Reading is not one thing but many. Most of all, reading is not passive. “In reality,” writes Michel de Certeau in the opening of The Practice of Everyday Life, “the activity of reading has on the contrary all the characteristics of a silent production.” But what are we producing? And what does the scholarly practice of reading do to this production?

As graduate students we often expect ourselves somehow to swallow texts whole—to get them. We try mightily to read texts simultaneously in terms of their own coherence, elisions, and indeterminacies as textual systems, of their unconscious procedural expression of determinant historical conditions of possibility, of their own stated and unstated relations to their intellectual precursors, and in the light of their reception by scholars or later links in the canonical chain; we strive to keep in mind texts’ political ramifications, how their formal-generic elements engage with other morphologically-related texts, and their relative sympathy or antipathy to various major philosophical concerns or strands of ideological critique; we read texts to find out whether we can instrumentalize our readings for the purposes of conference papers, dissertation chapters, or course syllabi—and maybe to determine whether we like them. More often than not, while reading I am also planning on passing along certain passages to colleagues or photocopying them for friends outside of the academy; wondering whether I could get a pirated PDF instead of waiting the several days for Interlibrary Loan or maybe shelling out the cash for a nice sixties paperback copy of my own, speculating about the biography of the author or the business-end realities of the academic press in question, and so on. Continue reading “Objective Reading”

Dissertating with a Hammer: An Idiot’s Generalizations on Scholarship and Activism

I begin with two passages that will be the epigraphs to my dissertation:

Few critics, I suppose, no matter what their political disposition, have ever been wholly blind to James’s greatest gifts, or even to the grandiose moral intention of these gifts … but by liberal critics James is traditionally put the ultimate question: of what use, of what actual political use, are his gifts and their intention? Granted that James was devoted to an extraordinary moral perceptiveness, granted, too, that moral perceptiveness has something to do with politics and the social life; of what possible practical value in our world of impending disaster can James’s work be? And James’s style, his characters, his subjects, and even his own social origin and the manner of his personal life are adduced to show that his work cannot endure the question.

Hero Worship, Discipleship, and the Romantic Imagination: On Spivak’s Aesthetic Education

“And so I go, asking the students to enter the 200-year-old idiomaticity of their national language in order to learn the change of mind that is involved in really making the canon change. I follow the conviction that I have always had, that we must displace our masters, rather than pretend to ignore them.” So writes Gayatri Spivak at the conclusion of a chapter entitled “The Double Bind Starts to Kick In” in her recent tome An Aesthetic Education in the Age of Globalization. Is Spivak too, I ask, such a master that we must displace if we are to abide by her own conviction? This is a question I want to pursue as I consider her treatment of British romanticism in this mammoth work. Continue reading “Hero Worship, Discipleship, and the Romantic Imagination: On Spivak’s Aesthetic Education”

On His Birthday: Dylan Thomas, Wordsworth, nostalgia and poetry.

Today is the hundredth anniversary of the birth of Dylan Thomas, my first and best love in poetry. Lionized by the culture industry but ignored by the academy, this milestone date will hopefully present an opportunity to reassess the value of Thomas’s work, which I feel is sadly neglected.

It is something of a commonplace for Thomas to be associated with the ‘romantic’ tradition, or to be called a Romantic poet. Continue reading “On His Birthday: Dylan Thomas, Wordsworth, nostalgia and poetry.”

Research Turns Into Artmaking

I recently started a series of prints that began in a flurry of ideas: the wonder of looking close, peeling back the layers, and the intensity of microscopic viewing.

I am trying to dig deeper, revisiting the circular plate and looking at a rich history of images that are inspired by the sphere. Continue reading “Research Turns Into Artmaking”

Laura Moriarty and Geologic Motions

I recently had the pleasure of visiting Art.Science.Gallery – a fresh and inventive place that is nestled in Austin’s Canopy Studios of artists, musicians, galleries and other creative spaces. Hayley Gillespie, Ph.D., the founder of the gallery, is an ecologist and artist with a specialization in endangered salamanders. Though the mission for the gallery is to exhibit art merged with science, Gillespie and her team incorporate events and lectures that help to promote science literacy and increase communication between other scientists, artists, and the public. It’s hard not to be smitten with a gallery that also has a Laboratory for classes – but not a typical art class listing. This summer at Art.Science.Gallery, you can register for Climate Science 101. Continue reading “Laura Moriarty and Geologic Motions”

Experience: I Served in the British Army of 1812

My introduction to the geopolitics of British Romanticism came about in a highly unusual way. In the summer of 2007, I had a job as a historical reenactor: six days a week, I became a foot soldier and musician in a Drum Corps of the British Army during the War of 1812. My one-time service for the honour of the Prince Regent took place at Fort York, a National Historic Site located in downtown Toronto, Canada, and in this post I will share my lived observations of what the daily experiences of colonial military service would have been like for a British soldier at the height of the Romantic period. Continue reading “Experience: I Served in the British Army of 1812”

NGSC E-Roundtable: "Three Ways of Looking at Romantic Anatomy"

Introduction

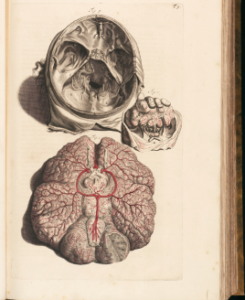

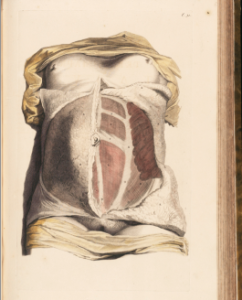

Emily, Laura, and Arden are three graduate students who share interests in Romantic medical science and anatomy. We illustrate our contrasting methods in responding to this article (“Corpses and Copyrights”), which discusses the history of dissection in England through pictures of a medical textbook, William Cowper’s Myotomia reformata, or A New Administration of the Muscles (London, 1724) and legal issues with respect to both bodies and texts as shared properties. The article celebrates the connections between literary and medical fields through its focus on Laurence Sterne’s body-snatched corpse, and the rediscovery of his anatomized skull in the 1960s. In this collaborative post, we each respond to the question: how can our distinctive approach cast new light on such a text? Within the specific field of dissection, we focus on different approaches and questions with respect to the imaginative work of illustration and fiction to depict the body, the power of the body (and its parts) as an object and artifact, and the gendered nature of dissection and the spectacle it created.

Laura Kremmel is a PhD candidate at Lehigh University, specializing in Gothic literature, particularly in the Romantic period, but with teaching interests across all manifestations of the Gothic. Her dissertation considers Gothic literature in the context of medical theory and the Gothic’s imaginative ability to experiment with the limits of those theories and offer literary alternatives. She has also published on zombies and is currently developing an online class on ghosts and technology.

Emily Zarka is a PhD student in Romanticism at Arizona State University focusing on gender and sexuality studies and representations of the undead in the period. She is interested in tracing the literary history of horror monsters from the modern period, and exploring the different ways in which men and women write about and reflect on the undead. Emily has given public talks on why zombies matter, and has an upcoming publication exploring the undead in Wordsworth, Coleridge and Dacre.

Arden Hegele is a PhD candidate at Columbia University, with a dissertation focusing on Romantic medicine and literary method. Her most recent work explores Wordsworth and Keats’s hermeneutic engagement with post-Revolutionary techniques of human dissection, and she will soon be teaching a self-designed course about Frankenstein.

Laura

I love the ideas brought up in this article that conflate the actual bodies on the dissection table and the bodies depicted in the illustrations, and I’m most interested in the aspects of this comparison that get left out in able to make that conflation possible. What immediately strikes me about medical images of the eighteenth century is the sterility of the body and the cleanliness of it, which would not be an accurate depiction of the body on the dissection table: we’re missing all the fluids and the deformity of decay that would have made the body an object of repulsion and abjection. These “ugly” aspects worried Dr. Robert Knox (of Burke and Hare fame), who was disgusted by the interior of the body and thought that seeing it would actually ruin an artist’s sense of beauty (Helen MacDonald writes about this in her book, Human Remains (2006)). In his Great Artists and Great Anatomists (1825), Knox pleads with the artist to always draw a dead arm next to a living arm in order to preserve a division between the dead body as an object of disgust and the beauty of the living. Earlier, in the introduction to his Atlas of Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus,” William Hunter explains that there are two ways to illustrate the cadaver: to draw it exactly as it is shown, thus accurately reproducing one single body, OR to draw it taking into consideration all of the other bodies you have seen, thus producing an informed idealization of the body. Hunter himself claims that he much prefers this second, more imaginative method of depicting anatomy.

Thus, the illustrations take on the ability to fictionalize the body to some extent, prioritizing a style that would serve a pedagogical purpose, if not a realist one. It emphasizes the act of seeing the body, but only seeing the right kind of body. The same is true for preparations made of the body, and John Hunter is famous for making thousands of these: isolated and “prepared” parts of the bodies that would become preserved for the purpose of teaching anatomy (and, indeed, to carry on the idea of the body as property and commodity, unique preparations and parts of the body were a common gift to and from physicians). This is also the way in which fiction plays with ideas of the body, uninhibited by the limits of current medical knowledge. Physicians understood the essential role of the dissected body for understanding anatomy, but physiognomy remained somewhat in the shadows: without opening a living body, it was difficult to grasp how it worked. Thus, they were frustrated by exactly the distinction to which Knox refers. The Gothic is particularly interested in the interior of the body–a large part of which produces fear and shock–and it has an ability to stretch the limits of the body, both living and dead, in ways medicine could not. Writers like Matthew Lewis took the opposite approach to most medical illustrations, embracing the abject body and all its dripping, oozing effects, exploring new ways for the body to function in the process, expanding ideas of vitalism, circulation, and digestion.

Many writers of the Gothic were physicians themselves or close to medical thought, such as Mary Shelley and Lord Byron (close to John Polidori), and dramatist Joanna Baillie (niece of John and William Hunter and brother of Matthew Baillie, who spearheaded an interested in autopsy). The underlying principles of dissection are inherent in many of these works, especially the emphasis on empirical observation of the body in order to understand it. Much critical work has been written about Baillie’s play De Monfort (1798), which ends by displaying two bodies side-by-side (a murderer and his victim) in a type of moral autopsy. The murderer, De Monfort, had been so affected by seeing the corpse of the man he killed that it drove him mad and caused his death. In cases like this, the emphasis on seeing the body, whether on the dissection table, the illustration, or the stage, enters into other areas, such as commercial gain (as the article explains), as well as justice.

Arden

What I find compelling in this article is the emphasis on body-snatching as a way of experiencing a privileged intimacy with a literary legend: here, the act of dissection becomes a physical method for the exegesis of both a literary body and a body of work. As “Corpses and Copyrights” describes, Sterne’s body was taken from his grave and recognized as being the author’s by students in the autopsy theatre. This particular grave-robbery of a literary lion was, apparently, a chance one, prompted by the medical school’s need for demonstrational corpses. As Keats’s hospital training confirms, most corpses for autopsy in the Romantic period were indeed procured by body-snatchers, who were paid off by Sir Astley Cooper and other major surgical instructors. And, since some European medical schools guaranteed their students 500 bodies annually, odds were good that students would eventually identify their “Man in the Pan.”

But, with the disinterred shade of Shakespeare’s Yorick hanging over Sterne’s corpus (“Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him well, Horatio”), we do have to wonder about Sterne’s actual disinterment as serving a more deliberate purpose. As Colin Dickey’s book Cranioklepty (2010) discusses, the purposeful body-snatching of artists was surprisingly prevalent during the Romantic Century. Other artists suffered similar fates to Sterne’s: Haydn, Beethoven, and Mozart’s skulls were reportedly stolen from their graves by admirers (in Mozart’s case, since he was buried in a pauper’s grave, the future thief placed a wire around his neck before burial to help identify him later); in 1817, a malformed skull reported to be Swedenborg’s was offered up for sale in England; Schiller’s skull was mounted by a noble friend in a glass case in a library in 1826; and Sir Thomas Browne’s skull entered the Norwich and Norfolk Hospital Museum in 1848. More familiarly, the physical tokens of the Romantic poets continued to circulate after their deaths: Shelley’s heart was snatched from the funeral pyre and preserved in wine, while (in spite of his request to “let not my body be hacked”), Byron’s autopsy was published, his internal organs were scattered throughout Europe, and his corpse was disinterred in 1938 and lewdly examined in the family crypt. Even now, the Keats-Shelley house at Rome boasts various physical relics of the poets, including locks of their hair.

Why were (and are) Romantic artists’ dissected bodies so fascinating? For me, the anatomizing of Sterne’s skull, which bears marks of abrasions from medical implements, reflects on an important moment in the advances of surgical dissection and autopsy at the end of the eighteenth century, as the parts of the dissected literary body became relics for reanimative reading. Though Sterne’s dissection might be coming out of the anatomy in a satirical tradition (like Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy [1621]), as Helen Deutsch describes in Loving Dr Johnson (2005), at the end of the eighteenth century, the autopsy of a literary giant could bring the reader into an intimate encounter with the truths of his or her body, and even offer a kind of memorializing reanimation. In the case of Johnson, the Preface to the 1784 published account of his postmortem (“Dr Johnson in the Flesh”) described the corpse as “a work of art” that was still “of importance to his friends and acquaintances,” and the postmortem text is positioned as a way for the bereaved Johnsonian to reanimate the body through a deep encounter with its fragmented parts. Boswell’s Life of Johnson (1791) picks up the same language of reanimation through dissection: the directly reported records of Johnson’s speech allow the reader to “see him live,” in contrast to other biographies “in which there is literally no Life.” For Deutsch, this is part of a broader eighteenth-century trend of sentimental dissection: the body of the eponymous heroine in Clarissa (1748), for instance, is “opened and embalmed,” and Lovelace promises to keep her heart, which is stored in spirits, “never out of my sight.” (The real-life corollary of this is perhaps the circuitous journey of Percy Shelley’s heart, the “Cor Cordium” acting as postmortem metonym for the poet’s self). For the Romantics, insight into a fragmented body part seems to have had a reanimating quality for the whole body, and, as I think about it in my dissertation, I find links between medical dissection of human bodies, and practices of excisional close reading of organic literary forms, during the Romantic period.

Emily

Upon examining these illustrations and the accompanying article, I was immediately struck by the gendered implications, namely the differences between male and female dissection and how those acts were illustrated. The article claims that “Usually, the bodies used were those of criminals or heretics – predominantly males in other words. The occasional dissection of a woman, it being a public event, attracted large numbers of spectators by the prospect of the exposure of female organ.” Given the ideas of the time that the female body was somehow more sacred or special because of the presumed virtue of the female sex, it does not seem unsurprising that the male body would be more readily violated after death in such a way. However, the connotations of penetration from the scalpels, forceps, and other tools of dissection seem relevant here especially because they all were wielded by a masculine hand. These sharp blades and other disruptive instruments separated, cut and otherwise maimed flesh in an extremely intimate way. When this was occurring with male corpses, there are of course homoerotic undertones, but what really seems relevant is how this violation of phallic metallic apparatuses was deemed taboo except in rare cases. This might in part explain the public audience that attended female dissections as suggested above. Not only was flesh usually hidden promised to be revealed, but the feminine body was in death capable of being poked and prodded in ways living human males could only dream of. The intimacy of such an act becomes fetish as the public gathers to watch the male scientist push the scalpel further and further into the most intimate areas of a woman’s body.

The framing images displayed in “Corpses and Copyrights” appear to validate the theory that even dead bodies were gendered and sexualized in traditional ways. The first image of the series is the front view of a beautiful, naked woman accompanied by props and scenery reminiscent of Neoclassical art and the Grecian and Roman sources that movement drew its inspiration from (see the Roman copy of Praxiteles’ Venus). The only two places marked on this woman’s body are the breasts (A) and vagina (B), highlighting the parts of her body directly associated with sex and reproduction. We can assume that those areas were meant to be detailed one another page in their segmented, dissected form; when the sex separates from the body and becomes an object of its own. Detaching the female form from the person it belongs to would hardly be considered shocking given the culture of the time. The final image in the illustrative series is another woman (possibly the same one, but with a different artistic arrangement), only this time is is her backside that is drawn and marked. Here the letters adorning her body are more numerous, with areas such as the spine, calves and shoulders given special attention in addition to her bottom. I am fascinated by the artists decision to show only a complete female form, although I am not surprised. To me it suggests not only that the female body, at least in its intact form, is considered more beautiful, but that again the connections between sex and death dominate.

Additionally, the “corpse as commodity” idea challenges the idea of death as escape for men and women alike. For in a culture where women were considered property of men both theoretically and legally, death might be a release from such patriarchal control, albeit in an extremely morbid way. As “Corpses and Copyrights” asserts, “the body was not regarded as property” once dead, and therefore the female could finally be free from her masters, at least in theory. The value given to corpses and prevalence of grave robbing for medical and scientific purposes perverts this supposed freedom by once again giving monetary value to the body, and as the popularity of public female dissections suggests, yet again makes the female form a more rare and valuable object to possess. All of which proves that during the period, nothing could be separated from the politics of patriarchy and gender.

(All images in this post are from Cowper’s Myotomia reformata, and first appeared in “Corpses and Copyrights.”)

The Desert: Spirit of Place and Encountering the Dream

“A work can be as powerful as it can be thought to be. Actual space is intrinsically more powerful and specific than paint on a flat surface. ”

-Donald Judd

My notions about the desert seem a distant and beguiling set of imaginary scenes: as a woman-child of swamp and humid coast, enclosed by longleaf pines and surrounded by ocean on (almost) all sides, the desert seems a fairytale topography created by the mythos of the American West – a gunslinger’s paradise, a no-man’s land, a red-rocked canyon of impenetrable access. Perhaps the desert came before me, but only just slightly. The landscape of familiarity to me was one of green, moist terrain that barely spoke a word of its past except to whisper every now and again in small, chalky rocks of its ancient seas. On occasional walls in bright, sun-drenched rooms hung pictures of faraway places, cacti and high rock walls that I had never imagined. These places surely must be the archaic leftovers of my grandparents’ time – ephemera of nation-building and ranching that only exists in stories. A desert, to my own senses, was a place residing only in the collective past of textbooks and black-and-white television shows. What follows is my report as an investigator of this mythic place.

My current home is in the city of San Antonio. A place nestled geographically and geologically at the center of Texas, riding just under the hill country and atop the Balcones Escarpment, it seems a perfect place to begin an adventure. About one hour in any direction and the topography changes enough to be dramatic. My husband and best friend are my compatriots in this journey, heading west on highway 90. Out in D’Hanis, all the buildings are made of brick and, rightly so. The exterior walls of my apartment and the gallery I used to work in in San Antonio are built with D’Hanis stamped rich red bricks – a testament to the history of kilns originally built in the town I am now driving through. Like vast swaths of sedimentation across a landscape, a source can eventually be located for the small outcrops of clues that bear this interesting feature.

In another few hours we cross the Pecos River, where it has cut so deep down into the lower Cretaceous limestone here that the canyons are concave and bellowing with resilient whites and creams. In some places, the dreary shale gray has stained the limestone over ages, a palimpsest of story upon story. The Pecos itself seems still and chillingly cerulean. To stand and ponder how it could have ever worked at the task of carving stone seems one I can understand logically but still never grasp on a human scale. This canyon took time – time that I can’t fathom in my excitement. It’s not even a very big canyon in the scheme of things geological.

West of the Pecos, the roadcuts get a bit more interesting, as every few miles a new rise has been blasted to make way for the road we travel, and within those slices of high hillside, strata that make up the earth are revealed. Some strata are nice and even, with beautiful separations, and some show great interfingering and mixing up of their constituent parts. It’s a mystery book teasing me from the shelf as I drive past. I want to, in every sense of the word, read it – to find out what happened and in doing so, gain a greater understanding of the land I’m traversing. But we keep pressing on to our destination.

What can the desert offer me? I have a desire to go – to see. The author Rebecca Solnit frequently writes about place and its importance to us spiritually, asthetically, and even within a greater social construct. “The very word desert refers to desertedness, to lack, and the desert is defined by what it is missing,” (Solnit, 65). I think about the times that I have been defined by what I am quite literally “missing,” or what terrible inadequacies I seem to present based solely on patriarchal structures in my life. I can see that the desert is being unfairly compared to ecosystems that it is not and never will be. Much like a desert, a woman has to hold her own in a world defined by male domination, expansion, and desire. In this case, the desert is a place without sufficient water supply to support large human populations, their agriculture, and livestock. The roads and towns are increasingly less populated, with fewer familiar comforts and more trucks. You wouldn’t need a Starbucks to live out here but you would definitely need four-wheel drive. I ponder these ideas as I become acquainted with a place that’s been obscured from me. In the metaphorical tales that I spin while watching wild birds fly up from the roadside brush, I think the desert must be a woman.

Camping in Big Bend Ranch State Park is very remote. We spend about an hour and a half just getting off the main road and driving to the ranger station. There are no paved roads, and our campsite can be located with GPS coordinates. Wind blows around and through you, and you can hear it coming. It rustles the dry brush and sweeps through the openness, warning you of its presence. All you can do out there is knuckle down.

Desert Thoughts:

Is it possible to overuse the term majestic? It seems that every view is deserved of the word, the crest of every hill a new splendor. Something about the setting sun and the large expanse of open space sets the stage for the feeling of true sublimity. Counting posts in the road (one of the only signs of humanness out here) and adding them up to see how far we’ve come, my friend and I decide that, should the Jeep break down, we don’t want to trek 9 miles in the desert sun back to safety. These aren’t city miles near other people, or the possibility of finding gas or shade; these are wide open, scorching miles.

“To be deserted is not to be alone but to be alone with the thought that it could be otherwise,” (Broglio, 34). Reading this essay by Broglio sets the feeling of being alone like a puzzle piece into a greater picture. In the desert I feel small, detached, and even somewhat awestruck, but by being so far away from lots of people, I am open to the possibility that there are other voices to be heard, including my own. “Voice is the attempt to communicate, the desire to be other than abandoned,” (Broglio, 37). Imagine the braying of a wild donkey as it runs past your tent in the middle of the night, its own agenda afoot, with little regard for your temporary dwelling amidst its home. Your heart beats wildly as you wake up, identifying the voice you just heard, listening for danger and finding none. You coo yourself back to sleep with the sound of your own small voice.

I listened to myself in the desert.

***

There is more color here than I every imagined. My previous sketches of “what the desert looks like” might have included raw sienna and burnt umber. Of course I’d imagined the crisp, green cacti, but never did I grasp the varying greens of the scrub in the arroyos, including cottonwoods. Rich purple cacti grow up near small, red and yellow flowering bushes. Rocks of all colors seem to tumble out of the ground, as if their volcanic past is waiting to be told in mafic blacks and greys, punctured by ochre to red iron-stained gravels. Fold in the blue sky upon this picture and the whites of the sunbaked gravels and this is what I saw for two days outside my tent – a place where every color was an inspiration.

***

A fine layer of dust still covers my Jeep after returning from Big Bend a few days later. In the cracks and corners of doors and seams, it collects like silt. Though I washed my hands after breaking camp, every time I touched my jeans or jacket, my fingertips were loaded with the smell of dust again, as though I were still there, my teeth still gritty with sand and my eyes still watering with the irritation of working at survival.

I was hours away from the campsite now, driving east toward home, a clean stretch of lonesome highway in front of me, and my hands were coated anew in rich desert dust. My senses are alive with the smell of something so new and yet so ancient.

Works Consulted:

Broglio, Ron. “Abandonment: Giving Voice In The Desert.” Glossator 7 , 2013. Web. http://glossator.org/2013/03/03/glossator-7-2013-the-mystical-text-black-clouds-course-through-me-unending/

Judd, Donald. “Specific Objects.” Arts Yearbook 8, 1965. [reprinted in Thomas Kellein, Donald Judd: Early Works 1955–1968(exh. cat. New York: D.A.P., 2002)]

Solnit, Rebecca. “Scapeland.” As Eve Said to the Serpent: On Landscape, Gender, and Art. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2001.

Spearing, Darwin. “Roadside Geology of Texas.” Mountain Press Publishing Company. Missoula: 1991.

An Analog Humanities? The Case for Material Technologies

As a scholarly product of my time, I am the first to admit the advantages of the digitization of the humanities: after all, that’s what gives me EEBO and ECCO, transhistorical word searches, our web-based community of fellow Romanticists, and even the ability to edit my dissertation chapter with my old friends, Copy and Paste…

These advantages are not to be scorned lightly, so it is with some trepidation that I pose the following question: what role can an “analog humanities” play in our digital landscape? When, how, and why does the materiality of the literary text give the contemporary scholar a new lens for interpretation? And how can we expand our definition of “technology” to include the technologies that have (silently) accompanied literary studies all along?

I have recently been investigating these questions by going back to the physical foundation of the book—the pre-verbal stage in a text’s life—as a member of the Pine Tree Scholars, a collective sponsored by the Pine Tree Foundation and hosted through Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library. This brand-new organization brings together students with an interest in the material culture of books, and introduces us to an exciting range of book-making practices in the New York City area.

Our first excursion, to the New York Antiquarian Book Fair in April 2013, gave me an incredible glimpse into the world of rare books. The Fair’s many sellers hailed from around the world, and they displayed an almost overwhelming range of manuscripts, printed posters, antique maps, handwritten letters, and, of course, books. In some ways, what impressed me most were not just the first editions—there were some very beautiful Jane Austens—but also the more esoteric, non-paginated artefacts, like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s walking cane and a large and chilling collection of glass eyes. Following the Fair, we had lunch at the Grolier Club, New York’s club for book collectors, which also features a library of rare materials, fascinating exhibits based on members’ personal collections, and a very becoming portrait of the young Walter Scott. For me, this excursion was an unquestioned success: I scored an 1816 five-volume set of The Works of Lord Byron which I then read in preparation for my qualifying exam (probably to the poet’s ghostly dismay).

More recently, the Pine Tree Scholars have delved into more specific practices of book-making, especially where material production crosses into artistry. Last fall, we visited a letterpress studio—Woodside Press, in Brooklyn—which operates letterpresses, wood-block printing, and also a variety of antique print machines, including Linotype and Monotype systems from the late nineteenth century. To my great pleasure, just as we visited, the printers were working on a special commission to print Shelley’s “Ozymandias.” I was also excited to see that the arrangement of letters on the “keyboard” of the 1890s Linotype printing press followed Sherlock Holmes’s account of the most frequently-occurring letters in English, documented famously in “The Adventure of the Dancing Men” (etaoin shrdlu). At Woodside Press, I also learned the crucial difference between a “type” and a “font”: a “type” refers to a “typeface,” or a specific design of the letters of the alphabet, while a “font” is a mass noun that describes the necessary quantity of pieces of type required for printing a book manuscript. Woodside’s metal fonts included many familiar names—Garamond and Palatino, among others—but also a number of unusual typefaces, of which some were of the Press’s own design. And I was astonished to learn that one letterpress expert can distinguish between typefaces just by looking at their punctuation marks!

We next visited Dieu Donné Papermill in midtown Manhattan, where I produced several (very experimental) sheets of handmade paper. Dieu Donné is a workspace for artists, art therapists, and their clients, as well as members of the public interested in learning paper-making techniques. Here, paper-makers create their artworks by processing linen, cotton (including old blue jeans and medical gowns), hemp, wood pulp, abaca (used to make tea bags), or other natural fibers, in a watery solution; the cellulose within the fibrous mixture allows the sheet of paper to fuse together when the pulp is laid on a screen and the water drained or pressed away. I was very interested to learn that the artistic technique we were using—creating sheets of paper individually on screens—was still the dominant commercial way of making paper from cotton and rag fibers during the early Romantic period; the first continuous paper-making machine was invented in France in 1799 and introduced to England in 1803 and the United States in 1817, replacing the earlier practice of making sheets by hand. Now to determine whether my Works of Lord Byron is printed on handmade sheets…

My latest foray into the material practices of book-making was a bookbinding session: the artist and bookbinder Susan Mills visited the Columbia Library and instructed us in the practices of sewing together the bindings of books. To me, this was an especially remarkable experience, since I was quickly and easily able to produce my own 96-page chapbook using extremely simple tools—in addition to sheets of paper, I needed only a paper-knife, an awl, a needle and thread, and a scrap of linen. During the Romantic period, book-binding would have been done by hand, by (usually) anonymous craftspeople, whose contributions are often only recorded in tiny holes in the pages near the book’s spine (where tiny drops of blood, from pricked fingers, decayed the paper more quickly). And readers would normally have cut the pages by hand; I note, with admiration for an anonymous previous reader, that my Byron‘s pages are cut perfectly cleanly. (Later addendum: they were probably “guillotined” by the printer.)

As I return to the question about the value of the “analog” humanities—that is, a deliberate return to the material technologies used in the production of literary texts—I think that experiencing the physical processes of making books, as I have been so lucky to do, can offer a unique and valuable pedagogy for the contemporary Romanticist. Having seen printing presses, paper-making, and book-binding in action, I have such an affective appreciation for the meticulous craftsmanship of my little 1816 Works of Lord Byron. The volumes’ ink is still vivid, the pages don’t crumble, and the tightly sewn bindings remain unbroken. The many type settings, ranging from the bold Gothic lettering of the title of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage to the tiny typefaces, italicized passages, and Greek fonts in the glosses, testify to a material investment in the text that extends beyond the poet. From my “analog” adventures, I’ve learned that such small details as printing errors—like the notorious misprint in Austen’s Persuasion that “Lady Russell loved the mall”—are not just criteria for editorial footnotes; they are also reminders of the book-making process and the unseen but tremendous effort of Romantic-era craftspeople to support, in material fashion, what they saw as literary inspiration worth recording.

(All photos—and the textual materials depicted therein—belong to Arden Hegele)