murders) on his family’s isolated Scottish land. His father, himself a reclusive mad scientist of sorts, has been seminal in Frank’s unstable (my students use the word “insane”) character. Frank, a god in his domain, spends his time fabricating and performing private rituals involving small animals and insects, creatures whose lives and deaths Frank orchestrates in order to tell the future or reinforce his surveillance and control over his island. The crowning glory of these devises is, of course, the wasp factory, a machine constructed from a giant clock face that holds twelve possible deaths for the wasp Frank releases into it. The death chosen by the wasp holds a wealth of information for our narrator. Frank is a powerless character desperate for power, abandoned by his mother and brother. Sound familiar? Frank, despite his age, has killed three times, and the twist ending blows my students’ minds.

“My dead sentries, those extensions of me which came under my power through the simple but ultimate surrender of death, sensed nothing to harm me or the island” (19).

Following up Frankenstein with The Wasp Factory solidifies students’ understandings of both novels by comparing and contrasting. Both texts are inherently about the construction of monstrosity on different levels, as well as human agency in matters of life and death. The creature and Frank are both considered to be monstrous outsiders for their behavior and appearances, but both have also been “created” by their father figures, practically devoid of any female influence. They are not unlike Victor in this sense, as well. They generate power through manipulation of their limited resources with conventionally inacceptable (again, “insane”), behaviors. All three construct their own forms of justice and morality based on adversity, environment, self-delusion, and a striving for power. The students compare and contrast these elements with little prompting from me as Frank and his world accentuate the choices and characteristics of Victor Frankenstein and his creation, not to mention the common themes of nature, science, motherhood, destruction, revenge, madness, etc.

“The factory said something about fire” (23).

The Wasp Factory is not a Romantic text, and that is what makes it so useful in this context: accessible and entertaining, it acts as a stepping stone between the students’ own interests and experiences and those of the early nineteenth century. Students have told me that The Wasp Factory is “the first book I’ve read that has actually made me think.” Another student became so fascinated with the spatial descriptions of Frank’s island that he went out and found a map of the book online, then did the same for Frankenstein. Banks’s novel is incredibly visual, and students want to visualize other texts just as clearly. They squirm at the more graphic, gruesome parts in the novel, but they can’t stop talking about them. The book complicates their own assumptions regarding characters as likable/unlikable and right/wrong and what those judgments are based on. They find Frank frightening and (again) “insane,” yet develop such an affection for him, one that they find themselves extending to the Creature and even to Victor. Writing about both texts together, they explore the complexity of character motives. They learned that liking a character does not mean that they can trust him, and that brings them even closer to that character.

“The wasp factory is beautiful and deadly and perfect” (154).

The strangeness of Banks’s novel, set in a familiar time and told with accessible and beautiful language, opens up a door to welcome other types of strangeness into the classroom, even a strangeness going back almost 200 years. A monster and his creations are always in good company. Iain Banks, thank you for your monsters and your creations. They will continue to teach us so much, not least to enjoy brilliant and important literature.

Banks, Iain. The Wasp Factory. 25th Anniversary Edition. London: Abacus, 2009.