This is a post about an issue near and dear to our hearts as bloggers and blog-readers: digital authorship, authority, and recognition. Kathleen Fitzpatrick, author of Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology, and the Future of the Academy, spent two days at Lehigh University. September 12th, she gave a presentation called “The Future of Authorship: Scholarly Writing in the Digital Age” and September 13th, she spoke informally with grad students and faculty. Here’s some food for thought based on her visit.

Fitzpatrick started out with the basics: what kinds of authorship do we as academics value, and why? We value work that is done on an individual basis, thus making it simpler to claim ownership and award credit for the work produced in a final, polished product: I wrote this journal article, did all the research and drafts myself, gave credit through proper citations, and went through the process of revision and peer review and, finally, publication. Lots of people are involved in this process, from the other authors cited in the article, to the editorial board and anonymous peer-reviewers. But we don’t see those names on the by-line.

And this is Fitzpatrick’s point. With so many people involved, we recognize that an article is not published by the author alone, even if we pretend this is the case in our C.V.s and tenure reviews and job applications. Fitzpatrick argues that reading and writing are social activities and are continuing to become even more social  through digital media forums like online journals, blogs, social media, twitter, etc. She claims that we need to rethink the ways that we share information through technology, how we reach and interact with an audience, how we control (if, indeed, we should) quality and authority, and how we give credit for all the labor that goes into commitment to an online community. We need to consider the process as much as the final product, if not more so, in order to benefit from the development of an idea through over time, which is what makes online work so exciting. One of the last points with which she ended her talk was the emphasis on the spread of knowledge for its own sake, in order to let it grow and expand into different forms and fields. Make it as accessible as you can. Certainly, none of us are in it for the money, after all.

through digital media forums like online journals, blogs, social media, twitter, etc. She claims that we need to rethink the ways that we share information through technology, how we reach and interact with an audience, how we control (if, indeed, we should) quality and authority, and how we give credit for all the labor that goes into commitment to an online community. We need to consider the process as much as the final product, if not more so, in order to benefit from the development of an idea through over time, which is what makes online work so exciting. One of the last points with which she ended her talk was the emphasis on the spread of knowledge for its own sake, in order to let it grow and expand into different forms and fields. Make it as accessible as you can. Certainly, none of us are in it for the money, after all.

I don’t consider myself to be hugely involved with all the newest technologies associated with digital information, and things like “open access” are still mysterious to me (and, I’ll admit, I’m still trying to figure out how to best use Twitter, both personally and professionally). Yet, I am involved with blogging (obviously), as we all are and, like many grad students, have been published more online than in print. I love the idea of sharing my thoughts and knowledge with others without worrying so much about polishing them into full-blown articles. Fitzpatrick’s idea of watching a project develop over time is an appealing notion because it gives you a more three-dimensional sense of a scholar and allows you to see the different angles of his or her interests. I also think the immediacy of the internet can be an incredible benefit if used with caution. Sometimes the process of conventional publication takes so long that the information can be all but obsolete by the time it reaches the people who need it. I also like that I don’t feel like I have to make any ground-breaking claims when I share this information. Many of my fellow bloggers have written on very similar topics in the last year, and many other forums of all different kinds have discussed the idea of digital authorship. But we don’t all read every blog out there (couldn’t, in fact), so ideas of absolute originality are a little more fluid. I will not claim to be saying anything completely new here. And that’s okay! I love reading blogs as well as contributing to them for all of these reasons.

Two important questions pertaining to grad students came up during Fitzpatrick’s informal seminar. The first engages with the amount of prestige required to take risks like digital publishing in academics and to convince a conventional academy that such online contributions count towards anything. As we all know, grad students have no prestige. Should we be taking these risks in such a tenuous job market? Should we be putting energy and time into online projects and collaborations if it could be spent on more conventional types of publication? All the “self-help” books on grad school, academics, and writing for publication that I’ve read have either ignored the possibilities of the online world altogether or advised young academics to stay away from them because they don’t “count.” Certainly, there are many problems with being able to publish anything instantly, the least of all being plagiarism, quality control, and authority. It’s refreshing and comforting to hear an established academic say that, yes, blogs and online publications can count and count for quite a lot at that. As Fitzpatrick says, reading, commenting, and keeping up with blogs and other online forums is also time-consuming and a lot of work, but these communities couldn’t exist without the interactive, conscientious, “peer” participant. We all, even by the act of sharing and commenting on online work, claim some part in its continued existence. Such activities create a new kind of credit for work by helping to get a writer’s name out there and recognizable, which can open up so many other opportunities. These kinds of activities should be taken seriously because they are serious! That being said, they are still not taken seriously on a job application, which, as I understand it, still credits conventional print publication (in addition to many other things, of course) and will do for quite some time. Fitzpatrick’s advice is to work towards a balance of traditional and more innovative publications and academic activities: online exposure can lead to name recognition, but it all comes down to that C.V.

engages with the amount of prestige required to take risks like digital publishing in academics and to convince a conventional academy that such online contributions count towards anything. As we all know, grad students have no prestige. Should we be taking these risks in such a tenuous job market? Should we be putting energy and time into online projects and collaborations if it could be spent on more conventional types of publication? All the “self-help” books on grad school, academics, and writing for publication that I’ve read have either ignored the possibilities of the online world altogether or advised young academics to stay away from them because they don’t “count.” Certainly, there are many problems with being able to publish anything instantly, the least of all being plagiarism, quality control, and authority. It’s refreshing and comforting to hear an established academic say that, yes, blogs and online publications can count and count for quite a lot at that. As Fitzpatrick says, reading, commenting, and keeping up with blogs and other online forums is also time-consuming and a lot of work, but these communities couldn’t exist without the interactive, conscientious, “peer” participant. We all, even by the act of sharing and commenting on online work, claim some part in its continued existence. Such activities create a new kind of credit for work by helping to get a writer’s name out there and recognizable, which can open up so many other opportunities. These kinds of activities should be taken seriously because they are serious! That being said, they are still not taken seriously on a job application, which, as I understand it, still credits conventional print publication (in addition to many other things, of course) and will do for quite some time. Fitzpatrick’s advice is to work towards a balance of traditional and more innovative publications and academic activities: online exposure can lead to name recognition, but it all comes down to that C.V.

One of the online authorship issues that grad students in my department have been worried about is the potential complications caused by publishing dissertations online, and this was our second question. Our university automatically publishes all dissertations (and theses) in an online, open access depository, with the option of a one-year embargo. We’ve been concerned about the possibility of being denied publication because our work would already be available through this open access forum, and we have heard horror stories of this happening. One year is certainly not long enough to get something published. However, Fitzpatrick posits this as another positive opportunity to get your name out in order to lead to other publications. I, myself, have cautious, mixed feelings about this related again to prestige qualifiers. I’d be interested to hear what others think about the idea of mandatory open access and what discussions have occurred in your departments about it.

The relationship between academics and digital possibilities is a huge and ongoing conversation, and I’ve really only summarized the ideas Fitzpatrick shared with us and added a (very) few of my own anxieties about online academic networks and forums. I’d like to end by inviting you to participate in this conversation with me. What have you heard about the pros and cons of online publications, blogs, and forums? How much do you value your own participation in such forums as either readers or participants? And the big question: how do we get such activities to “count,” IF we think they should count, in our current positions as grad students? What other issues complicate this question for you?

Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s Blog

Call for NGSC Bloggers 2013-2014

NASSR Graduate Students and Advisors of Romantic Studies Graduate Students:

The NASSR Graduate Student Caucus (NGSC) invites applications for new bloggers for the 2013-2014 academic year. We ask that NGSC bloggers commit to contributing about 1 post per month (or approx. 8-10 total per year) and to serving through September 2014.

To apply, please submit a short statement of interest, along with a current academic CV to: JacobLeveton2017@u.northwestern.edu. Applications are due on 23 September 2013. Applicants will be notified by 1 October 2013.

As always, we welcome posts on a wide range of topics and issues of importance to our authors that represent their range of expertise, scholarly experiences, institutions, research interests, and issues relating to student life.

Importantly: Posts need not be works of honed researched scholarship and sustained argument (though, admittedly, this can be a tough habit to break!). Posts can be as brief as a paragraph or as long as a few pages. Posts can also be a collage of images as well as thought experiments, original poetry, or a recently read poem or literary excerpt, or artistic piece or performance that you would like to share. Collections of links, reports on travel, or summaries of scholarly talks attended related broadly to the field of Romanticism are likewise warmly invited.

We hope this space is one where we can enjoy writing fun, lighthearted reflections or humorous quips as well as serious contemplations about our field. Fostering a supportive and meaningful community of graduate students is at the heart of this successful enterprise; we hope you will choose to take part!

If you have any questions about blogging for the NGSC, please send us an email and we’ll get right back to you.

Sincerely yours,

Kirstyn Leuner (Dept. of English, CU-Boulder), Chair, NASSR Graduate Student Caucus, and Co-Editor of NGSC blog

Jacob Leveton (Dept. of Art History, Northwestern U), Managing Editor, NASSR Graduate Student Caucus Blog

"Researching in Archives" – The NGSC Roundtable at NASSR 2013

Want to go on a funded research trip to study a collection that is crucial for your project? Want to know how senior scholars find funding, manage their time, and use a new collection to fortify their work-in-progress? Attend this year’s NGSC professionalization roundtable and learn how.

Conducting research in an archive away from your home institution can lend truly original ideas and evidence to your writing projects. It can also add important lines to your CV and prove that you have research skills that are important for the job market.

When: Friday, August 9, 11:30am – 1pm (Note: this is a brown-bag lunch session. Bring your lunch with you!)

Where: Conference Auditorium

We invited five distinguished speakers to give us advice on how to select an archive to travel to, get paid to do research there, and make the most of what we discover. Following short presentations we will open the floor for a lengthy Q&A session and conversation. Bring your lunches and your questions — we hope to have a lively discussion.

Speakers:

- Andrew Burkett (Union College)

- Jill Heydt-Stevenson (CU-Boulder, NGSC faculty advisor)

- Michelle Levy (Simon Fraser U)

- Devoney Looser (Arizona State U)

- Dan White (U of Toronto)

Specifically, our panelists will help us learn:

- how to write a winning application for funding for the trip,

- where major collections for our field are held,

- what you need to prepare before you arrive,

- how to use the archive as a place of discovery, and

- what to do with all the notes and photos we gather.

See you all there!

Save the Date: "Emerging Connections," A Graduate Professionalization Workshop. June 12, 2014, Tokyo, Japan

Leading up to the NASSR supernumerary conference “Romantic Connections,” graduate students working in the field of Romanticism are invited to attend “Emerging Connections,” a skills and professionalization workshop to be held Thursday, June 12, 2014, at the University of Tokyo.

This one day event is intended to give graduate students a chance to network with other students from around the world, and hear from guest speakers about a range of topics concerning the current state of the field and how best to navigate it as an emerging scholar.

Topics covered will likely include publishing, conference-going, job applications, and interviewing; we welcome graduate students at any stage of their degrees. We also hope to arrange some cultural events and tours of Tokyo. We are committed to keeping this event affordable and accessible to graduate students; detailed cost information will be available in the fall.

A limited number of rooms will be available in university accommodation for students attending this event and the following “Romantic Connections” conference (which runs from 13-15 June). There is also reasonably-priced private accommodation in the area ($50-$100 per night). Registration for this event will open this autumn along with the main conference. For more information, see the “Travel” section of the Romantic Connections website (http://www.romanticconnections2014.org/travel.html). Early registration is advised.

More details, including a list of speakers, will be available in the coming months, but to give us a sense of what kind of numbers we might expect, we’d love to hear from anyone who is interested in this event. Please email emergingconnections@romanticconnections2014.org if you would be interested in attending, and feel welcome to also suggest any topics you would like to see addressed.

Sincerely,

Danielle

Digital Humanities: My Introduction 1.2

This post is part two of a three-part series charting my introduction to the digital humanities. My entrance largely follows from attending a seminar that meets twice a quarter on Saturday mornings entitled, “Demystifying the Digital Humanities” (#dmdh). Paige Morgan and Sarah Kremen-Hicks organize the seminar and it is sponsored through the University of Washington’s Simpson Center for the Humanities.

The first post in this series attempted to define the digital humanities by considering some of its values. Today I want to make two points regarding what a digital humanist is and does. First, a digital humanist is not the same thing as a scholar. While the same person may occupy both roles, these roles nevertheless perform distinct tasks. Second, the digital humanist is distinguished by the tool set, and those tools are primarily for the purposes of visualization. So let’s explore these two points in greater detail, and I’ll conclude by looking at one of the many tools you can use in your own introduction to the digital humanities.

Tools, Tools, Tools!

On the last day of our Demystifying the Digital Humanities seminar (May 4, 2013), the organizers drew our attention to something surprising with regards to digital humanities scholarship: it may not be scholarship, at all. Many of those coming to the digital humanities already know how to conduct research, build and organize an archive, and employ “critical thinking” in order to arrive at some conclusions. The final step is often a presentation of these conclusions in the form of a written essay or a book.

Rather than adding data and conclusions in the scholar’s process, the digital humanist multiplies the perspectives and the media. The digital humanist uses tools in order to view and present collected data in the form of a diagram, graph, word cloud, map, tree, or timeline (or whatever you invent). Because a visual image allows us to see the “same” object or data set in a different way, the tool increases the scholar’s range of conclusions. So the scholar must demonstrate significance, but it is the tool that functions as a “bridge” for the sake of achieving that end.

Given the literary scholar’s tendency toward close reading, certainly an abstract diagram of the work(s) will lead to a less insightful reading. But here we are operating as if the tool provides a conclusion, which is the wrong assumption. The tool does not provide conclusions. The tool only allows us to see more at once.

My close reading of a romantic poem might be the most accurate, interesting, or revealing, but if I can see the same information in relation to more texts, across spatial and temporal fields, my tools will make conclusions regarding historical time periods outside my area of specialization. Wrong again! The map or graph only demonstrates correlations, intersections, and divergences. It is then up to the scholar to investigate those areas.

As the historian Mills Kelly says in his contribution to Debates in the Digital Humanities, “instead of an answer, a graph…is a doorway that leads to a room filled with questions, each of which must be answered by the historian [or literary scholar] before he or she knows something worth knowing.”[i] In this sense, the diagram functions like a treasure map that makes the X’s more explicit. And while that map will tell a scholar where to dig, it cannot tell us why the artifacts matter, what they mean, or how they are useful.

If the burden of the conclusion falls on the scholar, the digital humanist has aesthetic and logistic responsibilities. The digital humanist might ask questions like, “What kind of visualization most effectively represents my data?” It will also be important to consider financial issues like cost and maintenance. Often times, visualization software is free. But when depending on others for your tools, there are risks like the issue of ongoing support. If I use an online tool made by a company that suddenly “disappears,” I may have to go shopping. And let’s not forget the attachment people feel for an accustomed piece of equipment. Whatever tool one chooses, the old rule applies: backup your files. If you lose a tool you have only lost the medium through which you represent your information. Lose your information, and—well…

But everything we do comes with risks. To balance your decision as to whether or not you want to use these tools, I suggest having some fun with them first. An easy and fast way to see the benefits yourself is through IBM’s Many Eyes, a website devoted to free visualization software. The disadvantage is that Many Eyes’ visualizations must remain online; on the other hand, the site is so easy to use that you can test the water within minutes.

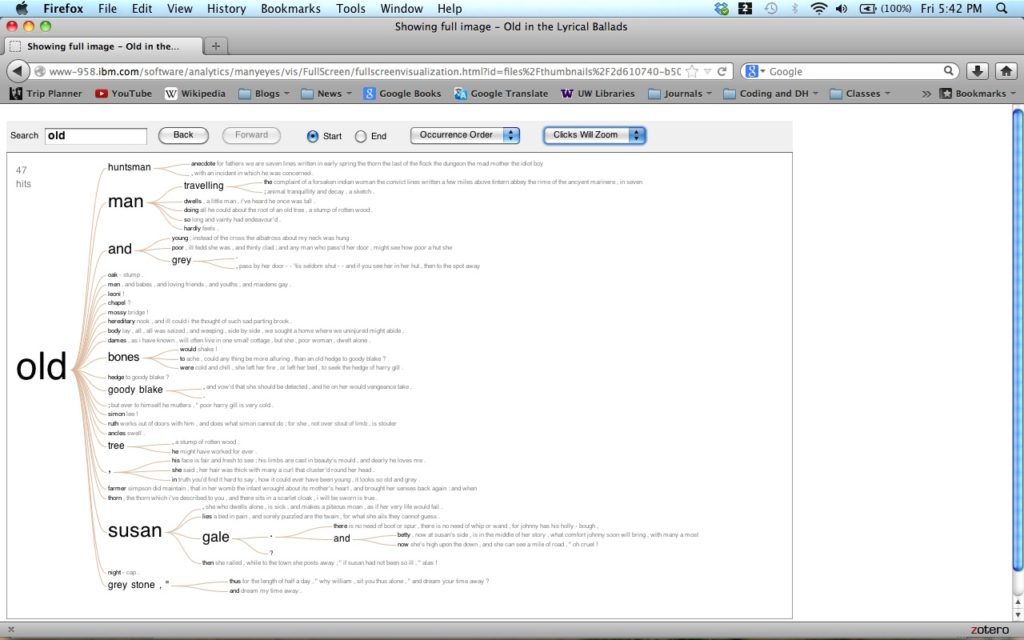

Below is a screenshot of a word tree I made from the Lyrical Ballads. In order to generate the tree, first I use the browser in the “data sets” to find the Ballads, which someone had already uploaded. Then I click the “visualize” button and select the first diagram option, “word tree.” From here I can enter any word from the Ballads that I want to explore. The 1800 edition begins with an “old grey stone,” so I enter “old,” which catches 47 hits. A diagram appears illustrating all the instances of “old” and how it connects to the words around it. Now imagine doing this with hundreds or thousands of texts. Many Eyes won’t tell you what all those connections mean; rather, it allows you to see them in the first place.

For a closer look at this image, click here.

Rather than “new,” the word that best describes the advantage of digital tools is “more.” A Concordance to the Poems of William Wordsworth does something very similar to my word tree above because the book also supplies all the instances of “old” in Wordsworth’s poetry. But with digital tools, I could add the concordances to Virgil, Spenser, and Milton, as well as those writing manuals, law documents, and political pamphlets. Then all of these texts can be incorporated into the same visualization. In a way, these possibilities make me less nervous about the future of scholarship. Now I can see more ways of lengthening the narratives I was already generating, and find more to explore.

Beyond aiding our own scholarship, the visualization helps communicate what we do as scholars to a broader audience. The thing to remember is that the tool is not a justification in itself and it does not make one’s role as a scholar more relevant. But with these tools we can better demonstrate the power of the media we study to others using a medium held in common across discipline lines. Equally important, by working with these tools, we are in a better position to illustrate the necessity of the scholarship that actually makes these images meaningful.

The Demystifying the Digital Humanities seminar ended last week, but I hope that Paige and Sarah are able to continue these valuable workshops in one form or another in the years to come. For my final post in this series, I will discuss how I have attempted to incorporate the digital humanities into the course I am teaching this term, some of my success, as well as my failures.

Alt-Ac-Attack: Thoughts on Preparing for the Job Market

The job market is not great right now. We all know it. We don’t always want to think about it. And, since several years pass between the first year of grad school and the last year, it’s very easy to avoid thinking about it: just put your nose to the dissertation grindstone until that last frantic year when you have to look up from your work and look around. The market can change a lot in five, six, seven years as well: when I left undergrad in 2006, it wasn’t horrible. Now… it is, and it seems like grad programs are realizing this and making moves to address it. We are just starting to really assess this issue in my own department, and we’re trying to do this in two related ways: focus on preparations for the academic job market earlier in a student’s career AND accentuate other options that we’re not often taught to consider: alternative academic careers, in other words. In this post, I’d like to describe some of the issues and possible positive practices we discussed in a recent meeting among grad students in my department. I’d also really like to start a dialogue about what other departments are doing to help their graduates prepare for a more positive future after all their hard work.

about it. And, since several years pass between the first year of grad school and the last year, it’s very easy to avoid thinking about it: just put your nose to the dissertation grindstone until that last frantic year when you have to look up from your work and look around. The market can change a lot in five, six, seven years as well: when I left undergrad in 2006, it wasn’t horrible. Now… it is, and it seems like grad programs are realizing this and making moves to address it. We are just starting to really assess this issue in my own department, and we’re trying to do this in two related ways: focus on preparations for the academic job market earlier in a student’s career AND accentuate other options that we’re not often taught to consider: alternative academic careers, in other words. In this post, I’d like to describe some of the issues and possible positive practices we discussed in a recent meeting among grad students in my department. I’d also really like to start a dialogue about what other departments are doing to help their graduates prepare for a more positive future after all their hard work.

Alt-ac jobs unjustly get a bad rap: they’re spoken of with low tones, shaken heads, shrugged shoulders. We’re so focused on getting that increasingly unrealistic tenure-track professorship that anything else seems like some kind of failure. And it really, really shouldn’t. Jobs are hard to get in many professions, but variations using the same skill sets don’t seem to be looked down upon as much as they currently are in academia. So, one of the first problems to be fixed is this negative attitude towards jobs that require exactly the types of abilities at which we excel, jobs that would provide financial stability, health care, productivity, and a lot of genuine happiness. Concerns that interfere with considering these options early might include support from the department, committee expectations, discussions (or silences) amongst fellow grad students about such subjects, as well as simple confusion about how to market skills we already have or even how to find alternative career options. All these problems are fixable. My department has taken a first step by putting a recently-hired faculty member in charge to act as a go-to person to help students on an individual basis as they approach graduation as well as to hold various workshops and meetings related to academic and alt-ac job concerns. Overall, we’ve discussed some New School-Year’s Resolutions as we round out the end of our current semester:

Alt-ac jobs unjustly get a bad rap: they’re spoken of with low tones, shaken heads, shrugged shoulders. We’re so focused on getting that increasingly unrealistic tenure-track professorship that anything else seems like some kind of failure. And it really, really shouldn’t. Jobs are hard to get in many professions, but variations using the same skill sets don’t seem to be looked down upon as much as they currently are in academia. So, one of the first problems to be fixed is this negative attitude towards jobs that require exactly the types of abilities at which we excel, jobs that would provide financial stability, health care, productivity, and a lot of genuine happiness. Concerns that interfere with considering these options early might include support from the department, committee expectations, discussions (or silences) amongst fellow grad students about such subjects, as well as simple confusion about how to market skills we already have or even how to find alternative career options. All these problems are fixable. My department has taken a first step by putting a recently-hired faculty member in charge to act as a go-to person to help students on an individual basis as they approach graduation as well as to hold various workshops and meetings related to academic and alt-ac job concerns. Overall, we’ve discussed some New School-Year’s Resolutions as we round out the end of our current semester:

Start early. As I said, it’s really easy (and, let’s face it, enjoyable!) to get wrapped up in your research and to forget about where it might lead you after graduation. I, myself, am incredibly guilty of this. Just starting to poke around at what jobs are available from time to time can create awareness (without panic) and can also give you a sense of the timeline for applying to various positions. Start making the most of what you’re doing right now. Have faculty come observe your teaching in preparation for letters of recommendation. Get involved with committees in which you may already have an interest. Use summers to explore short-term alt-ac jobs that might require editing, grant-writing, teaching, etc.

Know what we have. We have so many skills that would make us fantastic professors. But they’d also make us lots of other fantastic kinds of professionals. We can speak in public and plan lessons and manage groups of people and think on our feet and make information interesting and read large amounts and synthesize and simplify and summarize and analyze and explain and entertain and proofread and edit and a hundred other things. But we don’t always translate what we do into these broader skills. Some of the future workshops we’ve discussed focus on this kind of translation: how to recognize our skills, how to use our writing skills for different types of writing, how to change a C.V. into a résumé, etc.

Speak and listen. Half the problem with both the impending trauma of the job  market and the search for alt-ac jobs is that we don’t talk enough about them. We don’t talk about what we think about putting our skills to use in different ways, and we don’t discuss what those different ways might be. What we’ve done, just by having a meeting to discuss the new faculty position and what we’d like it to cover, is to allow ourselves to talk and to listen to one another. This is huge. What’s more, we’re hoping to be able to speak and listen to those outside our current student and faculty population by contacting alumni who have pursued various career options with our same educations. We’ve begun to bring in speakers who can help us think about aspects of professional development and alt-ac careers. We’re planning mock interviews and job talks amongst ourselves, as well as more informal discussions about other aspects of applications.

market and the search for alt-ac jobs is that we don’t talk enough about them. We don’t talk about what we think about putting our skills to use in different ways, and we don’t discuss what those different ways might be. What we’ve done, just by having a meeting to discuss the new faculty position and what we’d like it to cover, is to allow ourselves to talk and to listen to one another. This is huge. What’s more, we’re hoping to be able to speak and listen to those outside our current student and faculty population by contacting alumni who have pursued various career options with our same educations. We’ve begun to bring in speakers who can help us think about aspects of professional development and alt-ac careers. We’re planning mock interviews and job talks amongst ourselves, as well as more informal discussions about other aspects of applications.

The job market is a sensitive subject for practically everyone right now, particularly for academics who have invested so much time and energy into a very specific career path. Yet, it’s also a concern near and dear to our hearts as we watch friends and colleagues struggle and prepare for struggles of our own. I am incredibly pleased and proud to be part of these steps to create a space for such an important conversation.

But, I know we are certainly not alone. I’d really like to open up this discussion to my fellow blog-readers: what steps have your departments taken to think about the job market and alt-ac careers? What have you found useful or frustrating in regards to the leap from graduate student to job seeker? What have you found really helpful in this process?

Helpful resources:

Digital Humanities: My Introduction 1.1

For those who have yet to drink the digital humanities “Kool-Aid” (it’s the blue stuff they drink in Tron), for the next three posts I will chart my own introduction. My entrance largely follows from attending a seminar that meets twice a quarter on Saturday mornings entitled, “Demystifying the Digital Humanities” (#dmdh). Paige Morgan and Sarah Kremen-Hicks organize the seminar and it is sponsored through the University of Washington’s Simpson Center for the Humanities.

For those who have yet to drink the digital humanities “Kool-Aid” (it’s the blue stuff they drink in Tron), for the next three posts I will chart my own introduction. My entrance largely follows from attending a seminar that meets twice a quarter on Saturday mornings entitled, “Demystifying the Digital Humanities” (#dmdh). Paige Morgan and Sarah Kremen-Hicks organize the seminar and it is sponsored through the University of Washington’s Simpson Center for the Humanities.

In this post I want to outline a brief definition of the digital humanities, and I will conclude by suggesting some things that you can do to advance your own understanding. Because these posts stem from my own introduction, they might be too basic for those already immersed in DH studies. Rather than an in-depth exploration, consider this post as an enthusiastic sharing of information.

Defining the Digital Humanities

During the first session of the seminar we attempted to define the digital humanities. A typical strategy towards definition might ask what a concept “is.” But the organizers challenged us to think about what this concept “does” and what “values” it embodies. The next two installments of this series will cover what you can “do” in the digital humanities. Today, I want look at some values.

Collaboration is one of the main values espoused in the digital humanities. “Instead of working on a project alone,” as Lisa Spiro says, “a digital humanist will typically participate as part of a team, learning from others and contributing to an ongoing dialogue.”[i]

In which case, a digital humanist might post his or her most recent progress, research, or problem on a blog or Twitter feed. Others can then add comments, suggestions, and criticisms. There is also a push toward finding people with the resources to do the job you have in mind (knowing he had the skills, I asked my brother to make the image above for this post). Overall, there is a common avowal among digital humanists that works ought to receive input and support from others before reaching the final product, and in addition, this feedback can come from more people from different disciplines.

Making works more available, as Paige and Sarah stressed, also means a greater willingness to be “open,” even with regards to “failure.” By being more open scholars can overcome the erroneous belief that every “success” equals “positive results.” As in the physical sciences, in the humanities there is little sense in reproducing the same bad experiment more than once. Sharing failures might ultimately lead to less repeat, and potentially more success.

It would be impossible to offer a full definition in this short space, but my conclusion so far is that, without knowing it, many young scholars are already invested in the digital humanities. For instance, writing for the NASSR Graduate Student Caucus blog qualifies as a digital humanist platform and method. I am writing in a public domain, making my interests more open for sharing and criticism, taking risks on what kinds of content I post, and focusing on producing more products more consistently, all of which embodies a DH ethos. During the first seminar in October, upon learning that I already shared many digital humanist values, it encouraged me to go familiarize myself with some of the tools, which I will now discuss.

Getting Started in the Digital Humanities

While not every university hosts a seminar like the one I attended, there are some traveling ones. According to the THATCamp homepage, it is “an open, inexpensive meeting where humanists and technologists of all skill levels learn and build together in sessions proposed on the spot.” These camps take place in cities all over the world and anyone can organize one. Or if you want something more intense, try the Digital Humanities Summer Institute at the University of Victoria (see Lindsey Eckert’s post on this site for an overview).

If you really want to jump into the digital humanities fast (this might sound self-indulgent in this context), I think the best method is reading blogs. The problem with blogs is the sheer quantity. But once you find a blog that works, they usually provide a blogroll that includes a list of the author(s)’ own preferences. At the bottom of this page I provide three blogs with three different emphases regarding the digital humanities for you to try (and please respond below if you have others to suggest).

The last thing is coding. It seems scary, but with simple (and free) online tutorials, learning how to code is like getting started with any foreign language: the first day is always the easiest. You learn “hello,” “please,” “thank you,” und so weiter. The difficulties arise later. But anyone who has travelled abroad knows that a small handful of phrases can actually satisfy a large range of interactions. For instance, it takes a few minutes only on w3schools.com to learn how to make “headings” in your blog post (like the emboldened titles above). Headings actually allow search engines like Google to more easily recognize your key words and phrases, which I didn’t realize until I started learning a little code. Ultimately, learning how to code can help you appreciate the rules that govern your online experience.

Last, I think it’s important to divulge why I became interested in the digital humanities. Because my dissertation started to focus more on tools, geometry, and the imagination in the eighteenth century, I found myself on the historical end of digital space. It made good sense then to start exploring current trajectories. But as I hope to show in the next two entries, “doing” digital humanities does not necessitate digital humanities “content.” Your introduction might be more about method, pedagogy, or even values. That said, it is worth having a good reason to invest your time in DH studies. As graduate students, time is always in short supply. But if it’s the right conversation for you, be open, be willing to fail, and enjoy the Kool-Aid.

Some Suggested DH Blogs:

If our blog is the only one you are reading with any frequency, perhaps the next place to go is The Chronicle of Higher Education’s ProfHacker. This blog features a number of authors writing on the latest trends in technology, teaching, and the humanities. For starters, try Adeline Koh’s work on academic publishing.

Ted Underwood teaches eighteenth and nineteenth century literature at the University of Illinois. His blog, The Stone and the Shell, tends to explain DH tools, values, and protocols for “distant reading.”

For a more advanced blog, in terms of tools and issues, I have found Scott Weingart’s the scottbot irregular resourceful, interesting, and it is also a great example of how to up the aesthetic stakes of your own blog.

Dialectical Effusions, or Why I love the Romantics – Part II

So, without further adieu, I will discuss the two working axioms and further elaborate on my reasons for loving the Romantics.

1. They were audacious and/or eccentric (perhaps I should just say “outrageous.”)

Some representative statements and exploits should suffice.

- Coleridge and Southey‘s desire to establish a pantisocracy in America. Who does this? But how noble and grand that before Marx, some people did (or proposed doing it): an egalitarian commune. Wow. And these people are those we now call the Romantics.

- Coleridge on Hume (after the young Hazlitt asks for his take): “‘Hume? He stole his essay on miracles from South’s sermon!’ replied Coleridge. ‘He can’t even write. He’s unreadable’” (Wu 6). Yes, one of the 18th century’s greatest philosopher is summarily dismissed by the young Coleridge. Only someone with immense belief in their own talent would say such a thing and at the end of the 18th century when Hume’s status as a world-class philosopher was by then established.

- The actress and writer Mary Robinson’s outrageous dalliance with the teenaged prince regent. Playing the role that made her famous, Perdita, in an adaptation of The Winter’s Tale, she speaks the following lines at a royal command performance: “… how to put on/This novel garment of gentility…/ …I shall learn/ I trust I shall with meekness, and an heart/Unalter’d to my Prince, my Florizel.” (Byrne 99). Her performance draws tears from the prince, as well as several bows–and his heart. After suffering bad press (though her ability to manipulate it was uncanny) due to her romantic attachments to the prince and to other powerful men (whom, it does not appear, the press smeared for their indiscretions though certainly for their politics), she is audacious enough to re-invent herself as a master poet and novelist. Of her, Coleridge said, “She is a woman of undoubted Genius…I never knew a human Being with so full a mind” (Byrne Epigraphs). From one genius provocateur to another.

- Lady Caroline Lamb, the ultimate femme fatale. She is known for writing the famous lines that have immortalized Byron: “[He was] mad, bad, and dangerous to know” (Hay 13). After their romance comes to an end (for Byron, that is) the aristocratic Caroline will not be ignored *cue Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction*. She forcefully makes herself known by breaking in to Byron’s residence and inscribing the following words in his copy of Vathek (an action filled with significance given Byron’s championing and practice of Greek Love and Beckford and his novel’s notoriety): “Remember me! Remember me!” Oh, and she also writes the novel Glenarvon–the titular character is a Byronic hero who is actually based on Byron…(wait, how does that work?)–quite possibly the first tell-all book written in the Gothic mode. Byron claimed that, upon her betrayal of him, he would pursue Caroline like Falkland had pursued Caleb. It appears that Lady Lamb turned the tables on this scenario.

- Claire Clairmont, the not-so-famous family member (but look at the competition, though). I had always assumed she had been introduced to Byron by Mary and Percy in Switzerland but no: she wrote him before the famous trip. In an intrepid fan letter to Byron, the eighteen year old Claire commits the following lines to paper: “If a woman, whose reputation has yet remained unstained…if with a beating heart she should confess the love she has borne you many years…if she should return your kindness with fond affection and unbounded devotion could you betray her, or would you be as silent as the grave?” (Hay 78). He takes her up on her offer, though I’m not sure he didn’t betray her. But still, her letter and its fine sentence constructions render her boldly interesting.

2. They were pretty good writers too.

Whatever the criteria used to establish literary merit, their writing can be sharply ironic, lyrical, polemical, rhetorically persuasive, and often multi-generic. I’m not saying that each Romantic writer totally evinces these qualities (though I think some do) but, certainly, each exhibits mastery of at least one genre, if not two (or more). And even those that are associated with one genre, such as Wordsworth (though the 1802 Preface is pretty masterly as an essay if you ask me), are top-notch in that genre. As such, on any given day, I read the Romantics purely for their aesthetics or politics, though when writing papers, for both. But the point is that their writing is always engaging, wholly absorbing, whatever its genre, content, and politics.

(Is there an un-interesting Romantic writer? I’ve yet to find her or him. Let me know, though I suspect whoever this enigmatic figure is, something of major interest will be found in terms of their biography, writing, or political affiliations, watch.)

Politics: Conservative or liberal, Tory or Whig, the manifest political tendencies in the writing of several authors show Romantic writing to be irrevocably enmeshed with the political concerns of its day. Whether we are discussing Burke’s defense of the French monarchy (all monarchy, really) or Wollstonecraft’s Reflections on the Revolution in France or Byron’s impassioned poetic defense in “Song of the Luddites,” the intersection between history, polemical writing, and aesthetics is tightly welded together: one cannot have one without the others.

Lyricism: I was struck by Wordsworth’s lyricism. Now, I know about the sort of anti-Wordsworthian turn in Romantic studies (or so it seems to me). Or, I think scholars are perhaps reacting to the once powerful, institutionally-sanctioned equivalence between Romanticism and Wordsworth (or any of the Big Six at different times). I get it. But still. Never mind his so-called “conservative turn”: his poetry is so lyrical. The first lines of the Intimations Ode are etched in my memory: “There was a time when meadow, grove, and stream…did seem/apparell’d in celestial light….” And it gets better: “Whither is fled the visionary gleam? / Where is it now, the glory and the dream?” Wow. This longing for the luminosity of the past. Beautiful. (And I’m aware of the French Revolutionary undertone but, nevertheless, I still sometimes just want to read it for its cadence and beauty, its power to stir something melancholy and ineffable in me…) And I am one to be seduced by style, easily, as my obsession with Ayn Rand in my early twenties proves. She, by the way, wrote a book titled The Romantic Manifesto…talk about misreading (though Rand and my eventual turning from her writings and teachings are subjects for another day. Suffice to say that I do not consider her a Romantic nor do I now consider myself a Randian.)

Anyway, to conclude I’ll say that as with all obsessions, scholarly and otherwise, I believe they originate in some primal scene, in a trauma experienced during one’s formative years. Discussing what such primal scenes might be in my life are beyond the scope of this blog, though I have no aversion to discussing them—ask me at a conference sometime. I will say, however, that I am continually propelled and assailed by contradictions, that is, I am almost always besieged by contradictory impulses. For instance, some days, I want to live in a world where transcendence is possible. On such days, I happen to believe in extraterrestrials and want to experience what some UFO specialists designate as Theophony (a connection with all and with God) which occurs in one of the stages following an alien abduction. I’ve even thought about camping out and keeping a night’s watch for sight of aliens. I sometimes converse with my ancestral deity, Ometeotl Moyocoyani (“He who invents or gives existence to himself”), as if I were chatting with my neighbor about the weather. And I’ve also thought about reading Hermetic scrolls in order to discover the ritual, symbolic steps I need to take in order to lose consciousness of myself while entering into communion with the plenitude of the Universe. Transcendental knowledge. Yes, I seriously have thoughts about this. And, so, there are the Romantics whose lyricism and content provide somewhat of transcendental moments.

On other days, the political unconscious aggressively asserts itself: not only Romantic texts but also newspaper headlines, advertisements, the idea of transcendence, and the unjust social order all scream out their ideological construction. It is with Jacobinical fervor that I begin to re-focus on political and economic crises and on the privations suffered by various underclasses. When I do, my pursuit of transcendence seems a tad misguided and quietistic. I struggle, always, with my decision to pursue graduate school while several communities I hold close to my heart continue to struggle, while I’m writing seminar papers on Percy’s “Alastor”. But I’m ok with this. Now. And this is because the Romantics are (incredibly!) with me on all these issues, as well. In fact, I audaciously venture to say that the Romantics speak not only to these contradictory impulses but to every desire (earthly or transcendental), impulse (political or artistic), occurrence–momentous or mundane–under the sun.

Folks, I can’t wait to start the English PhD program this fall.

Works Cited

Byrne, Paula. Perdita: The Literary, Theatrical, Scandalous Life of Mary Robinson.

New York: Random House, 2004. Print.

Hay, Daisy. Young Romantics: The Tangled Lives of English Poetry’s Greatest

Generation. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010. Print.

Wu, Duncan. William Hazlitt: The First Modern Man. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

2008. Print.

Dialectical Effusions, or Why I love the Romantics – Part I

As a recently admitted student to a doctoral program in English, for my first blog I figured I would reflect on why I am pursuing the study of British Romanticism. Be forewarned: some of my reasons are un-academic, wildly emotional even, and in some ways flagrantly partake of the Romantic ideology (See McGann). But I’m ok with this.

I will organize my reasons for my love and pursuit of Romantic studies around two working axioms: 1) “The Romantics were audacious and/or eccentric” and 2) “Their writing is pretty good, too.” I will conclude by reflecting on my (almost) libidinal reasons for my attraction to the Romantics–(you have to read up to the ending, see?)

Before elaborating on each axiom, I will first discuss how I stumbled across the Romantics and then proceeded to fall wildly in love with them and their writing. As a junior Honors English major, I had a day left before deciding on an honors elective seminar. The following course title leaped out at me: “Sex, Drugs, and Rights: Experimentation in the British Romantic Era”–with a course title like that, who wouldn’t be immediately intrigued by the Romantics? I signed up right away. I showed up to class and we began to work our way through the “Rights” portion of the syllabus. We read William Godwin’s Caleb Williams and Mary Hays’s Victim of Prejudice against the backdrop of the so-called Pamphlet Wars: Burke contra the French Revolution, Wollstonecraft contra Burke, and so on. The idea that the political and the aesthetic and their intersectionality were at this period so urgently and publicly debated grabbed a hold of my imagination.

Moreover, being a double major in Chicana/o Studies, the idea that civil rights and reformist politics were not solely an American 1960s phenomenon, threw off my sense of a progressive sense of history–an aporia: before the 1960s, the British (of all people!), were in the vanguard of reform and demanding civil rights for women, the working class, etc? And as far back as the 1790s? The thought was staggering and led to more questions, one being: what happened to civil rights reform in England and the U.S. in the 1790s—1960s interval? These types of historical questions set the tone for the rest of the semester and have continued to inform my studies of the Romantics and of Civil Rights history & literature, generally. (I recently discovered the concept of “postmodern Jacobinism” in Orrin Wang’s Fantastic Modernity: Dialectical Readings in Romanticism and Theory which provided me with the means for theorizing the link between the French Revolutionary 1790s and the Civil Rights movements of the 1960s.)

We also read De Quincey’s Confessions and Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” and William Beckford’s Vathek. (Here, I will only discuss De Quincey). Wow. Though De Quincey’s elaborate and operatic drug-induced hallucinations fascinated me to no end, the first half of the book–the “sober” portion–also grabbed my attention. Here was this son of a merchant who though materially impoverished, knew his Greek and Latin (something he reminds his reader of continuously and at one point, I think, claims to know better than an uppity man of the cloth). De Quincey’s self-representations were contradictory but intriguing. On the one hand, he is quick to remind readers of his classical learning; while on the other, even as he strains to define himself against London’s lumpenproletariat, there is a sense of empathy for the disempowered, evidenced especially in his sympathy for his friend, the prostitute Ann, and for the orphan girl. Of course, his drug use and its mental effects were interesting too, filtered as they were through orientalia and grotesquely beautiful imagery, all interspersed with philosophical ruminations. All these elements combined to give a sense of a troubled but brilliant mind (his syntax was so fine, too, so precise yet poetic). In short, the class whet my appetite for more of the same: complex and disturbing political material packaged in pleasing (to me) aesthetic form.

After finishing up the class, I then took several other Romanticism courses (with Romanticist Ranita Chatterjee), such as a “The Construction of Romanticism: Wordsworth and Shelley” and “The Traumas of the Godwin-Shelley Circle,” and continued to read primary and critical texts during my free time. I read Percy’s “The Mask of Anarchy” and De Quincey’s satirical essay “On Murder Considered as a Fine Art.” As far as criticism, I perused sources diverse in their ideological orientation, such as Wang’s book, M.H. Abrams’s The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition, Frances Ferguson’s Solitude and the Sublime: The Romantic Aesthetics of Individuation, and Tilottama Rajan’s Supplement of Reading: Figures of Understanding in Romantic Theory and Practice. These not only helped me engage with the changing conceptions of what constitutes Romantic Literature but also to become aware of the extent to which critical methods enable these and other scholars to read, extend, and problematize Romantic Literature. It seemed to me that Romantic texts were somehow inherently capable of generating new readings, inexhaustible in their capacity to stretch and bend to the probing eyes of scholars who used novel theoretical lens.

Once, while reading Mary Shelley’s The Last Man under a canopied tree on my campus, I had the thought that Romantic Literature, through its aporias–in Mary Shelley’s novel, the narratological disjunction caused by the prologue which mentions that the “last” man’s ensuing narrative is edited by two tourists—was like this organic, mystical clay that continuously took on amorphous shapes, receptive to the critic-claymaker’s deft touch. Yes, I had this very strange thought that is very Romantic and a little screwy. (But it only certifies—makes me certifiable?—that I’m pursuing the right literary period.)

Romanticism, on a bad day, makes me grumble, “These interesting writers are nuts.” On a good day, reading these writers stimulates my own inner-Romantic lunacy.

Work Consulted

McGann, Jerome J. Introduction. The Romantic Ideology: A Critical Investigation. By McGann Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983. 1-20. Print.

Stay tuned for Part II…

Reading List Adventures

This is the semester I am struggling to put together my reading list for the comprehensive exams. I have to admit it’s a rather exhausting process, much more exhausting than I initially planned for. I entered into the PhD thinking I had a firm grasp on what I wanted to do – pursue eco-criticism and animal studies in Romanticism. I’ve found out that’s a rather hard thing to do. Going into a relatively interdisciplinary field requires a lot of thinking about different kinds of texts, themes, and theories. Anyone who has read texts dealing with race or gender will tell you that animal metaphors work to separate different kinds of people. So, are these metaphors in some way worth talking about, given their obviousness in the texts? In what ways do they change as the Industrial Revolution takes hold and separates, in a somewhat larger way, mankind from nature? The most important question (for me at this point, anyway) is how can I begin to get a hold on this issue in time to create a cogent and defined 120-odd booklist?

As I began working on it, I knew that environmental metaphors animated critical gender discussions in the Romantic era. In Vindication of the Rights of Women, Mary Wollstonecraft argues that women are poisoned by their own culture, “for, like the flower which are planted in too rich a soil, strength and usefulness are sacrificed to beauty.” Yet, “the perfection of our nature and capability of happiness” is partially based upon “man’s pre-eminence over the brute creation.” Those are obvious metaphors, but the way in which they position a woman in relation to the environment intrigues me. I thought about several canonical works from the period, and then I consulted several anthologies as well as these lengthy lists:

http://graduate.engl.virginia.edu/oralsonline/

http://www.columbia.edu/cu/english/grad_orals.htm

http://www.english.ucla.edu/index.php/Current-Students/graduate-reading-list

There’s a lot of texts on there, some that I was only peripherally familiar with and some that I had never encountered before. I looked for texts written by women or texts that dealt with the question of women that also involved the environment or animals. As you can imagine, that led to a rather long list filled with novels, poetry, plays, travel essays, literary essays, and theory tracts.

Then, I had a sort of revelation that I was not expecting and it came from an odd place. I began looking at pretty pictures of dresses.

Yes, you read that right. Pretty dresses. When it is winter and I feel bogged down by reading, and grading, and writing, I like to look at art, clothes, and houses from the period I study. It’s mentally invigorating, but that might just be an excuse I tell myself to look at beautiful dresses.

I noticed through my cursory searching a rather huge difference between women’s fashion pre- and post-Romantic Era fashion, especially in terms of how much of the body is shown and what is on the linen. Dresses changed from being highly structured and covered in flowers to being more flowing with less natural decorations. I am in no way claiming to be an expert on women’s fashion. How correct or incorrect these observations are is less important than the effect it had on my list-making. I began to wonder how animals and the environment were utilized to produce certain kinds of bodies. That began to narrow down my list, and it also gave me a clearer picture of what else to put into the list.

My advice for this whole process is pretty simple:

1.) Look around a lot. Consult examples of lists, anthologies, your Amazon wish-list. You’ll need to balance the canonical, but also find the exciting, bizarre, and strange you believe you might want to read.

2.) Be available for inspiration in whatever form it happens to take. Go to a museum. Go outside. Talk to your pet. Eat a good meal. Give your mind a moment to relax and you’ll find the Ah-ha!