Greetings from the Valley of the Sun and happy 2014! The Colloquium extends its warmish wishes to everyone, especially those who were (and are again) in the path of the Polar Vortex. We hope you are all doing okay in what sounds like very challenging weather. Our weather here is mild, in fact it is too mild, uncannily mild. So, while the West Coast might not be suffering the chill I’d be willing to bet this summer will be destructively hot and dry for us, especially the southwestern states, unfortunately.

Off the (depressing) topic of weather, I hope to bring some of the discussion the colloquium had this past week to you all. At our meeting we examined a few book chapters. Specifically, Chapter 13, “The Age of the Novel,” from The History of British Publishing by John Feather. And also the Interlude Chapter, “Necromanticism and Romantic Authorship,” from Necromanticism: Traveling to Meet the Dead by Paul Westover. And also we had a brief digression on Sherlock Holmes (as you do) which is where we will start.

Perhaps unsurprisingly most of the colloquium is fan of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s character, and the various current iterations such as Elementary and Sherlock. And some of us have seen the PBS documentary “How Sherlock Changed the World” [http://www.pbs.org/program/sherlock-changed-world/]. This documentary, which is trying to channel some of the popular enthusiasm into historical knowledge, roughly claims that Doyle’s character impacted forensic science more than any actual forensic scientist. The argument demonstrates innovations from the stories and then discusses the way Sherlock Holmes inspired people to become forensic scientists in the latter half of the 20th century (and these people use knowledge they derived from or that was inspired by Holmes).

You all will have to watch the documentary yourself, but we were not especially impressed. Perhaps the error that was the gravest was that the documentary never talks to literary historians or any cultural historians. Mainly they use current forensic scientists with a smattering of evidence from the stories. The one speaker that was related in some way to the literature was a writer of popular fiction who had also written a few novels using the Sherlock Holmes character. None of us thought that these people were ‘bad’ speakers per se, but were somewhat miffed that a documentary that focused on the influences of literary character on history did not talk with researchers who dedicate their time and energy to understanding that relationship. More than anything this method seemed to be merely a data point in the larger question of the role of the humanities in the public sphere. PBS, one would guess, is no doubt a largely sympathetic audience when it comes to the humanities. But, at least in this case, the humanities researchers were largely left out of a discussion on humanities; a troubling situation to say the least.

One of the other problems was the surprisingly graphic nature of the documentary, where they used actual crime scene photographs. The one that we found the most disturbing was of Marilyn Reese Sheppard. She was bludgeoned to death on July 4th of 1954. The documentary used a photo of her, uncensored with all the physical manifestations of violence, the gore, visible in stark black and white. But, the show did go to the effort of censoring her exposed nipple. (As an aside, someone else might have edited the photo before, then the show used it, but it still seems an odd choice). Whatever the case maybe, the use of these photos definitely raised questions of violence and bodies: what bodies can and cannot be displayed doing or being and how violence is received by the larger audience.

As you can see this innocuous documentary raised some perplexing conundrums for us: how we portray violence to bodies and whether the humanities needs to try and be more aggressive with its public face.

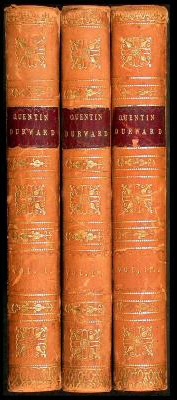

Eventually, though, we turned to the articles which dominated the majority of our meeting. We started with John Feather’s work, which provoked a question about research: how we (scholars) read and whether that should or should not be like the way the text was read (or at least as close as possible). According to Feather novels in the romantic period, especially post Waverly by Scott, were published in the popular ‘Triple-Decker’ format (Feather 144), for a variety of reasons, but mainly because it meant that the publisher got to sell the novel three times (Feather 147); arguably it also made it better for the lending libraries because three people could be reading the ‘same’ book at one time. But, especially as graduate students, we do not typically read works like Waverly in three volumes over a period of months; we have maybe a week (or two) to devour the book while also reading one or two other books (plus a variety of other work and research). This is not to say that the system needs to change, but we were wondering what it means for us as researchers and the arguments that we make that we do not read the novels in the same way that they were historically. This discrepancy increases in the Victorian period with serialization: many readers read chapters from magazines while presumably fewer read the novels as one unified whole (due to the cost of the unified novels). We were unsure whether this mattered at all: does reading one way or another dramatically influence one’s reception of a novel? Especially considering the periods people had time to discuss the developing plot with each other, after a household had finished the first volume of a work and how that might change their perception. Should we strive to read as the people did, so that our claims are more ‘accurate’ or is accuracy merely a facade because meaning does not change that much between varieties of reading?

There was one statement that generated a great deal of discussion. At the very end of the chapter, Feather claims that “there was a brief period in the middle of the nineteenth century when literary merit and popular success coincided” (Feather 152). Most of us agreed that this statement did not seem to fit well with the rest of the chapter and that the statement was worrisome. For example, the conversation drifted over to the idea of the Romantic Canon, i.e. the big six of Blake, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Byron, Shelley, and Keats. For a long time those six (and sometimes only really five) have been the writers of ‘literary merit’ at the exclusion of other sexes, races, classes, forms, genres, and so on. Thus, we thought that the particular statement was obscuring a few other important discussions. But the idea of ‘literary merit’ also drew out another question: what are English Scholars? Are we art critics? Are we cultural historians? Are we theoreticians and philosophers? Are we all things or none? There were good arguments for all positions, well except ‘none’ no one argued for that, nevertheless we debated for a bit. I apologize for all the questions, and especially our lack of concrete answers, but we pondered that particular idea for a while with no particular conclusion.

At that point it seemed wise to switch over to Paul Westover’s chapter before we lost our entire weekend to the previous question(s). Westover argues that even if an author is living, especially the Romantic authors, because of their literary success they become ‘dead’ (Westover 93). Somehow the author becomes both dead and alive, which is obvious in the various descriptions that Westover cites. For example, people would visit William Wordsworth but ultimately be surprised because the being they encountered did not match up with their vision thus they would exclude the material body from their vision and description, and so as Westover states “Wordsworth had become an artifact and a ghost in his own house” (Westover 95). In part this un-dead-ness appears to result from the disconnect between the image of the author in the reader’s head and the material reality of the author. Perhaps most interesting to us was the focus on the author. Everyone is aware, of course, that the Author died a couple of decades ago and that we do not talk about them. But, Westover’s book is in part about authors and their existence. Humor aside it certainly does not seem like a poor trend for literary scholars to also incorporate the author into their analysis but obviously the author cannot be overriding because texts live apart (as Westover and others show) from their creators.

That did lead to one concern: are we as scholars also victims idolizers of authors? And if so, might that impact our ability to be clear-eyed when making arguments? Or, phrased another way with a greater focus on undeath: if you could resurrect an author and speak with them would you / should you? While a few names were thrown out for ‘yes’ to resurrection (like Mary Shelley) and ‘no’ (like Edgar Allan Poe), we decided that the literary scholar’s enthusiasm for certain authors was probably a good feature because it allows us to keep going even when we encounter research dead-ends and conundrums. Although, being on guard against over idolization of course is never a bad idea.

Anyway, these are a few of the items that we discussed. If there is anything you would like to add in the comments, please do! Otherwise, good luck with your work in 2014 and we look forward to many exciting discussions as inspired by this graduate caucus!

Kent Linthicum

Quarterly Editor's Note: Collaboration & The Rush of New Insights

From one of the colder sites of the “Polar Vortex 2014,” I write to wish everyone within the orbit of romanticism (and beyond) a very happy, healthy, and successful New Year. The concluding months of 2013 brought with it the installation of a highly engaged and innovative new cadre of writers, with established authors Aaron Ottinger and newly elected NGSC Co-chair Laura Kremmel continuing to publish on the blog, making the autumn season an incredibly exciting one. There were no fewer than sixteen pieces generated in the better part of the last three months of the year. Writers explored a range of topics from the formation of scholarly collectivities, the importance of self-reflexivity regarding the possibilities and limits of reading practices, to new imaginings of cross-disciplinary approaches to romantic literature. An immediate and special congratulations goes out, as well, to blogger Renee Harris, who was selected to present new work at the Keats Foundation Conference, “Keats and His Circle,” at the Hampstead House this spring.

In my first editor’s note, posted in October, I made the proposition that this blog comprises a space where the “rush of new insights” might be most immediately felt (especially with respect to the sharing of concepts driving work-in-progress). This was most certainly the case across the autumn’s trajectory. In what follows, I highlight what I found to be some of the more interesting and important new threads of inquiry that appeared in the last few months. I’ll also make some suggestions regarding what is to be expected going forward, into 2014.

Deven Parker’s introductory piece “Towards a Tangible Romanticism” holds out the promise of very important work to come. In it, Deven outlines a new resolutely materialist approach to the interpretation of Romantic culture based on what she critically terms “an archaeological hermeneutics.” Taking a disciplinary point of origin in Deven’s initial undergraduate training in archaeology at Penn, the proposed method pivots, as Deven puts it, on the notion that a book retains “a relation to all other objects of the same type” with strata of meaning retaining the potential to be excavated on the basis of things like choice of verse. This comes in comparative relation to other literary texts, but with a vocabulary that significantly breaks from well-worn tropes and idioms in literary studies, with the result that books come into view as simultaneously “local and transhistorical artifacts.” At its core, Deven’s method—as it seems to me—offers myriad illuminating directions for shifts in focus and understandings of relations that comprise the materiality and conditions through which the texts and objects we study are generated, received, used, and redeployed.

Arden Hegele’s November blog publication—“Romantic Geologies and Post-Organic Forms”—represents some of the very best new thinking I’ve encountered as of late. Her ability to collegially engage with, and synthesize, work by the caucus graduate authors was as enlightening as it was inspiring. By highlighting the “fundamental” as a core concept connecting the blogging being undertaken by other caucus members, Arden brings out the ways in which our group is returning to the cornerstone issues upon which Romantic studies is constructed—and it is this thread that I hope other authors will continue to draw out over the next year. Arden directs our attention to vexing questions so often taken for granted: what represent the fundamental principles with which we define the scope and body of materials we study? What are the methods we use to pursue this, and what are the temporal and theoretical limits and possibilities for Romantic studies, with respect to the nineteenth-century and beyond? Arden’s pointing to geology was crucial in this regard—and her luminous turn to look at the ways the “instability of Romantic geology shook the foundations of the period’s poetry” generates a vital potentiality of thought. Just as well, I was grateful for Arden’s bringing genre into our continuing conversation on the blog—in a reading of Group Phi, whose writing on the topic as both “sedimented” and “metamorphic” Arden nicely highlights. I was especially compelled by the way Arden amplified the importance of Phi’s theorization, arguing that thinking about genre in geological terms endows the interpretive act with a particular urgency given the politics of our own contemporary moment. It’s connected, as Arden so memorably contends, with “the ethics of geotechnical excavation, and particularly the problem of violently appropriating formerly organic structures, now metamorphosed into inorganic matter (oil).”

More recently, Nicole Geary and myself, in conversation with Arden, took this thinking as a point of departure for considering how the field of geology represents a rich zone for thinking through our own respective practices—artistic, literary, and art-historical. This led to the first collectively written post on the blog, with the broader purpose of exploring the relation between romanticism and contemporary visual culture. Ultimately, it is my wish that multiple authors collaborate in the new NGSC “Dialogues” series to produce one jointly-written post per quarter.

Further, on the collaborative front, we saw three illuminating posts by different authors belonging to the Arizona State University 19th-C Colloquium. In their first piece, Kent Linthicum spoke to not only how their scholarly collective was formed, but also to the logic defining its practices, which hinges upon an ever-present “focus on professionalization.” It struck me that this is precisely what the caucus community is doing as well, and am convinced of the importance of getting clearer on precisely what professionalism and the process of becoming professional means within the context of our field. Also, on the point of collaboration, and interdisciplinary on another axis, Jennifer Leeds published her recent interview with the political scientist and author of Jane Austen, Game Theorist Michael Chwe in December. Jennifer and Professor Chwe’s discussion proves absolutely exemplary for locating the ways in which texts produced by a figure on which many of us work can represent a field through which we might re-think a range of issues at the nexus of different disciplinary frameworks, practices, and values. This, of course, is to say nothing of the brilliance with which Jennifer approached the interview, bringing into play her own crucial investments with respect to gender and the challenging of heteronormativity on the basis of the pervasive configuring force of homo-social and –sexual relations in the nineteenth-century novel. Jennifer’s including these concepts in the interview yielded highly productive results, which I found thrilling.

In short, I am pleased that the state of the Romantic studies blog(e)sphere is very strong entering 2014—and I enthusiastically look forward to reading the critical mass of writing that will appear in this forum in the coming months.

NGSC E-Roundtable: Romanticism & Geology

Introduction: This piece comprises the first of a series of interdisciplinary dialogues that will appear quarterly on the NGSC Blog. The initial iteration finds NGSC contributing writers Arden Hegele, Jacob Leveton, and artist in residence Nicole Geary engaging with geology as a factor in the production both of Romantic poetry and contemporary sculpture. Towards this end, they collectively looked at a range of geologically oriented literary texts (Felicia Hemans’s “The Rock of Cader Idris,” Charlotte Smith’s “Beachy Head,” and Percy Shelley’s “Mont Blanc”), works by the visual artists Robert Smithson and Blane de St. Croix, and literary, art-historical, and ecological criticism. Arden, Jacob, and Nicole then posed a series of questions for, and responded to, one another in a discussion that pivots upon a set of shared aesthetic problems and conceptual issues linking current critical and contemporary creative practices.

Roundtable:

Arden: On the subject of the nonhuman voice in Nature, in “Mont Blanc,” Shelley writes that the mountain’s “voice” is “not understood / By all, but which the wise, and great, and good / Interpret, or make felt, or deeply feel” (80-83). How do you see Shelley’s mountain’s form in relation to poetic form, or, how might you relate the challenge of geological interpretation to the interpretation of Romantic literature?

Jacob: This is a great question with which to lead off, and I think provides an effective frame to derive some important points regarding the relation between Shelley’s poetry and politics. Of course, the lines to which you’ve directed my attention drive toward some of the liberatory aspects of Shelley’s poetic project at the time. The poet addresses Mont Blanc and posits that,“Thou hast a voice, great mountain, to repeal / Large codes of fraud and woe; not understood by all, but which the wise, and great, and good / interpret, or make felt, or deeply feel” (80-83). The lines advance the point that Mont Blanc as a nonhuman geological form retains a voice to speak. That voice is comprehended by the “wise, and great, and good” who experience the mountain’s affective force at a high level of intensity (to “deeply feel”). Such a knowing-subject, indeed the Shelleyan poet, interprets the mountain’s geological form and communicates it in a way that effectively manifests itself as a field of social-critical potentiality. What I mean by this is that the poetic engagement with Mont Blanc, that itself generates the poem’s form, is geared to be mobilized in challenging and overturning social inequities. The poetic form that Shelley’s “Mont Blanc” makes available is one that takes geological interpretation as a point of departure for the purpose of social critique, and so relates to broader issues regarding interpretations of Romantic literature informed by historical-materialist theoretical investments, and the field of poetry and politics, more generally.

Nicole: Jacob, “Mont Blanc” seems to be written with a lonely and inhuman aura, one that puts nature out of the grasp of humankind. Do you agree that, as Heringman writes, it helped “mobilize the analogy between geological and political revolution” (13-14)?

Jacob: Your question is a wonderful one, as well–and, actually, while I’d agree that “Mont Blanc” is written with a profoundly inhuman aura I’m convinced it’s one that encodes a form of revelry in the nonhuman other. Ever since my first time working with that particular text, I’ve found it to offer a particularly energetic intellectual jouissance in its impellation that the reader recognize a significant interconnectivity with the natural environment. In this regard, the natural environment can be seen as deeply other and simultaneously co-constitutive of a self that is connected with all other sentient and non-sentient beings. This is why I found Heringman’s remarks so persuasive, with respect to how the “Romantic recognition of the earth’s unpredictability and difference from human interests” ultimately “permits progressive analogies to human agency” (13). One valuable concept the movement to posthumanism gives us (though one which the field of late eighteenth-century cultural production makes possible, by way of writers like Rousseau, Joseph Ritson, Erasmus Darwin, and others) is that the world in which we find ourselves is comprised of a rich myriad of human and nonhuman life and that to understand what it is to be human it is at once necessary to understand what it is to be human in relation to nonhuman life, the natural environment, and non-sentient matter. Geologically, it is the non-sentience of the mountainscape that Shelley’s poem engages with the utmost force, and its that difference between the human poet and nonhuman natural/geological phenomena that drives the poem. This is what I believe that poet is getting at when crafting the image of “The everlasting universe of things” which “Flows through the mind, and rolls its rapid waves” (1-2). The poetic metaphor is taken from the Arve as the river that cuts through the ravine where the poet is positioned, with geological processes here comprising the primary factor of Shelley’s poetic production. Nonhuman geological and human subjectivities are differentiated, yet come together within the poem’s form as a zone of human/nonhuman environmental contact. They’re connected as Shelley’s poem draws out a vector of signification that links the Arve as an example of a formative geological agent that continually carves the mountainscape, the poet’s consciousness in writing, and the reader’s subjectivity in reading. These notions advance Heringman’s argument quite well. If geological formations like Mont Blanc make visible the way in which the earth is in a continual state of transformation–and it’s a given that species do best when they are adaptable to change and humans constitute one species position within a broader web of nonhuman life–then it follows that a commitment to progressive thought and engagement proves integral to the absorption of geology in Shelley’s poem.

Nicole: What I really fell for in “Beachy Head” was the long stretch of meandering we did through what felt like a mix of memory and storytelling. It’s as though we are briefly on the ground at this place, then suddenly no longer conforming to space and time. I find that it’s deceptive at first. Can you talk about how you find the form of this poem lends itself to the underlying story?

Arden: “Beachy Head” is such a rich poem, generically as well as geologically. Although it’s clearly working in the Romantic tradition in its description of sublime natural landscapes, it also looks back to an older genre — the loco-descriptive poem — which characterized eighteenth-century works like James Thomson’s The Seasons (1726-1730). In the loco-descriptive poem, the speaker’s point of view moves fluidly between spaces through the act of looking, and the poem describes the different landscapes in view; importantly (and in contrast with most Romantic poetry), the energy carrying the poem isn’t so much the developing emotional charge, but rather the speaker’s changing observational position within a landscape. This active eye prompting topographical transitions is much of what we get in Smith’s 1807 poem, especially in lines like these: “let us turn / To where a more attractive study courts / The wanderer of the hills” (447-49). Here, Smith signals how her speaker’s eye carries “us” between geographical sites and their relation to her memories.

But, as you suggest, Nicole, Smith’s work is compelling because the landscapes in question prompt temporary flights away from the locations that she describes — including Beachy Head itself — as the speaker contemplates their relation to her emotional state. These jumps away from the landscape into recollected emotion is what feels most Romantic about the poem. For example, Smith’s denunciation of happiness is one of the work’s most poignant moments: “Ah! who is happy? Happiness! a word / That like false fire, from marsh effluvia born” (258-59). To me, this is an intriguing moment for the poem’s physical environment, since the simile associates happiness with a paranormal feature (a will-o’-the-wisp), in contrast to the many concrete landscapes of the poem — Beachy Head itself, the stone quarry, the cottages, the cave in the rock, and so on. But the ignis fatuus also helps to reveal the poem’s ongoing mechanism for the speaker’s nostalgic leaps: here and elsewhere, the ground gives direct rise to the emotions that the speaker experiences. (As a side note, “false fire, from marsh effluvia born” also invokes the miasmatic theory of disease popular during the period, which maintained that toxic gases would arise from the ground and spread contagion – a rather chilling way of describing “happiness”).

The historical and biographical contexts of “Beachy Head” are also quite interesting with respect to the poem’s treatment of time and space, especially in a scientific context. While writing was a source of necessary income for Smith (she was the only earner for her ten children), she took pleasure and relief in scientific practices like botany, and it seems to me that her somewhat loco-descriptive survey of the landscape of Beachy Head alludes to her personal practices of dispassionate scientific observation. An early reviewer of the posthumous poem remarked that

“It appears also as if the wounded feelings of Charlotte Smith had found relief and consolation […] in the accurate observation not only of the beautiful effect produced by the endless diversity of natural objects[,] but also in a careful study of their scientific arrangement, and their more minute variations.” (Monthly Review, 1807)

In keeping with what this reviewer notices, one of the poem’s main projects seems to be to classify different types of rock — the “chalk […] sepulchre” of the cliffs (723), the “stupendous summit” of Beachy Head itself (1), the “castellated mansion” (514), the “stone quarries” (471), and even the sedimented sea-shells, fossils, and “enormous bones” beneath the sea (422). But the poem also moves beyond classification by relating natural forms to poetic lyricism: for example, Smith describes “one ancient tree, whose wreathed roots / Form’d a rude couch,” where “love-songs and scatter’d rhymes” were “sometimes found” (581-84). At the poem’s conclusion, the rock of Beachy Head itself inspires verse, as “these mournful lines, memorials of his sufferings” are “Chisel’d within” (738-39); indeed, Smith’s own lines appear to have emerged from the physical rock. Moreover, supporting its thematic transitions between spaces and even outside of time, “Beachy Head” isn’t confined to a single verse form — the two sets of inset songs (in variable quintains and sestets) break up the sedimented quality we get with the long passages of blank verse. So the meandering quality that you notice between the poem’s specific geographies and abstract memories also applies to the fluctuating relationship between the verse forms, between the various locations and historical moments the poem describes, and, perhaps most importantly, between the relationship of scientific and poetic practices, which Smith ultimately tries to reconcile.

Jacob: Arden, I was particularly struck by the wonderful resonance between your suggestion that we read Charlotte Smith’s “Beachy Head” and Nicole’s decision that we look at Blane de St. Croix’s Broken Landscape III (Fig. 1), since both works utilize geology as a means to think through the concept of national boundaries. In what ways might the ideas you find in Broken Landscape III intersect Smith’s poem? Just as well, how might de St. Croix’s strategies as a visual artist diverge from those of Smith as a poet?

Arden: I’m so glad that you drew my attention to the political similarities between Charlotte Smith and Blane de St. Croix’s works. Both artworks are connected in their different ways to the question of politically-charged national borders. Smith’s perspective can certainly cast new light on de St. Croix’s contemporary art, and I see at least two ways in which the pieces can work together in productive dialogue. First, their portrayals of their respective borders share certain formal similarities, in spite of the very different natures of the artworks. Second, the works diverge in the mechanisms by which they represent the borders as liminal spaces: while de St. Croix is invested in showing how the deep strata of the Mexico-US border’s geological formation acts as a barrier between the nations, Smith finds that the France-England border’s geology reveals similarity underlying the nations’ apparently radical differences.

Both artists engage with the idea of sedimentation as a formal tool for political commentary. In “Beachy Head,” Smith regularly draws the reader’s attention to Beachy Head’s distinctive white cliffs, the tallest in Britain, whose layers of chalk point to a long-standing geological history of increasing division from the opposite coast by means of marine erosion over millennia. For Smith, the continual geological breakdown between the two nations, through this process of erosion, is a provocative metaphor for their political relationship. In its allusions to the Norman Conquest, the battle of Beachy Head of 1690 (which the English lost), and the tensions between the nations during the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, the “scroll voluminous” of “Beachy Head” offers a versified representation of this erosion (122). Presented in chronological order, each incident of conflict with France gives way to the next until the reader reaches sea-level and England’s triumph: “But let not modern Gallia form from hence / Presumptuous hopes” against England, the “Imperial mistress of the obedient sea” (146-47, 154). In the political ramifications of its eroding structure, “Beachy Head” has much in common with Broken Landscape III, which is also interested in the sedimentation of a politically-charged international border. For de St. Croix, however, the formalism of sediment is not figured through erosion, but rather through accretion. Discourses about the border have, over time, accumulated in layers, just as layers of rock have accreted in the border’s geological history. De St. Croix’s representation of the border as a human-scale sedimented wall explores how its underlying discourses have built up to create an insurmountable barrier in the present (unlike the real border, de St. Croix’s installation actually prevents the viewer’s ability to walk across it).

At the same time, though, the two works differ considerably in the function of their sedimentation. As Lily Gurton-Wachter argues, Smith resists the idea that France and England were “natural enemies” (a term used pejoratively to describe their strained relationship at the turn of the nineteenth century), and instead finds a common ground for them in their shared geological past. The poet contemplates whether the bottom of the sea, cast up in cliff form at Beachy Head, serves as the area of continuity between the nations: “Does Nature then / Mimic, in wanton mood, fantastic shapes / Of bivalves, and inwreathed volutes, that cling / To the dark sea-rock of the wat’ry world?” (383-86). While at one point Smith calls Romantic geology “but conjecture” (398), the general implication of the poem is that geology can help to locate a literal, deep-seated common ground between the opposed nations. De St. Croix, on the other hand, finds only political difference in the geology underlying the border. The human imposition of international boundaries on the surface of the earth is so metaphysically weighty that it actually carries downwards physically into its subterranean strata, in spite of the fact that each nation’s side is effectively the same in material and appearance.

Arden: Nicole, I’m interested in your thoughts on the materiality of landscape as a source for art. In Robert Smithson’s film about “Spiral Jetty,” the artist says that “the earth’s history seems at times like a story recorded in a book, each page of which is torn into small pieces. Many of the pages and some of the pieces of each page are missing.” How do you see geologically-inspired works of art — especially an “entropic” project like Smithson’s, or Blane de St Croix’s meticulous topography — engaging with the materiality of literary texts? And, how does your study of Romanticism help you to understand this material relationship?

Nicole: It’s especially remarkable when you come upon stacked strata in the field and see rocks lined up like books on a shelf. This metaphor instantaneously becomes ingrained within you as you run your finger down the stack, looking for the book (rock) you want to pull out. In the history of the earth, pages, sometimes whole volumes go missing. We suffer those convulsions and catastrophes, and the earth rebuilds itself from the pieces. Spiral Jetty is made from rocks, water, mud, evaporites, and time (Fig. 2).

But not just that, it is a place. Spiral Jetty is difficult to reach, sometimes not able to be seen due to changes in the level of the Great Salt Lake. In reading romantic-period texts, I’m reminded of the overwhelming sense of the sublime that artists felt for certain places. Certain topographies, either remote or only able to be accessed by memory (as so wonderfully illustrated in “Beachy Head”) hold a history that engages and sometimes mystifies. So, too, does the Broken Landscape series by de St. Croix as it not only shows the surface, or present tense, but it digs into the depths of what came before our tense border anxieties. Broken Landscape III looks directly at ontological constructs upon the landscape that never existed before human-made activity, but doesn’t negate the rock record.

What I find fascinating is that this rock record is always around us, ever complex yet at our disposal to read. There is some comfort in the idea that we can make sense of the word, quite literally, by translating it like an ancient tome. I think that through Romanticism, I’m actually able to understand more about the emotional weight I give to rocks themselves. By reading through the Scottish Enlightenment and the geological revolution, I understood that what I was going through artistically was my own new science: a way of naming and identifying my emotions without feeling them – calling them the Other.

Jacob: This year, I’ve become increasingly influenced by Rebecca Beddell’s The Anatomy of Nature: Geology and American Landscape Painting, 1825-1865 in terms of the way in which, as Beddell explains, the division of labor between artists and scientists is essentially a discursive construction. Namely, here, I’m interested in how reading Bedell’s art-historical analysis might relate to, or gave you a space to imagine, your own work, perhaps in a different way than you had prior. In this regard, I’m drawn especially to the preface to her book, where Bedell suggests that in the nineteenth-century: “American landscape painters and geologists then stood on common ground. We now tend to consign art and science to different epistemologies, regarding them as distinctive pursuits, with completely different methodologies, directed towards completely different ends” while in the nineteenth-century art and science proved an interconnected spectrum of pursuits “in both popular perception and practice” (xi). What I’m wondering is how you consider about your own work within this trajectory. I’m thinking mainly of your 2011 Secondary Sediment series of prints that I think so powerfully evokes the relation between personal memory and geological space, and especially the play of text and image in “IX” (Fig. 3).

Nicole: Jacob, this is such a great question, because I specifically thought about this, too, when I was reading Beddell’s introduction. It seems a social construct based on educational or vocational pursuits has rendered art and science separate pursuits in our recent history, but the idea of a more common acquisition of knowledge and shared respect for these fields was in vogue during the age of Manifest Destiny. A different resurgence in this kind of thinking is afoot, with places like Science Gallery (https://dublin.sciencegallery.com/), the resurrection of LACMA Art + Technology Lab (http://lacma.org/Lab), and the CERN Artist’s Residency (http://arts.web.cern.ch/collide), to name only a few art and science collaborations.

To answer your question, my work does straddle both realms. It’s a mix of personal memoir related to the land it was experienced in. I find that the economic aspects of landscape cannot be separated from their role as passive backdrop to this “American dream” sedative. To deal with one part of the land or the space I live in requires me to seriously investigate all parts – it’s an element of knowing the land that I think a poem like “Beachy Head” deals with in a wonderful way.

The idea that we should mine the earth for its riches, or fight wars for those resources, the same principles that as a youth I could feel patriotic about, are now the ideas that I question in my work. What is worth exploiting (property, resources, and lives) and at what cost for the betterment of humankind? Who can really own land? In “A Place on the Glacial Till,” Thomas Fairchild Sherman writes a personal, historical, and geological history. A story of the animals and plants of his native Oberlin, Ohio, he writes of a place that is clearly familiar and dear to him when he says that: “Our homes are but tents on the landscape of time, and we but visitors to a world whose age exceeds our own 100 million times. We own only what the spirit creates.”

At what cost does the land stop becoming land? I think Solnit shares a fine example of this in her essay (see “Elements of a New Landscape,” 57). The work “El Cerrito Solo” by Lewis deSoto was initiated by a friend’s remark that it was “too bad the mountain wasn’t there anymore.” Essentially, a small hill had been sourced for it’s material until it was no longer there – a story that’s full of what I think of as the ripping out of a page from one of the volumes in the rock record of the earth. Almost painfully, the artist says, “you could be in the landscape while driving on the freeway.” This reminds me of living in South Dakota and driving on pink-hued roads, colored this way because of the quarrying of local Sioux quartzite, the words of this story echoing in my thoughts. How many “little mountains” disappeared from the landscape to make these roads? At the intersection of art and geology, I read of a similar story that took place in Belize of the unfortunate destruction of a 2,000+ year-old Mayan temple, locally named Noh Mul, or Big Hill. A local contractor was quarrying the site for its limestone to create roadfill, but now embedded archaeological artifacts are totally lost and broken cultural relics have become part of the landscape. Ultimately, the “otherness” of Nature is no longer a separate entity conceptually at bay but is a real, interactive part of our lives. I believe art can help us transform the way we think about landscape and its effect on us.

(Link: http://hyperallergic.com/71065/ancient-mayan-temple-destroyed-in-belize/)

(Link: http://edition.channel5belize.com/archives/85391)

I think the time is right to invest in people. One of the biggest problems that I see with contemporary Western culture (as this is what I can speak to), is a lack of focus on local histories and real science, and an art world that seems fixated on the cult of celebrity, or too quickly moves on from one fad to another. I think the reason I became a printmaker was that somewhere at the core of my being, I enjoy the slow work and old-fashioned ethos of making something from an antiquated technology. It’s possible that I set myself up to be interested in history specifically because of that, but a lot of the work I drift toward or care about is art about the sciences and questioning the role of the author, or the authoritative voice. By this I mean searching for authentic stories of people so that they not be forgotten by history due to their gender, race, or sexuality. I look for things to have meaning and depth beyond their surface. Rocks and big outcrops, with their stony gazes, seem to have a lifetime of stories to tell, even if their faces are unyielding. I have to agree with Shelley on this point, where he ascribes a voice to Mont Blanc–in the lines to which Arden first drew our attention. What I read in this passage is the work of the artist and the geologist. To make the voice of the mountain known, through study and familiarity, through knowledge and wisdom, and to transmit that feeling through the power of metaphor, and of unity with the landscape. Who can say which job belongs to whom?

Works Consulted:

Poetry

Felicia Hemans, “The Rock of Cader Idris” (1822)

Percy Shelley, “Mont Blanc” (1817)

Charlotte Smith, “Beachy Head” (1807)

Art

Blane de St Croix, “Broken Landscape III” (2013)

Robert Smithson, “Spiral Jetty” (1970)

Criticism

Bedell, Rebecca. The Anatomy of Nature: Geology and American Landscape Painting, 1825-1875. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

Gurton-Wachter, Lily. “’An Enemy, I suppose, that Nature has made’: Charlotte Smith and the natural enemy.” European Romantic Review 20, 2 (2009): 197-205.

Heringman, Noah. Romantic Rocks, Aesthetic Geology. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004.

Solnit, Rebecca. “Elements of a New Landscape.” As Eve Said to the Serpent: On Landscape, Gender, and Art. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2001.

"I have a new leaf to turn over:" A Romanticist's Resolutions for 2014

I think we can all agree that Keats’s Endymion (1818) was a critical and commercial failure. As Renee discusses in her post, Tory reviewers lambasted the poem because of Keats’s affiliation with outspoken radical Leigh Hunt. Although the poem’s most notorious critic, John Gibson Lockhart, notes its metrical deviations from the traditional heroic couplet form, he spends more time attacking Keats personally: “He is only a boy of pretty abilities, which he has done every thing in his power to spoil.” It’s no wonder, then, that Keats’s letters written in the months that followed show a recurring preoccupation with self-improvement, or “turning over a new leaf.” In a short letter to Richard Woodhouse (friend and editor) dated December 18, 1818, he writes “Look here, Woodhouse – I have a new leaf to turn over: I must work; I must read; I must write.” He’d repeat the phrase again that April in a letter to his sister, complaining that he had “written nothing and almost read nothing – but I must turn over a new leaf.”

Due to my unfortunate tendency to self-identify with whomever I’m reading (“OMG, Keats, I know EXACTLY what it’s like to have your work rejected and then mooch off your friends because you have no money. WE ARE THE SAME PERSON.”), Keats’s desire to “turn over a new leaf” resonates as I prepare for a new semester of graduate school in the new year. While our situations are slightly different – constructive criticism of a seminar paper not quite as devastating as the complete and utter failure of a published book – his mantra for self-improvement sounds eerily like that of a graduate student: “I must work; I must read; I must write.” In the spirit of turning over a new leaf, and hopefully transforming that Endymion-esque seminar paper into a Lamia, I present to you my academic resolutions for 2014. I should note that many of these will be obvious to the more seasoned scholars among you, but for all of you newer grads out there, I hope you’ll find my mistakes instructive.

Resolution #1: I will develop arguments from texts instead of making texts conform to my arguments.

This one seems easy in theory, but it’s something I’ve been struggling with throughout the semester. I’ll read one text – Endymion, let’s say – and then a bunch of criticism, and its reviews, letters, etc. Then, I’ll develop an idea about how Keats’s later poems revisit the same genre and politics as Endymion, but ultimately rewrite them. Except, I’ll form this connection even before I’ve read the later poems, just because it sounds so smart and will make such a good paper. Then, I’ll set about writing the paper and finally get around to reading Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and other poems (1820), and only then will I realize that the texts interact in completely different ways than I had originally thought. Of course, there’s not enough time to completely rewrite my paper, so I stick with the argument, praying that the reader doesn’t realize I made this crucial error.

So, simply put, I resolve to stop doing this faulty method of research. I’m going to let myself be confused by texts, and stop trying to develop beautiful, complex arguments before I’ve had time to fully read and think about them. If a brilliant idea pops into my head before I’ve done this, I’ll write it down, set it aside, and consider it later. As a wise professor once told me, “Always start with close reading. If you leave it till the end, it will always most certainly change your argument.”

Resolution #2: I will accept that I am, first and foremost, a student.

A wise man (Michael Gamer) once told a group of English majors, “graduate students are full of themselves.” I hate to say it, but I’m living proof of this. I started graduate school last August under the impression that I was a Romanticist. In my undergrad days I was merely an “aspiring Romanticist,” but starting a Ph.D. program gave me the right to crown myself with the full title. Once I was accepted, I thought that I had made the transition from student to scholar, and deceived myself into believing that I knew more about my field than I actually do. Thankfully, the enormous ego that Michael prophesied was soon deflated when I realized a few weeks into class that, in fact, I know very, very little about the period in which I claim to specialize. Of course, this realization was accompanied was a decreased sense of self-worth, doubt about whether I was in the right line of work, and a frantic conversation with my advisor in which I dramatically exclaimed, “I KNOW NOTHING!” “That’s ok,” he assured me, “you’re a student, and you’re not supposed to. Frankly, you’d be surprised how many people in the field don’t know much either.” So, for 2014, I resolve to remind myself that I’m not a scholar yet; I’m a student. I will accept the limits of my knowledge while doing my best to expand them.

Resolution #3: I will overcome writing anxiety.

This problem plagues many of us, and it’s one of my biggest areas for improvement in the new year. Sometimes, the sheer size of what I need to write, the nearness of the deadline, and difficulty of the subject matter create a Kafka-esque paralysis in which no writing is accomplished. I can tell I’m experiencing this when I go to extra lengths to avoid starting a paper, whether it’s extra research, extensive outlining, or a meticulously organized Spotify playlist entitled “Writing.” As many of us know, talking about writing and thinking about writing is not actually writing. The only way to overcome this problem is simply to write more. At the advice of many of my peers, I plan to write everyday, especially while I conduct research. There were simply too many times this year when I was tempted to end my seminar papers in the way that Milton ended “The Passion” (1620): “This Subject the Author finding to be above the years he had when he wrote it, and nothing satisfied with what was begun, left it unfinished.” I’m pretty sure only Milton could pull off that one.

Resolution #3.5: I will write my blog posts on time.

This probably should’ve been number one. Thank you, Jake and fellow NASSR grads, for your patience.

Happy 2014!

Interview: Dr. Michael Chwe

Emma Woodhouse reflects upon notions of truth and strategy, stating, “Seldom, very seldom does complete truth belong to any human disclosure; seldom can it happen that something is not a little disguised, or a little mistaken.” Famous for being the only one of Jane Austen’s heroines who “no one but [herself] will much like,” Emma reveals a dangerous fact that we all know instinctively: the complete truth rarely exists without some sort of agenda.

But, sometimes, an interpretation of Austen’s agenda is inspired by complete coincidence. Dr. Michael Chwe explains that finding the children’s book Flossie and the Fox at a garage sale was the beginning of his project, titled Jane Austen, Game Theorist. Much has been said about our Austen in the past several years—we’ve asked questions about her sexuality, questions regarding her censored letters, and questions about her publication history, but we’ve never considered her a game theorist until now.

Chwe’s book Jane Austen, Game Theorist supports Emma’s assertion, and argues that “Jane Austen systematically explored the core ideas of game theory in her six novels, roughly two hundred years ago” (1). Chwe looks at how Austen’s characters negotiate the main principles of game theory: choice (a character does something because they want to do that action), strategic thinking (a character does something based upon how they think others will perceive and respond to it), and preferences (a character does something because they prefer it over another option). The result is an interesting, interdisciplinary analysis of Jane Austen and her work.

INTERVIEWER

You mention in the preface of your book that this project started when you found Flossie and the Fox at a garage sale for your children. You used this experience and paired it with all the years you spent teaching and reading folktales and Austen to create Jane Austen, Game Theorist. Can you tell us more about how you came up with your idea and how it changed over time?

CHWE

The original title of the book was called Folk Game Theory, which revolved around the idea of people who use game theory who are not traditional game theorists. The examples were folk tales, and I actually had a whole chapter on Rogers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma, the musical. But, most of it was Austen. Seventy, eighty percent was Austen. So, one of the [manuscript] reviewers said, “You should just say that this is about Austen.” It was a good choice. The original idea was to say that this book is many instances of people who are developing game theory, not necessarily in a theoretical way, but through narratives […] In my teaching, I use examples from movies and other things to show students, so I’m always on the lookout for more examples […] I got interested in Austen after I saw the movie Clueless. Then, I started watching Austen movies. And then, I started reading her books. That’s how the whole Austen thing came about.

INTERVIEWER

That’s incredible. So, Clueless was your gateway into Austen.

CHWE

It was indeed. Yeah, I never read Austen in college or in high school […] In college, I never took a literature class, so I didn’t read Austen until I was like forty. I’m glad because if I had read Austen in my twenties, I wouldn’t have understood a lot of it, to be honest.

INTERVIEWER

Was Emma the first of Austen’s novels that you read?

CHWE

I originally thought the book [Jane Austen, Game Theorist] would talk about Emma as just one case because it is so clear that Emma is about manipulation and meddling […] I thought I’d focus this book on Emma, but then I wanted to read the other books and see what I could say about them […] I think that if Austen had written twenty or thirty books, I wouldn’t have been able to read all of her books, but because she only had six, I thought I’d just go ahead and do it.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a favorite Austen novel?

CHWE

No, I really like them all. Pride and Prejudice is a little shallow to me in the sense that most of her characters are fully formed at the start. To me, Mansfield Park is better because it’s about the development of a human being. People change more. Persuasion, I also like a lot. So, those are my favorites, but, of course, I like them all.

INTERVIEWER

In terms of your book, what was the publication process like?

CHWE

I was lucky in that I had already published a book with Princeton […] back in 2001. So when the time came around to think about writing a book again, I sent it to Princeton. I also sent it to Oxford University Press. Neither place had problems with the idea being a little bit non-standard, but it was hard to find reviewers on the literature side […] Everyone talks about how important it is to do interdisciplinary work, but it is harder in a sense because people have a harder time judging it.

INTERVIEWER

What do you make of EverJane, the online role-playing game based upon Jane Austen novels? Have you played it? What might it say in terms of your argument?

CHWE

I haven’t played it, but I think that it’s a great idea and that it has potential. I saw the Kickstarter page. I think, potentially, it is a great way for people to get into Austen and I think Austen’s world view is very much about the decisions you make to get ahead and how important a single decision can be. I think that Austen’s literary worlds are worlds where […] you think about yourself in terms of decisions. Other people’s worlds might think in terms of visuals or characters or history, but when you think about Austen’s worlds, it’s about […] what would you do? What would you think about? What connections would you make?

INTERVIEWER

What I’m wondering right now is do you see EverJane as a physical representation of your argument? Or, I guess, a virtual representation?

CHWE

I haven’t worked with the game, but maybe. I’m not sure how they structured the game […] I think because Austen emphasizes decision making so much, maybe her novels are most suited for this kind of thing…For example, if I made a game out of Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse, I’m not sure what that game would look like. So, some novels don’t necessarily lend themselves, but I think Austen’s do.

INTERVIEWER

I understand your argument as an interpretation of Austen, herself, as a game theorist, as well as the notion that she portrays her female characters as game theorists—that is, Austen extends her own strategic thinking to her characters, which is demonstrated through their culminated marriages. How might readers navigate your argument if we don’t view Austen’s novels as strictly heteronormative? How might Austen’s game theory change?

CHWE

I don’t see Austen’s novels as all that heteronormative. There’s a whole thing with Henry Tilney […] [and] gender roles. There’s the discussion with Catherine Morland and Henry Tilney, where he says that women have so much talent that they don’t need to use more than half…I think its representative of the questions: Are women better at strategic thinking than men? What are the social determinants of that?

When Henry Tilney buys the muslin for his sister, that’s like him being in drag or being gay or bisexual…But back to marriage—I’d say that you can think of [game theory] more in terms of social advancement. I think that Austen is trying to be general and is saying: this is how you can understand human behavior […] Marriage is just one of those possible objectives, so [game theory] doesn’t hinge on the idea that marriage is the final goal. For example, in Northanger Abbey, if you think of Henry Tilney as not as stereotypically masculine as other characters, maybe he could have been in touch with his feminine side. He’s one of the better strategic actors in the novels. He doesn’t make huge mistakes like Mr. Darcy does. I think Henry Tilney, more than any other male character, explicitly says things about strategic thinking. He talks to Catherine Morland and says, “When you think about other people’s motivations, you think about them in terms of what you yourself would do, as opposed to what a person of their age or their status would do.” That’s a very clear explication of the problem of strategic thinking. We always tend to think of people in terms of ourselves. We’re not necessarily good at putting ourselves in the mindset of others. Henry Tilney says that. He has a definite feminine side. He’s not as stereotypically masculine as some of the other male heroes […] I don’t think [Austen] takes heterosexuality as necessarily as a given.

INTERVIEWER

So, the game theory wouldn’t necessarily change at all, even if marriage wasn’t the end goal.

CHWE

No, not at all. Austen thinks getting married is important to their world, but she doesn’t necessarily see [marriage] as a sacred life goal. Her interest is more about the process. She’s not interested in what happens to people once they’re married […] She’s interested in how people get to that goal.

INTERVIEWER

You argue that Austen, herself, was a game theorist. How might considering Austen’s own strategic thinking complicate traditional ways of viewing her work as domestic narratives?

CHWE

I’ve never myself been concerned with the critique that just because she talks about five or six people […] that somehow her work is not significant. All game theorists and a lot of social scientists realize that you can explore interactions amongst a handful of people. Those can have applications to a very large group of events. When I teach game theory, the most interesting parables are those between two people and then you generalize them. A parable or story about people deciding whether to cooperate or fight each other over painting a fence […] can be a parable for international relations or war. The very fact that Austen doesn’t talk about historical things or a huge world event has nothing to do with whether her ideas are applicable or generalizable. Any social scientist would say that. There’s no reason to think that just because it’s a domestic narrative that the insights there may not apply to lots of other things. I think that we shouldn’t think necessarily of a narrative or novel in terms of its subject matter but in terms of its vision for how people interact with each other. Those insights can apply to many different cases.

It’s like slave folktales. Slave folk tales are tales about animals, but they’re not about animal behavior. They’re used to talk about uprisings or strategic techniques that slaves can use against their masters […] They tell narratives about rabbits and foxes—it’s obvious that these slave folk tales are about, in terms of their subject matter, animals. But what’s relevant about these specific strategies is that they express techniques that these animals use against each other.

INTERVIEWER

Interesting! How does game theory apply to scholars in Romanticism? How might game theory be used to enhance literary criticism, appreciation, or cultural study?

CHWE

I think that the obvious thing is to use game theory to illustrate aspects of novels. Game theory might come from a situation like a prisoner’s dilemma—these are situations where people can gain if they all cooperate, but no individual person wants to cooperate–so [scholars in romanticism] might say, “In this novel, I’ve found an example of a prisoner’s dilemma and this is how they solved it.” You could do that. With Austen, I did something a little bit different, which is to say that we’re not using game theory to understand her work, but rather, we’re trying to understand her as a game theorist herself. This won’t be the case for every single author. Some authors may be more interested in emotions or social context or irrationality or self-perception or delusion […] If you’re aware of how people in the social sciences try to make explanations for things, you can maybe use them to understand how certain authors seem to be expressing theories of human behavior. It might be another way of analyzing their work.

For example, since I was working with game theory, I was really monomaniacally thinking in terms of choices and in terms of purposeful action […] so I was really sensitive to those issues. […] People who are interested in psychology or how we constitute the self can also take that to literature. Some people have taken that to Austen.

It can’t hurt to be aware of certain [social science] ideas and where they come from […] If you’re sensitive to these things, then you might find another avenue for reading other people’s work and understanding their objectives […] In Austen’s time, there wasn’t anything called social science or a systematic discipline for understanding human behavior. If you were interested in human behavior and wanted to analyze it, probably, you ended up going to the novel. That’s what you did back then. If we think of understanding human behavior, we shouldn’t think of this as a specialized thing—it’s something that we all do. It’s not surprising that if you’re a novelist or a writer and thus you have to think about human behavior, part of you develops some sort of theory about it.

Romantic Geologies and Post-Organic Forms

I’d like to begin by thanking the NGSC for welcoming me to this year’s blogging roster. It is a pleasure and privilege to write alongside these intriguing and diverse graduate scholars, and I’m looking forward to reading the material our collective will produce this year.

The blog posts we’ve seen already have been so compelling, both intellectually and personally, that I would like to continue the conversation by engaging with the fundamental questions previous posts have posed. “Fundamental” seems to be a key word for us, as we think about how the foundations of our scholarly temperaments act as cornerstones for our intellectual flights. As Nicole and Deven’s posts illustrate, we can describe this layered relation of the personal to the scholarly by drawing on material metaphors of sedimentation, accretion, and metamorphosis.

Deven and Nicole’s descriptions of their scholarly uses of archaeology and geology—as accretive fields that can inform their work with the material aspects of literary texts—come at a fortuitous time, for me at least. I have been thinking about how aspects of literary form can be captured through scientific metaphors, and their posts have sparked my interest in thinking about how geology and Romantic poetic form intersect.

Geology is a fascinating area within the Romantic sciences, partly due to the period’s uncertainty about whether “rocks and stones and trees” formed an organic continuum. This problem of unclear organicity dated back at least to Buffon’s 1749 proposal that mountains were formed when “all the shell-fish were raised from the bottom of the sea, and transported over the earth.” During the height of British Romanticism, the problem of distinguishing between organic and inorganic forms was compounded by the discoveries of giant fossils of extinct lizards between sedimented layers of rock. In 1809, the natural scientist Georges Cuvier, who had already examined the fossil of a giant sloth and coined the term mastodon, classified these reptilian fossils as the Mosasaurus and the Ptero-Dactyle, leading the charge for the study of dinosaurs, which was to reach a high point in the discovery of the iguanodon in the 1820s. As a geologist as well as an early paleontologist, Cuvier was faced with the challenge of defining sedimented organic forms as both crucial to, and distinguished from, non-living terrestrial matter.

This instability of Romantic geology shook the foundations of the period’s poetry. Though we might usually think of huge and ancient organic forms first emerging “to rise and on the surface die” in Tennyson’s 1830 poem “The Kraken” (l. 15), Romantic literature abounds with buried dinosaurs and geological eruptions. Keats’s Endymion witnesses skeletons “Of beast, behemoth, and leviathan [and] Of nameless monster” on the ocean floor (III, 134-36), while in Cain, Byron challenges the usual Biblical chronology by referring to the “Mighty Pre-Adamites who walk’d the earth / Of which ours is the wreck” (II.ii, 359-60). Likewise, in Prometheus Unbound, Shelley describes at length the “monstrous works and uncouth skeletons” and “anatomies of unknown winged things” that lie buried in the deep (IV. 299, 303). Moreover, geology could help describe the poetic process: we see this best in Byron’s celebrated metaphorical account of his own creative tendencies, with his passions building up internally and finally erupting volcanically into verse. (Meanwhile, in Don Juan, he jokingly writes, “I hate to hunt down a tired metaphor: / So let the often used volcano go. / Poor thing! How frequently, by me and others, / It hath been stirred up till its smoke quite smothers” [XIII.36]). At the same time, though he doesn’t acknowledge it, Romantic geology poses a problem for Coleridge’s definition of literary organic form, which considers the growth of the text from its inception to its adult shape—not its later stages of death, decay, and post-organic potential re-use.

Today, Romantic geology, with its imagery of defunct and sedimented layers of organicity, has profound implications for how we think about poetic form—particularly the forms of Romantic poetry. Geology is a key metaphor for many Romantic critics: David Simpson, for instance, writes that “a great deal of Wordsworth’s poetry is best approached as if it were a core sample of an especially contorted geological substrate. One works with a rough prediction of how the layers ought to relate one to another, but there are continual local deviations and surprises.” Moreover, in recent New Formalist arguments, the sedimentation of dead organic matter can be a crucial motif for thinking abstractly about the life-cycle of a literary form or genre. Recently, I read a very compelling essay, Group Phi’s “Doing Genre” (in New Formalisms and Literary Theory, eds. Theile and Tredennick, 2013), which takes geology, plasticity, and recycling as its governing metaphors. In this text, Group Phi proposes that “genre” is a “sedimented and metamorphic historical category that is received by readers,” and that “form” is the “the reader’s activity of adopting/adapting that category for further use”—more simply, that a genre is like a sedimentary rock, with accretions of its use built up over time, while form is like the wind, shaping the rock and depositing new layers of use upon it. Further developing this intriguing metaphor of geological sedimentation, Group Phi then discusses at length how genres can be “recycled” and “repurposed”—to my mind, invoking a layer of crude oil, the result of decayed organic matter, that is buried within the sedimented structure, drawn out, made plastic, “refocused, repurposed” and reshaped, and then recycled for future use. This is no doubt a metaphor of literary form characteristic of our own time, reflecting our concerns about the ethics of geotechnical excavation, and particularly the problem of violently appropriating formerly organic structures, now metamorphosed into inorganic matter (oil). Group Phi’s invocation of recycling, mid-way through the essay, is perhaps one way of “greening” their potentially problematic metaphor of the generic sedimentation of post-organic (literary) forms.

But the Romantics themselves may have something to say about these contemporary geological forms, and here I’m thinking of Shelley in particular. In Alastor, or the Spirit of Solitude, Shelley writes about the hero’s journey as he pursues “Nature’s most secret steps” to where the “bitumen lakes / On black bare pointed islets ever beat / With sluggish surge” (85-86). What Shelley means by “bitumen lakes” has long posed a problem for critics, who have variously identified them with the Dead Sea, with the lake of fire in Paradise Lost, or with molten lava-flows in general; the most obvious precedent for Shelley’s 1815 use of the term is Southey’s reference to the “bitumen-lake” in Thalaba the Destroyer (1801). To me, the image of bitumen lakes in Alastor points within Romanticism to the era’s own problem of uncertain organicity (compounding the animal imagery of decayed dinosaurs, “bitumen” introduces a layer of vegetable matter in its etymological relationship to “pitch”). Yet for today’s readers, Alastor‘s bitumen lakes gain much in the translation: “bitumen” is the correct scientific term to describe the heavy crude oil now being excavated—in part, through hydrofracking—from the vast tar/oil sands of Alberta. Anticipating one of the great environmental controversies of our time, Shelley’s prescient use of the geological term can perhaps cast light on the deep Romantic substrates of current forms of representation of the tar/oil sands project.

In short, building on Group Phi’s model, we might look more closely at how the geological realities that underlie our contemporary metaphors of form and representation are built upon a deeper layer of Romantic uses. The mixed organicism of geological sediment has rich potential for talking about poetic language. Recalling Shelley’s account of continually dying metaphors in A Defence of Poetry, Ralph Waldo Emerson writes that “language is fossil poetry”; we too might look to the strata of literature’s organic forms in our own search for deeper meanings within Romanticism.

Memoirs and Confessions of a Second-Year Ph.D. Student

Here are the facts as I know them: 1. There are never enough hours in a day; 2. I have students who still think I don’t know that changing their font from Times to Courier adds at least a page to their essays; 3. The long 19th century is such a joy to study.

I didn’t always know these facts. When I was an undergraduate English major, using Courier in every paper I wrote about books that I only partially read, I was aimless. I took classes in order to get my degree, I earned A’s, and I didn’t minor in anything. You could say that I wasn’t the most pragmatic person on the planet. At the time, I wasn’t fully focused on school or my future; my older brother had left for Israel instead of attending law school as he had originally planned, and I struggled, trying to understand his decision. Later, as I pondered what I might do after my B.A., I was torn between graduate school and law school. A Romanticism seminar in the fall of my senior year tipped the scales.

One of the first books that we read was Frankenstein, the first assigned book of my undergraduate career that I read cover to cover. What sold me on Mary Shelley’s work wasn’t the fact that she wrote in response to a ghost story competition—instead, it was an anecdote shared by my professor. He told us how he had inscribed the creature’s words: “I will be with you on your wedding night” in a card at his friend’s wedding. How clever, I thought. I, too, wanted to be that witty, literary friend at weddings, but I realized that I should not and could not quote a book that I had not read. It was the first time that I fell in love with a canonical work.

We read a lot of other interesting works in class, and– in case you’re wondering–I did actually read them in their entirety. However, it was the last assigned work of the semester that changed my life. But Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice didn’t grab my attention right away. So, to make it more animated, I began reading it aloud to my cats with different voices. Soon, I was invested in the characters. And then I brought my interpretation of the novel to class: I said there was an erotic attachment between Darcy and Bingley. My classmates reacted with violent disagreement. They took it personally—that is, they were uncomfortable with any reading of a famously heteronormative text that involved queer desire. In all honesty, their disagreement delighted me. It motivated me. It led me to attend office hours and read literary theory for the first time. I read Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Freud, Lauren Berlant, and Michael Warner. I wrote multiple drafts of my end-of-semester paper. And I realized that—just as my brother had done something unconventional that he loved—I loved writing about literature that I had actually read and thought about in unconventional ways; I needed to read for intellectual engagement, not just for pleasure or for finishing an assignment.

I didn’t know it then, but I had stumbled upon the subject I am most passionate about, the deconstruction of heterosexist interpretations of texts. You could say that Pride and Prejudice was my patient zero. As a MA student, I continued working with Austen; the next text that I plunged into was Persuasion, and then it was Emma. In my M.A. thesis, I argued that the heteronormative relationships depicted in Austen’s three novels are built and premised upon queer desire.

As a Ph.D. student who will enter into her final semester of coursework in January, I am actively compiling my exam lists and just as actively kicking myself for not actually reading for my first three years of college. The list of works that I’ve read, while growing, is woefully underdeveloped, and I see my exam lists as an opportunity to atone for my undergraduate sins. Even though I’ve been exposed to theory and a variety of tropes and texts, I remain interested in looking at texts—especially famous heteronormative love stories—and analyzing the ways in which desire functions. My dissertation will be a transatlantic study of desire and will further the ideas that I’ve been so passionate about since that seminar on Romanticism in my senior year of college.

PS. In case you’re curious–I have read Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner and therefore feel okay about using parts of Hogg’s title.

Towards a Tangible Romanticism; or, One Student’s Search for the “Real”

I have a confession to make: I’m not getting a Ph.D. in English because I’m interested in literature. An avid reader since childhood, books were something I enjoyed, but not necessarily found interesting enough to study. Sure, Pride and Prejudice was a great read, but I’d never thought it more than that. My early thinking went like this: “Fiction is entertaining, but it’s not real. What’s the value in studying something that isn’t real? If it isn’t real, what’s there to study?” This line of thought must abhor many of you, but I confess that I struggled (and still struggle) to convince myself that studying literature was a worthwhile, productive endeavor. It didn’t help that I went to a college where most students viewed education as a means to a well-paying job—a degree worthwhile for the job at Goldman it could score you. I was certainly influenced by this environment, and haven’t entirely discarded its thinking. I was, for better or worse, interested in the real, the tangible.

My quest to study something “real” (quite literally) led me to declare a major in Archeology, a field where I got to touch things and feel their realness. Literature was about ideas, archeology was about objects. A poem didn’t have the same tangible meaning for me that, say, a clay pot did. The pot was created for a purpose: to hold liquid, cook food, decorate a home. I liked that I could touch the artifacts I studied; they had real meanings behind them, not the “imaginary” meanings that people superimposed over novels and poems. You could find an object’s meaning within its material form—it had been shaped a certain way for a reason.

Yet a few months later, I found myself missing literature. I started to crave the “humanness” of books from which artifacts, although made by humans, felt detached. I started taking more English classes, mainly for fun, when an idea struck me: what if books could be read, not as abstractions upon which readers inserted meaning, but as objects? This watershed moment transformed the way I thought about literature, and led me to switch my major. I stumbled across a new kind of reading that I want to call an “archeological hermeneutics.”

How this works: I read a book as a material object, not only significant because it’s the product of a distinct cultural moment, but because it has a relationship to all other objects of the same type. In archeology, we think about a decorated Tlingit mask as it exists alongside hundreds of undecorated masks. The mask is both an independent object with a unique history, and a type working within a tradition of objects. Likewise, books are interesting, as opposed to entertaining, when I can read even the smallest moment in a text as related to the book’s position in its unique cultural moment, and as a product within a history of moments. So, when Keats writes Hyperion in unrhymed heroic verse, it’s significant on a local level—revising the verse form after the critical failure of Endymion—but also engages within a tradition of verse that hearkens to Chaucer, Spenser, Milton, Pope, and others. Books are both local and transhistorical artifacts.

In archeology, material constraints dictate what kind of objects people create. The indigenous peoples of the Great Basin make baskets out of yucca, a material which obviously constrains their shapes and colors. Applying this to my studies in Romanticism, the material conditions of a book’s creation, publication, and dissemination are important to my understanding of its content. As I’ve learned in my current course on Romantic Drama with Jeffrey Cox, the material conditions of Regency theatre culture—there were only 2 theatres in London allowed to perform spoken drama—led to the development of musical forms like melodrama, pantomime, and other forms of Jane Moody’s “illegitimate theatre.” And then there are the constraints of publication: Why does Equiano choose to publish by subscription, and why does he include a list of subscribers on the first page of his Narrative? Does it affect our reading of the narrative that follows? These are the questions, inspired by Romanticism’s material conditions, that I find worth discussing. To me, they are real, almost tangible.

Yes, there are benefits to reading books as closed systems. It’s useful to understand how a text functions within itself, how it teaches the reader to read. But often with this approach, the meaning I find within texts is one I’ve placed there myself. Nietzsche (and Paul Youngquist, from whom I first heard it paraphrased) explained it thus: “If someone hides something behind a bush, looks for it in the same place and then finds it there, his seeking and finding is nothing much to boast about.” In my burgeoning career as a Romantic scholar, I want to discover truths that emanate from texts without having to place them there myself.