Late eighteenth century physicians (for the most part) increasingly  embraced the wisdom of learning anatomy directly from a dissected corpse. Feeling the textures and depths of the body’s interior and seeing it all firsthand became an invaluable tool for beginning physicians. However, this method of teaching ultimately relied on the advancements in medical thought demonstrated in the sixteenth century by one man: Andreas Vesalius. The brief version of his contribution to this field is that he turned a system in which the physician dictated dissection from a space removed from the actual body, and a surgeon performed what he was told on the body. Physicians, in this system, rarely encountered the actual interior of the body. Vesalius changed all that. Not only did he dissect his own corpses, but, by doing so, he corrected many of the errors in previous anatomical texts based on an assumed closeness between human and animal anatomies. His most famous work is the beautiful, fully illustrated De Humani Corporis Fabrica (often referred to as just the Fabrica). You probably recognize the frontispiece pictured here. Continue reading “The Body on Display: A Day at the NYAM Medical History Festival”

embraced the wisdom of learning anatomy directly from a dissected corpse. Feeling the textures and depths of the body’s interior and seeing it all firsthand became an invaluable tool for beginning physicians. However, this method of teaching ultimately relied on the advancements in medical thought demonstrated in the sixteenth century by one man: Andreas Vesalius. The brief version of his contribution to this field is that he turned a system in which the physician dictated dissection from a space removed from the actual body, and a surgeon performed what he was told on the body. Physicians, in this system, rarely encountered the actual interior of the body. Vesalius changed all that. Not only did he dissect his own corpses, but, by doing so, he corrected many of the errors in previous anatomical texts based on an assumed closeness between human and animal anatomies. His most famous work is the beautiful, fully illustrated De Humani Corporis Fabrica (often referred to as just the Fabrica). You probably recognize the frontispiece pictured here. Continue reading “The Body on Display: A Day at the NYAM Medical History Festival”

Online and Off Kilter: Navigating the Online Classroom

In my composition class this semester, we’ve been talking a lot about education: teaching methods, evaluation, structure, etc. There’s a new documentary out called Ivory Tower, and, though I haven’t seen it yet, we read a few articles about it in class, like “The Hi-Tech Mess of Higher Education,” which links panic over the value of education to increasing emphasis on technology. It’s not new or surprising to say that online education is on the rise. More instructors are offering online classes, and more students are electing to take them. Not only will they allow you to pursue your education from anywhere with an internet connection, but many of them will allow you to have a flexible schedule as well. Personally, I will probably always prefer the traditional classroom setting (and my current students told me they would, too), but there are undeniable benefits to an online course, alongside many challenges for those of used to the face-to-face interaction with students and/or teachers. Continue reading “Online and Off Kilter: Navigating the Online Classroom”

In my composition class this semester, we’ve been talking a lot about education: teaching methods, evaluation, structure, etc. There’s a new documentary out called Ivory Tower, and, though I haven’t seen it yet, we read a few articles about it in class, like “The Hi-Tech Mess of Higher Education,” which links panic over the value of education to increasing emphasis on technology. It’s not new or surprising to say that online education is on the rise. More instructors are offering online classes, and more students are electing to take them. Not only will they allow you to pursue your education from anywhere with an internet connection, but many of them will allow you to have a flexible schedule as well. Personally, I will probably always prefer the traditional classroom setting (and my current students told me they would, too), but there are undeniable benefits to an online course, alongside many challenges for those of used to the face-to-face interaction with students and/or teachers. Continue reading “Online and Off Kilter: Navigating the Online Classroom”

Interview: Dr. James McKusick

One of Romanticism’s favorite ecocritics, Dr. James McKusick, explains how getting lost in the woods at the age of five helped inspire his brilliant book, Green Writing: Romanticism and Ecology. He shares, “I was playing with some friends and they went home. I went the other way and I was lost on my own for a couple hours. I finally found my way to a house in the woods, where there was this little, old lady, who decided not to make me into soup. She actually called up my friends’ parents, who rescued me. It’s one of those formative childhood memories. The takeaway is that I’ve always wanted to wander in wild places. It’s part of my makeup.”

Scholars of Romanticism should be thankful for a couple of things: first, that the old woman in the woods did not make McKusick into soup and, second, that the curiosity and bravery that five-year-old McKusick demonstrated in his exploration of the woods has grown and can be seen within his scholarly work in our field.

INTERVIEWER

How did you become interested in ecological approaches to Romanticism?

MCKUSICK

I’ve probably spent five years of my life out under the open sky. However, it never occurred to me that I could translate any of this into the practice of literary study or literary criticism until long after I was out of graduate school. My dissertation had nothing to do with wilderness—it had to do with the philosophy of language. It was only after I got tenure, on the basis of that work, that I put my head up and I said, “What do I want to study next?”

At that time, there was no such thing as ecocriticism. This was the late 80s, early 90s, and Jonathan Bate had just published his first book on Wordsworth and green Romanticism, but with that exception, there wasn’t that much out there in specifically the field of British Romantic or Transatlantic ecocriticism. Obviously, there’s a long and distinguished history of people who study environmental writing, especially in the American context. That’s really, I think, the center of gravity for the field of environmental writing. If you look at most anthologies of nature writing, they have to deal with mostly 19th-century essay writers, Thoreau, Emerson, and that whole tradition down to Rachel Carson and modern times. But what’s missing in that tradition is the deeper history that goes back to at least the Middle Ages, perhaps the Classical period. The deeper intellectual and spiritual history of nature writing is what I’m after.

There was just a morning when I woke up, and I had this Gestalt experience, where I said, “You know, I love wild, natural, places, I love literature, I want to bring those things together.” It made sense in terms of my own life journey, but it was also an edgier, more dangerous field to go into because there wasn’t such a field yet. I got to be in there at the creation, so to speak. Organizations such as ASLE were just starting to be formed […] There was an aha! moment as well, where I found the poetry of John Clare, a lesser studied British Romantic poet, who, especially at that time in the 80s and 90s, was virtually unknown to Americans. British scholars have always known about Clare, but they, perhaps, have not taken him as seriously as he should have been taken. They used to speak of poor Clare, the poor mad poet. They knew a few of his poems that he wrote in the madhouse, but they didn’t know the reams and reams of wonderful poetry that he wrote during the primary phase of his poetic career, when he was not in the madhouse, when he was just a peasant farmer living his life out under the open sky.

John Clare was an amazing discovery for me. I became well acquainted with the world’s leading scholar of Clare studies, Eric Robinson, who is also the main editor of Clare’s work. Eric became one of my great mentors […] Through the study of John Clare, I’ve come to a more comprehensive understanding of what environmental writing is or can be. What I love about John Clare is simply his authentic connection, his groundedness in a particular wild place. John Clare was there at a transitional moment in the history of British agriculture, when they were moving from the ancient common field system to the enclosed or private field system. He deeply mourned that transformation of the landscape. The enclosed fields were being intensively cultivated. It was kind of a green revolution in agriculture, which made the lands more productive, and, in a sense, industrialized the land. It also destroyed many of the wild creatures that lived there, their nesting places, their habitat. Clare was really the only person who seemed to care. It was a tragedy that affected the landscape, and this is all captured beautifully through Clare’s poetry, through the poetics of nostalgia. He writes about land the way it was, but he also uses the poetics of advocacy. He advocates for preserving the landscape and for the rights of the creatures that inhabit there. Clare’s poetry is either naïve or deeply, mystically, connected with the landscape. I prefer the second idea.

Discovering Clare was a huge milestone. My first article in ecocriticism was my article on John Clare and I had a terrible trouble finding anyone who would publish it because it was perhaps ahead of its time. There was something about it that didn’t sit well with the literary establishment. I finally published it with a literary journal out of Toronto […] That turned into a chapter in my Green Writing book, which probably took me ten years to write. I took my time with that book because I was discovering my methodology as I went along. There was no one I could sit at the feet of and learn how to do ecocriticism.

INTERVIEWER

What does an ecological reading open up about texts that other readings do not?

MCKUSICK

One of the real landmark pieces of work in ecological criticism has been done by Lawrence Buell. He addresses the question, “What is an environmental text?” The answer to that question is all texts, because every text has an environmental context. That environmental situation can be overtly expressed in the text or not […] If you just think of ecological criticism as “the study of nature writing,” it tends to marginalize it before you even get out of the starting gate. You’re only going to look at texts that are often in a fairly boring way describing “pretty things in the natural world.” There’s not really a lot to say about that, other than “how pretty!” That’s not what an ecological reading is or should be. What Buell teaches us is that every text has an environmental dimension. If it’s by a sophisticated writer, this dimension will be overtly manifested in the text in some respect.

We also need a broader understanding of ecology to realize that it is the study of everything that happens in the world. It isn’t just simply the study of wilderness, which is the other category mistake that people make in looking at ecological writing, the study of wilderness theory or wilderness areas. That’s a big piece of ecological criticism, but it is not the only piece. To be a good ecological critic, you need to look at urban as well as rural landscapes, land as well as ocean, and the sky is important. There’s nothing that gets left out of an ecological reading of a text. An ecological reading of a text can also poke at what is not there, what is not manifested in the text, but should be, or is repressed […] One of the best things about ecological criticism, I think, is that it is linked to a larger environmental movement that is gaining more and more headway in our larger society as we speak. To me, it seems a lot more authentic for literary scholars to be engaged in the struggle to protect the environment than it does for us deeply bourgeois professors to be involved in something we call the class struggle and the liberation of the common man. Somehow, that doesn’t ring authentic.

The other beautiful thing about ecocriticism is that it’s a methodology that has legs and can travel into any literary course, no matter the period or the genre or the subject matter under consideration. It can be used as a skeleton key to open up texts and see dimensions that our students truly care about. Our students care about sustainability, they care about environmental preservation. So I try to embed ecocriticism into any course that I teach. It also allows an interdisciplinary conversation to take place. If you have students from the sciences, or engineering, or music and theater, they can call relate to this content in a way that makes literary studies more relevant to their own individual circumstances […] Certainly, ecocriticism is not intended to drive out every other method of literary analysis. It is meant to complement what we already have. It’s another set of tools to put in the toolbox.

INTERVIEWER

Your book engages the idea of the pastoral, citing the 18th-century context of the construction of “English gardens’ that imitated the idyllic disorder of natural landscapes, rather than formal geometric patterns” and, from my understanding, trace how “a true ecological writer must be ‘rooted’ in the landscape, instinctively attuned to the changes of the Earth and its inhabitants” (20, 24). I’m struck by several things here. If true ecological writers must be attuned to the landscape, might we view them as a collector? And, if we can view them as a collector, how might we negotiate issues of authenticity?

MCKUSICK

The idea of the pastoral, of course, goes back to the ancient times. The ancient Greek writers invented the concept of the pastoral landscape, and it’s very related to their form of agriculture, which was pastoral—in other words, they kept sheep, or goats, or cattle on the landscape. The pastoral ideal was invented by urban poets who were nostalgic for this older lifestyle that still existed in remote places. In historically recent times for these poets, this lifestyle had been replaced with more intensive forms of agriculture, the cultivation of crops. Urban life, of course, is not possible unless you’re cultivating a crop like wheat. The pastoral is always inherently nostalgic. It is always looking back to an earlier time where things were better and more peaceful.

Let’s bring it up to the 18th century. William Gilpin invented the concept of the picturesque. He was also a landscape designer, so he, along with a fellow called Capability Brown, invented the idea of the English garden. The English garden was an exercise in nostalgia. It captured a lost pre-history of wild landscape that the lands didn’t currently possess—in other words, all of English land has been cultivated since the Middle Ages, and the only wild lands that now exist are those that have been created by fencing. […] That’s where you get forests in English landscapes.

In the 18th century, the English garden is a reaction against French landscape. The garden at Versailles is a good example of a French landscape, which is geometric in pattern, and intentionally uses very artificial plantings to create a mosaic of color patterns. The English garden is a reaction to that—it uses simple and natural ingredients to fashion a pseudo wild landscape onto the pre-existing agricultural land. A feature you know from Jane Austen is the ha-ha, which is a sunken fence. The sunken fence is meant to be invisible from the perspective of the great house, so you look out upon an unbroken greensward. It prevents sheep from coming all the way up to the door of your house. It creates lawns. I blame the American lawn on the picturesque movement in British landscape architecture. People like William Gilpin and Capability Brown felt that instead of these patterned flower gardens, you should have greensward up to your very door. That, for some reason, has been the most enduring legacy of the picturesque movement in landscape. Even to this day, every American homeowner believes they should have a patch of greensward, even if they’re living in the Arizona desert. They have to have their green patch of grass next to their house, otherwise it’s not a proper home, and they need a white picket fence.

To come to this idea of collecting, collecting is at the very heart of the picturesque ideal. The central concept of picturesque landscape is that it resembles a painting, and it only resembles a painting at certain points of perspective. As you walk through a picturesque landscape, it is intentionally designed to give you prospects—specific places where you can gather a picturesque view. As you progress through the landscape, it’s designed so you go from one picture to the next. It’s like a slideshow. The very act of looking is an act of collecting. You’re creating a picturesque memory for yourself.

There’s a technology called the Claude glass. Claude is a French landscape painter who used a convex mirror to create an image of the landscape, which he would then either directly project upon a piece of paper and trace, almost like a camera obscura, creating a photographically “real” image of the landscape onto a piece of paper; I use the word “real” in quotation marks because it’s not inherently real, it’s just one form of perspective that has been naturalized to us Westerners. Since the Renaissance, we’ve used perspective drawing to create an image of the natural world, so when we do that photographically, it looks real and natural to us, but to folks from non-Western cultures, who don’t have a tradition of landscape painting, a photograph looks weird […] When Native Americans saw profile pictures for the first time, they didn’t accept them. They said, “That’s only half a man.” They only accepted full-face pictures […] The Claude glass was a technology imported from France and used by landscape designers to test the validity of a certain landscape solution. They would stand in front of the landscape, back to it, look at the Claude glass, and because it is a convex mirror, it also emphasizes foreground elements and minimizes background elements. It’s also a darkening mirror; it shades out certain things in the landscape. It is an intentionally intensifying artificial production of landscape, which can then be put on paper and be made into a painting. Even people who were not painters, people whom we would call tourists, would bring their Claude glasses into picturesque places in the late 18th, early 19th century and collect landscapes. They would literally stand with their back to the landscape, looking into their Claude glasses, and say, “Ah! That is picturesque.” In a way, the created landscape, in the mirror or on paper if they could sketch it, was even more real than the thing itself. It mattered more. That was the act of collecting a landscape. We do that today, only we do it with cameras.

INTERVIEWER

It’s like when people go to a concert and watch the entire performance through the screen of their iPhone as they try to record it.

MCKUSICK

Exactly. The whole phenomenon still exists today of snapping landscapes. Usually, there needs to be a figure in the landscape. Tourists are notorious for posing their wives in front of famous monuments and taking a picture. Somehow, that validates the experience. The act of collecting landscapes has certainly existed since the 18th century and already began to be parodied by the early 19th century. There was a whole wonderful set of satirical sketches, or cartoons really, of a character called Dr. Syntax, who would go out into the world and was a bumbling idiot, but still was attempting to collect picturesque landscapes.

The picturesque movement also had a very deep impact on the poetic tradition. There was a whole genre of 18th-century poems called prospect poems—a late example of that is “Tintern Abbey,” which is probably the single most famous prospect poem in literary history. Wordsworth is taking in a prospect a few miles up-river from Tintern Abbey and that’s what the poem is about. The prospect poem, then, lies at the heart of Lyrical Ballads, which is the book that kicked off Romantic poetry for England. The whole notion of the picturesque landscape and the prospect poem really inaugurates the Romantic movement, although the Romantics don’t simply take it over in a naïve way from the 18th century tradition. They sophisticate it, which is good. In its raw form, it’s pretty inauthentic. Wordsworth is already doing something very sophisticated in the prospect form, and Shelley will further internalize it. The “Ode to the West Wind” is a kind of prospect poem that, however, has become deeply psychological to the point where there’s hardly any landscape left to the poem; it’s all an internal landscape. “Mont Blanc” is another example of a prospect poem that presents an entirely internal landscape. Good for Shelley—he took something that was something inauthentic and boring and made it fascinating and complicated and inscrutable.

INTERVIEWER

So, an ecological writer is less authentic if they collect the land.

MCKUSICK

Yes. I think, still, there’s huge amounts of Romantic poetry that derive generically from the prospect poem, but the Romantics have taken that to much deeper psychological depths, demonstrating a much more sophisticated understanding of landscape. My favorite poet in this line is John Clare, who doesn’t do prospect poetry because it is also marked as a bourgeois writing form. John Clare is inhabiting landscapes, so his perspective is not that of a prospect poem, but it is experiential poetry of a dweller in the land. John Clare is a wonderful litmus test to put up against any other poet because John Clare is the most authentic poet in the whole British tradition.

A prospect poem is often stationary, where it goes in a series of slides, whereas in John Clare, it’s a dynamic landscape. You’re walking through it, you’re experiencing it, it’s washing over you, and its inhabitants are talking to you or you’re seeing it through their eyes. You can put a John Clare poem up against any other Romantic poem as a test of authenticity, and some will test out fine and some will not. I’m sorry to say another favorite poet of mine, William Wordsworth, often comes across as seeming inauthentic when you put him up against John Clare because he certainly does have a bourgeois point of view. It’s not that of a dweller, it’s that of a tourist, strolling through the landscape, pausing to take in a prospect, and having a deep mental reaction to that. Wordsworth is profound, but still perhaps less authentic in terms of his relationship to the land, than someone like Clare who was working with the land. […] Wordsworth was reading Gilpin, who writes about the English Lake District. There’s a very direct pipeline of ideas from the picturesque into the Lake District poets; Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Southey were direct inheritors of the picturesque ideal, but they do new things with it.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have any advice for graduate students in the field of Romanticism? What are some things that you wish you knew/were glad that you knew when you were in graduate school or approaching the job market?

MCKUSICK

I have tons of advice, but I want to address this, in part, from the view of ecological criticism. I guess my most fundamental advice to graduate students is to expose yourselves to all different types of literary criticism. No single method is correct or viable or valid on its own, and that certainly applies to ecological literary studies as well as any other “ism”. The last thing you want to do as a graduate student is to say, “Oh, I’m open to all ideas, and I have none of my own.” A grad student does need to stake out their turf and know what “ism” they’re going to be loyal to and really pursue that. But one still has to be capable of intellectual growth. The thing not to do is to be locked into a narrow or ideological reading of literature that blinds you to other dimensions of a text. Ideally, as a literary critic, we want to understand everything that’s there, including the things that are unspoken in a text. As one of my professors liked to put it, “the white space between stanzas are just as important as the stanzas themselves.” The subliminal thinking that is not overt still needs to be understood.

How do you become broadly learned? Hopefully, in a strong English department, there are going to be lots of ideological factions at work. Get to be friends with everyone and learn what everyone is up to and doing. Find which approach works best for you. Hitch your wagon to a star. No one really told me this when I was in grad school, but it really matters who your faculty mentors are because they’re networked into the profession. You want the most prestigious, the most connected, the most famous person, who is also going to be the most busy and the least likely to give you lots of personal time. Hopefully, you can find a golden mean of someone who is A. famous, but B. also a genuinely good person who will give you tons of time and attention and care and feeding and good criticism. It’s great to have arguments with your mentor! You’ll learn more by arguing with them than just agreeing with everything they say and saying, “Oh thank you, great famous professor.” Argue with them. Disagree with them. Test your mettle by going out on a limb and saying something a little dangerous or difficult. Graduate school is a wonderful time to try on new suits of clothes, especially as you’re doing your coursework or coming up toward a dissertation topic. Try to avoid something that is boring or conventional. Try something that is edgy, that puts you into terrain that you’ve never explored before. Often, through the beauty of interdisciplinary study, you can find terrain that no one has explored through that point of view before. Be a little offbeat. Be a little inventive. The world does not need another reading of “Tintern Abbey” or “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” The world needs to find texts that are less travelled by.

One thing that has changed in literary study in the last twenty years is the world has become flat. It used to be that only students at the most prestigious universities would have access to the best rare book libraries, the unpublished manuscripts. Now, everything is available through the wonders of Google Books or interlibrary loan. You can get virtually anything that has ever been published. Yes, you still need to go to rare book archives to get at the original, unpublished stuff, but you can do amazing things through the miracles of electronic publication and the whole field of Digital Humanities. Digital Humanities allow you to do all kinds of digital textual analysis and discover things that have never been seen before. I’ve done some of that work myself through things like corpus linguistics, where you can do statistical analyses of style. Things that were never possible have suddenly become achievable […] Don’t assume that your professors know these tools. Grad students might have an edge on the new technologies of textual analysis that are only possible through “big data” approaches such as corpus linguistics and stylometrics. The beauty of it is that you can predict things and find out that, yep, that’s real. It’s a brave new world out there, so make a daring prediction and go and do your textual analysis and find out if it’s true. No previous generation of grad students could do that, so you guys are going to own the world!

How Iain Banks Helps Me Teach Romanticism

In the past week, dozens of tributes to Scottish writer Iain Banks, have appeared online— hundreds, if you count the smaller, no less poignant, expressions of grief and thanks via social media. Banks died of cancer on June 9th, two months after releasing a statement to his readers announcing his illness and the devastating news of his short life expectancy. Publishing consistently since the early 80s, he leaves behind a significant body of work, including both general fiction and science fiction under the name Iain M. Banks. Though we were “prepared,” the loss hits his fans hard and sooner than expected. Here is my tribute to this Great writer, one that I feel both unqualified and strongly compelled to write. Banks is certainly not a Romantic writer, so it may seem strange for me to write about him here. I discovered his novels only within the past few years, and I’ve still only read a handful of them. Yet, these works have made a lasting impression on me and, more to the point of this post, on my classroom, often paired with Romantic texts.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein has been analyzed and interpreted in many different contexts, providing endless possible readings and uses. For some students, the possibilities are exciting, but, for others, they are also overwhelming. Frankenstein is one of the most teachable Romantic novels for the college classroom, but it can be difficult to convince students not accustomed to reading nineteenth-century texts (or not used to reading much in general) to have the patience to tread through unfamiliar prose styles in order to appreciate the novel’s worth. I think I can assume that many of us have taught this novel and had this experience at some point. There are many strategies to prepare students for the foreignness of earlier texts, but one that I frequently use is to pair a Romantic novel with a more contemporary novel. Twice, I have taught Frankenstein with Iain Banks’s The Wasp Factory (1984) in my freshman literature and composition classroom, a combination that exposes students to two types of literature: both qualify as Gothic, but we see it from two very different time periods and styles. After a week or so of feeling their way through Frankenstein, keeping characters straight and starting to construct understandings of settings and major themes, students develop a tenuous relationship with the text. Then I introduce them to a character named Frank.

“I represent a crime…” (10).

The Wasp Factory tells the story of this disturbed, sixteen-year-old, first-person narrator and his daily routines as he recounts his experiments and murders (that’s right, murders) on his family’s isolated Scottish land. His father, himself a reclusive mad scientist of sorts, has been seminal in Frank’s unstable (my students use the word “insane”) character. Frank, a god in his domain, spends his time fabricating and performing private rituals involving small animals and insects, creatures whose lives and deaths Frank orchestrates in order to tell the future or reinforce his surveillance and control over his island. The crowning glory of these devises is, of course, the wasp factory, a machine constructed from a giant clock face that holds twelve possible deaths for the wasp Frank releases into it. The death chosen by the wasp holds a wealth of information for our narrator. Frank is a powerless character desperate for power, abandoned by his mother and brother. Sound familiar? Frank, despite his age, has killed three times, and the twist ending blows my students’ minds.

“My dead sentries, those extensions of me which came under my power through the simple but ultimate surrender of death, sensed nothing to harm me or the island” (19).

Following up Frankenstein with The Wasp Factory solidifies students’ understandings of both novels by comparing and contrasting. Both texts are inherently about the construction of monstrosity on different levels, as well as human agency in matters of life and death. The creature and Frank are both considered to be monstrous outsiders for their behavior and appearances, but both have also been “created” by their father figures, practically devoid of any female influence. They are not unlike Victor in this sense, as well. They generate power through manipulation of their limited resources with conventionally inacceptable (again, “insane”), behaviors. All three construct their own forms of justice and morality based on adversity, environment, self-delusion, and a striving for power. The students compare and contrast these elements with little prompting from me as Frank and his world accentuate the choices and characteristics of Victor Frankenstein and his creation, not to mention the common themes of nature, science, motherhood, destruction, revenge, madness, etc.

“The factory said something about fire” (23).

The Wasp Factory is not a Romantic text, and that is what makes it so useful in this context: accessible and entertaining, it acts as a stepping stone between the students’ own interests and experiences and those of the early nineteenth century. Students have told me that The Wasp Factory is “the first book I’ve read that has actually made me think.” Another student became so fascinated with the spatial descriptions of Frank’s island that he went out and found a map of the book online, then did the same for Frankenstein. Banks’s novel is incredibly visual, and students want to visualize other texts just as clearly. They squirm at the more graphic, gruesome parts in the novel, but they can’t stop talking about them. The book complicates their own assumptions regarding characters as likable/unlikable and right/wrong and what those judgments are based on. They find Frank frightening and (again) “insane,” yet develop such an affection for him, one that they find themselves extending to the Creature and even to Victor. Writing about both texts together, they explore the complexity of character motives. They learned that liking a character does not mean that they can trust him, and that brings them even closer to that character.

“The wasp factory is beautiful and deadly and perfect” (154).

The strangeness of Banks’s novel, set in a familiar time and told with accessible and beautiful language, opens up a door to welcome other types of strangeness into the classroom, even a strangeness going back almost 200 years. A monster and his creations are always in good company. Iain Banks, thank you for your monsters and your creations. They will continue to teach us so much, not least to enjoy brilliant and important literature.

Banks, Iain. The Wasp Factory. 25th Anniversary Edition. London: Abacus, 2009.

Digital Humanities: My Introduction 1.3

This post is part of a three-part series charting my introduction to the digital humanities. My entrance largely follows from attending a seminar that meets twice a quarter on Saturday mornings entitled, “Demystifying the Digital Humanities” (#dmdh). Paige Morgan and Sarah Kremen-Hicks organize the seminar and it is sponsored through the University of Washington’s Simpson Center for the Humanities.

As the spring term ends for the 2012-2013 school year, I want to conclude this series of posts with some reflections on introducing the digital humanities into my pedagogical practice.

Digital Humanities or Multimodal Composition Class?

The course I designed in March differs greatly from the class I ended with this week. My assignment was English 111. As the course catalog describes it, 111 teaches the “study and practice of good writing; topics derived from reading and discussing stories, poems, essays, and plays.” While the catalog says nothing about the digital humanities, so long as we accomplished the departmental outcomes, my assumption was that a digital humanities (DH) component would only provide us with new tools for thinking through literature and writing.

It was an innocent assumption.

The main issue was scope. For my theme I chose “precarity,” which Judith Butler describes as that “politically induced condition” wherein select groups of people are especially vulnerable to “injury, violence, and death.”[i] Because there are so many “precarious characters” in Wordsworth and Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads, I used this collection for my primary literary text. In addition to investigating precarity, with the Ballads students could also explore multiple genres and how the re-arrangement of poems alters the reading experience. Third, I wanted to use a digital humanities approach. By a DH approach I mean that I would encourage digital humanities values with regards to writing (e.g. collaboration, affirming failure), using digital tools, and learning transferable skills.

By the second half of the course it was clear that the students were confused about the concept, unhappy with the text, and struggling to understand the purpose of the values, tools, and skills. During the second half of the course, I lost hope for my big collaboration project and I dropped the emphasis on the Ballads, focusing instead on rhetorical analyses of blogs and news sites addressing issues of precarious peoples and working conditions, which was especially timely after the recent tragedy in Bangladesh.

Without the literature component, students began to feel more comfortable with the tools and concept, which led to greater motivation and better papers. On the downside, these students signed up for a literature class, which I basically eliminated. The triad of concept, literature, and method should work. But I found that if all three areas are of equal difficulty you may risk blocking success in any of them.

The “transferable skills” were perhaps the most successful part of the course. It is not the case that my classes didn’t teach transferable skills prior to my digital humanities emphasis. But as Brian Croxall has emphasized, we can teach more of them. As far as the digital humanist is concerned, more “skills” is tantamount to learning how to use more tools, which I translated (perhaps erroneously) as more media. So this term, all of my students built websites and blogs.

From building blogs and websites students learned firsthand how medium shapes what we can write, how “writing” might necessarily include design and management, and rather than give a tutorial on how to build these sites, I showed students how they could use Google to search for help on their own. The transferable skills were twofold: build an online platform to host your work (which alters what you can present and how), and learn where and how to find answers to your building questions (and rather than “good” sources, I stressed more of them). While initially these sites were less than satisfactory, by the end of the class students began to realize the potential and implications of the medium, which prompted several of them to re-build their sites during revision phases, taking more time with the organization of pages, images, background colors, and hyperlinks, and then explaining why these changes were important.

The websites and blogs showed signs of success with regards to “building skills,” but these platforms might belong less to the digital humanities and more to “multimodal scholarship.” As the organizers of the Demystifying the Digital Humanities seminar stressed during the April 14th session, digital humanists use their tools to “produce” scholarship, while multimodal scholarship means using tools to “display and disseminate” traditional research. These differences are a bit blurry for me still, but the blurriness might be accounted for by the fact that some of us are “trickster figures” occupying multiple regions on the plane of digital scholarship, as Alan Liu explains in the most recent PMLA (410).[ii]

But Liu adds greater clarity to these distinctions when he explains how a digital humanities project uses “algorithmic methods to play with texts experimentally, generatively, or ‘deformatively’ to discover alternative ways of meaning” (414). The algorithms may be out of reach for English 111 (and me!), but by using Google Sites, Blogger, and Ngram many students were cracking the digital ice and playing. In other words, these basic multimodal tools might be a useful first step towards transferring to a more involved and complicated DH project.

For such a class to be really successful it will require much more planning. For the fall, I am refining what I have rather than adding more tools to the mix. Until I do some serious text mining of my own, it might be safer to design a “writing with digital media” course. But now that Pandora’s (tool) box is open, I don’t see it closing in the future.

After attending the Demystifying the Digital Humanities seminars and writing these posts, I wonder if my introduction has actually led me to media studies instead. My suspicion is that I will touch both areas, because it is ultimately the task or problem that will determine the approach. However, and I believe Liu also demonstrates this point, the digital humanities as a method might prove to be a problem or task generator. With these tools we will become like Darwin returning from the Galapagos with all those varieties of finches sitting on his desk, asking what all these birds have to do with one another. Perhaps the moral should be: the more materials the bigger the questions.

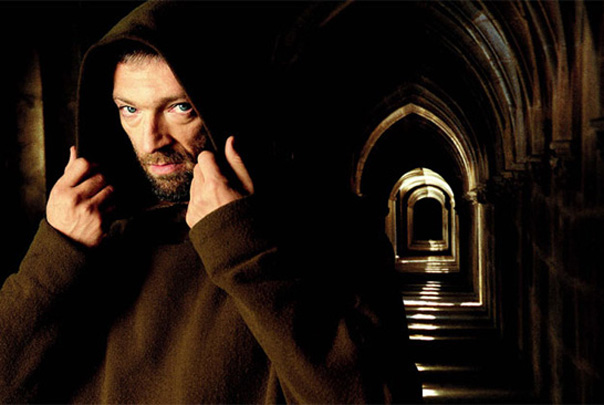

The Monk (Le Moine): A Film Review

As I begin my dissertation chapter on Matthew Lewis, I try to think of not only what research I can contribute to the field but also what related teaching opportunities and activities could be useful in future classes. One possibility for teaching well-known literature is often to include a lesson on adaptation: how can a text change by portraying it through a different medium and all the different lenses that that involves? It helps me to reemphasize to my students the idea that the way a story is formed is a choice made by the author, director, artist, etc. This helps students to see literature as a crafted piece of art that invites multiple interpretations, not just a story that portrays objective, black-and-white facts. Particularly in the case of complex classic literature (or most literature, for that matter), the creator of an adaptation must make drastic sacrifices to reduce a 400-page text to an audience-friendly film under two hours. This is why we have so many different film versions of texts like Frankenstein, Pride and Prejudice, Oliver Twist, etc. (not to mention children’s books). Each one is different.

As I begin my dissertation chapter on Matthew Lewis, I try to think of not only what research I can contribute to the field but also what related teaching opportunities and activities could be useful in future classes. One possibility for teaching well-known literature is often to include a lesson on adaptation: how can a text change by portraying it through a different medium and all the different lenses that that involves? It helps me to reemphasize to my students the idea that the way a story is formed is a choice made by the author, director, artist, etc. This helps students to see literature as a crafted piece of art that invites multiple interpretations, not just a story that portrays objective, black-and-white facts. Particularly in the case of complex classic literature (or most literature, for that matter), the creator of an adaptation must make drastic sacrifices to reduce a 400-page text to an audience-friendly film under two hours. This is why we have so many different film versions of texts like Frankenstein, Pride and Prejudice, Oliver Twist, etc. (not to mention children’s books). Each one is different.

I know of three adaptations of Matthew Lewis’s 1796 novel, The Monk: two versions in English in 1972 and 1990, and the most recent and highly-anticipated French version, Le Moine, released in 2011. Those who have read The Monk would probably not be surprised to learn that all three versions are difficult to find: the novel is complex, with many simultaneous plots that would make a film version seem practically impossible without sacrificing some great material. In terms of the viewing experience of this film, it is a little on the slow side, though the scenery and atmosphere are beautiful and create a believable (if bleak) setting. It is certainly not an action film and involves a lot of contemplative silences and slow discussions. The English subtitles, while understandable, are probably not extremely accurate (or grammatical), placing more weight on the visuals to carry the film. However, while I would not say that Le Moine is a particularly fantastic film—especially with little or no knowledge of the novel—it does do some interesting things that could lead to a pedagogical discussion among higher-level students of what the Gothic does in the late eighteenth century and the way subtle changes in an adaptation help to accentuate those features.

Warning: SPOILERS!

The central storyline of Lewis’s text follows the monk Ambrosio, who, seduced by the demonic Matilda (in disguise), proceeds to seduce the virginal Antonia (his sister), kill her (his) mother and eventually rape and kill her before standing trial at the Inquisition. He is then rescued by the devil, sells his soul, and is dropped off a cliff by Satan. Already, this sounds like it could be a Lord-of-the-Rings-sized trilogy! However, large parts of the novel deviate from this storyline to follow Antonia’s fiancé Don Lorenzo, his sister Agnes, and her lover Don Raymond. Agnes, a nun, has become pregnant by Don Raymond (after a long adventure of his own, involving banditti and the Bleeding Nun) and is imprisoned in the nunnery, where she gives birth and coddles her dead child in one of the most horrific scenes in Gothic literature.

Though it includes a few brief scenes of Agnes’s discovery and punishment and the growing love between Antonia and Don Lorenzo, the film, of course, focuses primarily on the relationship between Ambrosio and Matilda. Matilda, donning a stunningly-unsettling porcelain mask, enters the monastery as a deformed plague victim, who has an uncanny ability to quiet the “voices” in Ambrosio’s head. The devil is already among the citizens of Madrid according to this version, as an exorcism and the warning “It’s here!” foretell Matilda’s identity and Ambrosio’s fated association with her. The multiple layers of deformity, masking, and victimhood suggest an interesting link between illness/ misfortune and theatricality/artifice and (of course) the devil’s involvement in all of it. The exorcisms and the known presence of the devil suggest a more established and ongoing battle with evil that does not appear as strongly as in the novel, though corruption within the church is still present, notably in the Prioress’s dealings with Agnes.

One of the things that I found most interesting in this adaptation, however, is the emphasis on punishment. When Ambrosio turns Agnes over to the Prioress, he tells her that she should want and welcome punishment for her crimes. Yet, Agnes is the only one punished in the film (and she quickly dies of starvation, cursing Ambrosio’s name until the end). Romantic Gothic literature is nothing if not surprisingly conservative: crazy, evil, and scandalous things happen, but the ending is almost always about punishing those involved in some of the cruelest ways possible. In this way, it acts very much like Bakhtin’s idea of the carnivalesque: controlled chaos turns peasants into princes and vice versa, but at the end of the day, order is restored and all goes back to normal.

One of the things that I found most interesting in this adaptation, however, is the emphasis on punishment. When Ambrosio turns Agnes over to the Prioress, he tells her that she should want and welcome punishment for her crimes. Yet, Agnes is the only one punished in the film (and she quickly dies of starvation, cursing Ambrosio’s name until the end). Romantic Gothic literature is nothing if not surprisingly conservative: crazy, evil, and scandalous things happen, but the ending is almost always about punishing those involved in some of the cruelest ways possible. In this way, it acts very much like Bakhtin’s idea of the carnivalesque: controlled chaos turns peasants into princes and vice versa, but at the end of the day, order is restored and all goes back to normal.

In the novel, Agnes survives, but the Prioress who imprisoned her is graphically trampled to death by an angry mob. Ambrosio himself spends weeks in the dungeons of the Inquisition before he finally gives his soul to Matilda in exchange for his freedom. She delivers, but then she (as the devil) also brutally kills him. In the film, however, Ambrosio does end up crawling through the desert after his trial and is confronted by the devil. However, he markedly redeems himself (to some extent): when the devil offers to take him to paradise in exchange for his soul, he asks for the now-insane Antonia’s happiness, instead. He makes a choice to suffer, but that suffering is not imposed upon him, making him into a tragic hero of sorts. A martyr. Lewis’s monstrous and desperate villain of Catholicism has become a creature much more akin to later fiction starting with Shelley’s Frankenstein, in which the monster is not all monster at all… or at least provokes a great deal of pity and admiration.

Despite this, the film is disappointingly conservative in other ways for modeling itself after one of the most shocking novels of all time. Empire magazine says it best in its review of the film when its author says, “An austere, cerebral reading of a book which is unfettered, blood-bolstered and wildly sensationalist — Lewis is the father of torture porn, not a master of subtle chills. It’s interesting and unsettling, with a charismatic lead performance, but nowhere near as shocking as it should be.” The most shocking second half of the novel is condensed into about twenty minutes, taking attention away from Ambrosio’s depravity and giving instead a slow, quiet view of monastic life and one man’s psychological struggle within it.

On the Secondary Source That Changed My Approach to Teaching Keats

In 2002, Charles Rzepka published a paper that brings critical attention to the footnote usually attached to John Keats’s “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer”:

Keats’s mentor Charles Cowden Clarke introduced him to Homer in the robust translation of the Elizabethan poet George Chapman. They read through the night, and Keats walked home at dawn. This sonnet reached Clarke by the ten o’clock mail that same morning. It was Balboa, not Cortez, who caught first sight of the Pacific from the heights of Darien, in Panama, but none of Keats’s contemporaries noticed the error.

Rzepka quotes the Norton Anthology’s 7th edition. I’ve got the 9th handy: it says essentially the same thing. Interestingly, when I taught the poem two weeks ago with reference to Rzepka’s paper, one of my students noted that her 8th edition of Norton mentions that the error is contested. It mentions this in the very footnote that makes the error known. Why did Norton drop this equivocation in the 9th?

In his paper[1] Rzepka hones in on the supposed mistake, Cortez for Balboa, and proceeds to argue thoroughly and convincingly that it matters not whether Keats was mistaken. What matters is whether or not the poet meant to be mistaken, and if so why.

I admire many things about this paper, not least of which is the extreme practicality of its form and subject. It is pragmatic, accessible and applicable not just to the poem, or to Keats’s biography, or for readers, critics, and editors, but for our pedagogies. Rzepka has written a paper for teachers. That is, for us.

Why does it feel so singular to read a rigorous article that takes into account scholarly tradition, literary and cultural history, as well as critical debates, and still speaks for the right now? It’s not that the paper employs some presentism or anachronistic import about proto-neuro-psycho-something-or-other. It doesn’t claim to discuss Truth or Beauty or Nature or Man. No such thing. Rzepka’s paper asks that we entertain the idea that:

“Once we [stop reading “Cortez” as a mistake], we will see that the Darien tableau in which Keats has placed his belated conquistador brilliantly underscores the poignant theme, announced in the very title of his sonnet, of the belatedness of the poet’s own sublime ambitions” (39).

It’s a paper about the idea of interpretation, which offers an interpretation of Keats’s interpretive moves. Rzepka says that grappling with this issue “deserves to be taken seriously by every editor of Keats and every student of the ‘Chapman’s Homer’ sonnet” (38). It’s a paper you can take to class with you. And I will, and did.

As the final class in a week of lectures on Romantic Aesthetics, I taught the sonnet with these questions in mind:

Once your perception of an event or text is reoriented, can you ever see the text without some part of that perceptual shift remaining? Even if you refuse the new information, or even refuse to believe the shift occurred? Is Cortez always a mistake, even if you choose not to think so?

I had the intention of having the class interpret their interpretations, or to re-interpret the usual, received interpretations, of Keats’s sonnet and some of the well-known, often taught Odes. I am sure most of them read “Ode to a Grecian Urn” in high school or first year.

Over the course of the class I gave away biographical hints about Keats and historical clues about the Romantic period, something like this:

How would your perception of “Chapman’s Homer” change if you knew the following:

- Keats’s habits of study at Enfield were “most orderly,” according to Clarke, “[Keats] must have…exhausted the school library, which consisted principally of abridgements of all the voyages and travels of any note” (Rzepka 140).

- Keats owned the book in which Bonnycastle describes Herschel’s original discovery of Uranus (Andrew Motion, Keats, 1997).

- Keats once fought a butcher’s boy for bullying a kitten (Andrew Motion, Keats, 1997).

And this culminated in putting them into groups and passing out excerpts from Keats’s letters. Each group had to read their poem through the excerpt; they had to bring the biographical to bear on the poem in a way that would change the class’ perception of the poem.

It was totally illuminating—such a storm of brains! And the students’ realization that their interpretive power could be used to read the poems charitably or not, seemed to give their efforts that critical self-consciousness that Keats, himself, so utterly possessed.

Romanticism: Periodization and Teaching

A Professor working outside of the period that scholars have come to call Romantic recently said to me, “You identify as a Romanticist? Cool.” Yes, it is indeed cool. The language that he chose to use, however, raised several questions in my mind. Defining Romanticism is a difficult task that has been productively addressed by numerous scholars. For a current and thought provoking definition, here is Michael Ferber’s “Romanticism” from the aptly titled Romanticism: A Very Short Introduction.

“Romanticism was a European cultural movement, or set of kindred movements, which found in a symbolic and internalized romance plot a vehicle for exploring one’s self and its relationship to others and to nature, which privileged the imagination as a faculty higher and more inclusive than reason, which sought solace in or reconciliation with the natural world, which ‘detranscendentalized’ religion by taking God or the divine as inherent in nature or in the soul and replaced theological doctrine with metaphor and feeling, which honored poetry and all the arts as the highest human creations, and which rebelled against the established canons of neoclassical aesthetics and against both aristocratic and bourgeois social and political norms in favor of values more individual, inward, and emotional.”

This definition is indeed a very useful one. I encourage my compatriots to engage with, laud, and/or put pressure on this definition.

For the purpose of this post, I want to examine the two important implications that loom behind defining Romanticism. The debate over what Romanticism means has clear implications for those of us who “identify” as “Romanticists.” In other words, locating the definition of the era/period/movement/ -ism changes what it means when I assert with confidence that I am Romanticist. What is a Romanticist an expert in?

For those pursuing graduate degrees, there is a bizarre bifurcation taking place. In my own work, in conversations with colleagues, and in response to contemporary critics, I often put pressure on Romanticism and the Romantic. When I teach, however, Romanticism is something with clear temporal, aesthetic, and political boundaries. To what extent should our scholarly debates influence the manner in which we teach Romanticism? Do we not participate in the debate when we choose to teach Romanticism in a certain way?

In order to get the conversation started, I have included a few charts that I use to teach Romanticism. Are these images similar to / different from / at odds with the way you have taught Romanticism?

Romanticism Charts

Teaching the Gothic

“We trust… that satiety will banish what good sense should have prevented; and that, wearied with fiends, incomprehensible characters, with shrieks, murders, and subterraneous dungeons, the public will learn, by the multitude of the manufacturers, with how little expense of thought or imagination this species of composition is manufactured.”

“We trust… that satiety will banish what good sense should have prevented; and that, wearied with fiends, incomprehensible characters, with shrieks, murders, and subterraneous dungeons, the public will learn, by the multitude of the manufacturers, with how little expense of thought or imagination this species of composition is manufactured.”

Thus says Samuel Taylor Coleridge in response to Matthew Lewis’s The Monk in 1797, a strange statement from the writer of “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” and “Christabel.”[i] Treated with a certain degree ambivalence by many of the Romantic poets—Wordsworth expressing an outright disdain for “frantic novels, sickly and stupid German Tragedies” in his Preface to Lyrical Ballads—the popularity of the Gothic in the late eighteenth century was difficult to ignore, as was the Gothic nature of the political climate that made most literary and visual descriptions of the French Revolution Gothic almost by default. Indeed, the genre seems to almost anticipate such violent and bloody upheaval, revealing the period’s anxieties about tyrannical rulers and corruption of the aristocracy in its earliest texts. Because of its popularity, bolstered through stage-productions and cheap chap-books, the Gothic’s place within “serious” Romantic literature, it would seem, is itself somewhat meta-Gothic: a position of ambivalence and abjection, of reluctant importance and acknowledgement. It’s almost Twilight-esque status as “pop-lit” of the age (and most subsequent ages) deterred its recognition as a literature of value until surprisingly recently, despite the fact that many Romantic poets—Robinson, Southey, Byron, Shelley, and Keats to name a few… and, yes, even Wordsworth and Coleridge—experimented with the Gothic tradition or at least its features. Clearly, it was something of which even the most established writers could not “weary.” And some, like Mary Wollstonecraft, found ways of shifting Gothic tropes to work for their own purposes, to expose and contextualize the reality of horrors in the here and now:

“Abodes of horror have frequently been described, and castles, filled with spectres and chimeras, conjured up by the magic spell of genius to harrow the soul and absorb the wondering mind. But, formed of such stuff as dreams are made of, what were they to the mansion of despair, in one corner of which Maria sat, endeavoring to recal her scattered thoughts!”[ii]

With these contemporary attitudes toward the Gothic in mind, I recently had the opportunity to give a guest lecture introducing the Gothic to an upper-level undergraduate class on Romantic Literature. They had just finished Frankenstein and were two acts into The Cenci. I will be taking my comps at the end of the semester, examining in the major field of Gothic literature, Romantic to Contemporary, and in the minor field of Romantic Literature. I have, thus, had my head buried in Gothic texts for the past nine weeks, so it was easier said than done to distinguish between what I have been obsessing over and what might actually be useful for students in this survey class.

Some background: Gothic 101

We started with the basics: what does “Gothic” mean? The term Gothic originated from the Goths, the Germanic tribes that brought about the fall of Rome. Its original connotations were barbaric, primitive, uncivilized, and medieval. Yet, around the mid-eighteenth century, a new interest arose in the Goths as conquerors, yes, but the conquerors of Britain. As such, with a rise in nationalism, the British began to see the Goths as the origins of their own civilization and the values upon which it had been built. Thus, the term “Gothic” came to have two meanings associated with the primitive: barbaric but also virtuous.[iii] This second definition is facilitated by a subsequent glorification of the past, antiquity, and medievalism. The perfect example of this is, of course, Horace Walpole, whose behavior even before he pens the Gothic grandfather, The Castle of Otranto, gives insight into the beginnings of the genre. Obsessed with Gothic architecture and antiques, Walpole built Strawberry Hill, a construction which mixed styles, time periods, and materials to cater more to what Walpole considered Gothic than to the restrictions of historical aesthetics. Thus, we have the fragmented mixing of pasts and present that would characterize the literary tradition, emphasizing atmosphere over realism in the interplay between truth and performance. All it needed were a few ghosts. And thus we have the inspiration for the first Gothic novel.

What does that mean?: Making sense of the texts

While it seems obvious that The Cenci would fit into the same Gothic as The Castle of Otranto, it is less clear how Frankenstein can also fall into this classification. We can trace the origins of the Goths, but the definition of what is “Gothic” is still (and probably always will be) contested among scholars, both past and present. My favorite definition and one I see often-cited is Chris Baldick’s: “For the Gothic effect to be attained, a tale should combine a fearful sense of inheritance in time with a claustrophobic sense of enclosure in space, these two dimensions reinforcing one another to produce an impression of sickening descent into disintegration.”[iv]

By then breaking the two texts down according to how they depict time and space, we were then able to touch briefly on other important key terms and aspects. We could begin to see how Victor’s dangerous preoccupation with the ancient forbidden texts of magical science and alchemy might line up with the dangerous power of the Cenci’s ancient and decaying line. We noted the family structures in the two texts, highlighting the absence of the mother and the presence of incest. We compared the structures of the texts themselves, both sprung from the fabrication of manuscripts that frame the narrative itself as old or dangerous. Doubles, the uncanny, paranoia, isolation, excess, the return of the repressed: all could be structured, compared, and contrasted through time and space. I found that keeping it broad and simple, tempting though it was to go into other more dark and dusty corners of this tradition, provided the students with a general framework to apply to their upcoming readings… even those of Wordsworth and Coleridge.

Legitimacy and the Graduate Student

We’ve all heard it: “I don’t feel like I belong here”—the clarion call of English graduate students and the hyper-obsession of meta-conversations within Literature departments at the highest level. What is this obsession, and who really does belong in graduate programs or the academy, if not those who are there already? This problem has been my preoccupation for some time now, so much so that it has crept into my dissertation, in an attempt to unravel the problems of legitimacy, sovereignty, authorship, etc. embedded in Romanticism and Romantic studies.

Trying to tackle these problems as a total framework, or as a problem even at the level of pedagogy, has been met with lots of resistance. My upcoming Fall course on “Banned Books and Novel Ideas” will look at illegitimate textual problems in Ossian’s Tales of Fingal, Byron’s issues with piracy, the thorny controversies in Shakespeare and Defoe, as well as the whole regime of intellectual property surrounding Scott and Coleridge. To inaugurate this course, I began my description with the famous quote from Foucault’s famous essay which he “borrowed” from Beckett: “What matters who’s speaking?” Quite a moment of reflexivity, where Foucault not only questions the regime of authorship, but also uses a phrase that is syntactically tangled and, apparently, illegitimate. I say this because my proposal, after explanation and several revisions, was greeted with disapproval from the legitimizing force of the English department heads; Beckett and Foucault have non-standard English and tangled syntax, it was said—students will be confused and find the course doesn’t have authority! Hmmm…. I have my own responses to this line of argument, but I would be delighted to hear your thoughts on the subject. That is, how does one negotiate teaching texts that are non-standard, taboo, illegitimate etc. while still telling them that plagiarism is naughty-naughty and they must write in standard, syntactically clear English? One easy explanation is making the distinction between discursive and non-discursive texts but, in keeping with truth-telling, even that distinction breaks down with enough interrogation.

Within this same matrix of problems, I have often asked the question of how one can really integrate radical politics into a classroom space? How can one develop a quasi-democratic, anarchic pedagogy when all available models have some basis in logics of sovereignty and authority, delegitimizing certain ways of learning and production of scholarship? Your thoughts are very much appreciated, particularly in relation to your experiences of teaching problematic Romantic texts.