My husband got a new job as a software developer, and right now he’s working from home. I have found in the short time since he took this new position that we cannot both work from home at the same time. The work environment he cultivates to be productive does not jive with my own. I like to work from my couch, preferably with a dog or two sleeping next to me. I like to have the television on but muted, and the front windows open to let in natural light. My husband works in the adjacent room, our office, with two computer screens in front of him, listening to the comedy station on Pandora and holding videoconferences with his development team intermittently throughout the day. My threshold for how many stand up routines I can endure is severely low, I must admit. So in the last month, I have been transitioning to an on-campus work routine. Continue reading “Rethinking Workspace”

Guest Post: Songs of Urban Innocence and Experience

By Katherine Magyarody

I was recently chatting to a friend about the NASSR Graduate Student Caucus and the suggestion that posts could include original poetry. It is an exciting prospect, but also vexing. What might contemporary poetry on a Romanticist blog look like? If someone wrote something similar in tone to Keats’s early faux-Spenserian verse would anyone find value in it? Did it have to be an Ode? Was there anything in our proximity as remote and beautiful as the Lake District? Looking around, I nearly concluded that the world is too much with us. Continue reading “Guest Post: Songs of Urban Innocence and Experience”

Laura Moriarty and Geologic Motions

I recently had the pleasure of visiting Art.Science.Gallery – a fresh and inventive place that is nestled in Austin’s Canopy Studios of artists, musicians, galleries and other creative spaces. Hayley Gillespie, Ph.D., the founder of the gallery, is an ecologist and artist with a specialization in endangered salamanders. Though the mission for the gallery is to exhibit art merged with science, Gillespie and her team incorporate events and lectures that help to promote science literacy and increase communication between other scientists, artists, and the public. It’s hard not to be smitten with a gallery that also has a Laboratory for classes – but not a typical art class listing. This summer at Art.Science.Gallery, you can register for Climate Science 101. Continue reading “Laura Moriarty and Geologic Motions”

NGSC E-Roundtable: "Three Ways of Looking at Romantic Anatomy"

Introduction

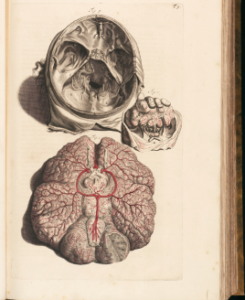

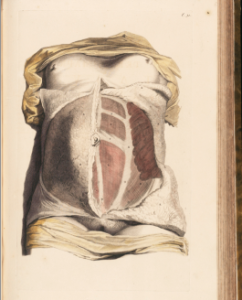

Emily, Laura, and Arden are three graduate students who share interests in Romantic medical science and anatomy. We illustrate our contrasting methods in responding to this article (“Corpses and Copyrights”), which discusses the history of dissection in England through pictures of a medical textbook, William Cowper’s Myotomia reformata, or A New Administration of the Muscles (London, 1724) and legal issues with respect to both bodies and texts as shared properties. The article celebrates the connections between literary and medical fields through its focus on Laurence Sterne’s body-snatched corpse, and the rediscovery of his anatomized skull in the 1960s. In this collaborative post, we each respond to the question: how can our distinctive approach cast new light on such a text? Within the specific field of dissection, we focus on different approaches and questions with respect to the imaginative work of illustration and fiction to depict the body, the power of the body (and its parts) as an object and artifact, and the gendered nature of dissection and the spectacle it created.

Laura Kremmel is a PhD candidate at Lehigh University, specializing in Gothic literature, particularly in the Romantic period, but with teaching interests across all manifestations of the Gothic. Her dissertation considers Gothic literature in the context of medical theory and the Gothic’s imaginative ability to experiment with the limits of those theories and offer literary alternatives. She has also published on zombies and is currently developing an online class on ghosts and technology.

Emily Zarka is a PhD student in Romanticism at Arizona State University focusing on gender and sexuality studies and representations of the undead in the period. She is interested in tracing the literary history of horror monsters from the modern period, and exploring the different ways in which men and women write about and reflect on the undead. Emily has given public talks on why zombies matter, and has an upcoming publication exploring the undead in Wordsworth, Coleridge and Dacre.

Arden Hegele is a PhD candidate at Columbia University, with a dissertation focusing on Romantic medicine and literary method. Her most recent work explores Wordsworth and Keats’s hermeneutic engagement with post-Revolutionary techniques of human dissection, and she will soon be teaching a self-designed course about Frankenstein.

Laura

I love the ideas brought up in this article that conflate the actual bodies on the dissection table and the bodies depicted in the illustrations, and I’m most interested in the aspects of this comparison that get left out in able to make that conflation possible. What immediately strikes me about medical images of the eighteenth century is the sterility of the body and the cleanliness of it, which would not be an accurate depiction of the body on the dissection table: we’re missing all the fluids and the deformity of decay that would have made the body an object of repulsion and abjection. These “ugly” aspects worried Dr. Robert Knox (of Burke and Hare fame), who was disgusted by the interior of the body and thought that seeing it would actually ruin an artist’s sense of beauty (Helen MacDonald writes about this in her book, Human Remains (2006)). In his Great Artists and Great Anatomists (1825), Knox pleads with the artist to always draw a dead arm next to a living arm in order to preserve a division between the dead body as an object of disgust and the beauty of the living. Earlier, in the introduction to his Atlas of Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus,” William Hunter explains that there are two ways to illustrate the cadaver: to draw it exactly as it is shown, thus accurately reproducing one single body, OR to draw it taking into consideration all of the other bodies you have seen, thus producing an informed idealization of the body. Hunter himself claims that he much prefers this second, more imaginative method of depicting anatomy.

Thus, the illustrations take on the ability to fictionalize the body to some extent, prioritizing a style that would serve a pedagogical purpose, if not a realist one. It emphasizes the act of seeing the body, but only seeing the right kind of body. The same is true for preparations made of the body, and John Hunter is famous for making thousands of these: isolated and “prepared” parts of the bodies that would become preserved for the purpose of teaching anatomy (and, indeed, to carry on the idea of the body as property and commodity, unique preparations and parts of the body were a common gift to and from physicians). This is also the way in which fiction plays with ideas of the body, uninhibited by the limits of current medical knowledge. Physicians understood the essential role of the dissected body for understanding anatomy, but physiognomy remained somewhat in the shadows: without opening a living body, it was difficult to grasp how it worked. Thus, they were frustrated by exactly the distinction to which Knox refers. The Gothic is particularly interested in the interior of the body–a large part of which produces fear and shock–and it has an ability to stretch the limits of the body, both living and dead, in ways medicine could not. Writers like Matthew Lewis took the opposite approach to most medical illustrations, embracing the abject body and all its dripping, oozing effects, exploring new ways for the body to function in the process, expanding ideas of vitalism, circulation, and digestion.

Many writers of the Gothic were physicians themselves or close to medical thought, such as Mary Shelley and Lord Byron (close to John Polidori), and dramatist Joanna Baillie (niece of John and William Hunter and brother of Matthew Baillie, who spearheaded an interested in autopsy). The underlying principles of dissection are inherent in many of these works, especially the emphasis on empirical observation of the body in order to understand it. Much critical work has been written about Baillie’s play De Monfort (1798), which ends by displaying two bodies side-by-side (a murderer and his victim) in a type of moral autopsy. The murderer, De Monfort, had been so affected by seeing the corpse of the man he killed that it drove him mad and caused his death. In cases like this, the emphasis on seeing the body, whether on the dissection table, the illustration, or the stage, enters into other areas, such as commercial gain (as the article explains), as well as justice.

Arden

What I find compelling in this article is the emphasis on body-snatching as a way of experiencing a privileged intimacy with a literary legend: here, the act of dissection becomes a physical method for the exegesis of both a literary body and a body of work. As “Corpses and Copyrights” describes, Sterne’s body was taken from his grave and recognized as being the author’s by students in the autopsy theatre. This particular grave-robbery of a literary lion was, apparently, a chance one, prompted by the medical school’s need for demonstrational corpses. As Keats’s hospital training confirms, most corpses for autopsy in the Romantic period were indeed procured by body-snatchers, who were paid off by Sir Astley Cooper and other major surgical instructors. And, since some European medical schools guaranteed their students 500 bodies annually, odds were good that students would eventually identify their “Man in the Pan.”

But, with the disinterred shade of Shakespeare’s Yorick hanging over Sterne’s corpus (“Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him well, Horatio”), we do have to wonder about Sterne’s actual disinterment as serving a more deliberate purpose. As Colin Dickey’s book Cranioklepty (2010) discusses, the purposeful body-snatching of artists was surprisingly prevalent during the Romantic Century. Other artists suffered similar fates to Sterne’s: Haydn, Beethoven, and Mozart’s skulls were reportedly stolen from their graves by admirers (in Mozart’s case, since he was buried in a pauper’s grave, the future thief placed a wire around his neck before burial to help identify him later); in 1817, a malformed skull reported to be Swedenborg’s was offered up for sale in England; Schiller’s skull was mounted by a noble friend in a glass case in a library in 1826; and Sir Thomas Browne’s skull entered the Norwich and Norfolk Hospital Museum in 1848. More familiarly, the physical tokens of the Romantic poets continued to circulate after their deaths: Shelley’s heart was snatched from the funeral pyre and preserved in wine, while (in spite of his request to “let not my body be hacked”), Byron’s autopsy was published, his internal organs were scattered throughout Europe, and his corpse was disinterred in 1938 and lewdly examined in the family crypt. Even now, the Keats-Shelley house at Rome boasts various physical relics of the poets, including locks of their hair.

Why were (and are) Romantic artists’ dissected bodies so fascinating? For me, the anatomizing of Sterne’s skull, which bears marks of abrasions from medical implements, reflects on an important moment in the advances of surgical dissection and autopsy at the end of the eighteenth century, as the parts of the dissected literary body became relics for reanimative reading. Though Sterne’s dissection might be coming out of the anatomy in a satirical tradition (like Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy [1621]), as Helen Deutsch describes in Loving Dr Johnson (2005), at the end of the eighteenth century, the autopsy of a literary giant could bring the reader into an intimate encounter with the truths of his or her body, and even offer a kind of memorializing reanimation. In the case of Johnson, the Preface to the 1784 published account of his postmortem (“Dr Johnson in the Flesh”) described the corpse as “a work of art” that was still “of importance to his friends and acquaintances,” and the postmortem text is positioned as a way for the bereaved Johnsonian to reanimate the body through a deep encounter with its fragmented parts. Boswell’s Life of Johnson (1791) picks up the same language of reanimation through dissection: the directly reported records of Johnson’s speech allow the reader to “see him live,” in contrast to other biographies “in which there is literally no Life.” For Deutsch, this is part of a broader eighteenth-century trend of sentimental dissection: the body of the eponymous heroine in Clarissa (1748), for instance, is “opened and embalmed,” and Lovelace promises to keep her heart, which is stored in spirits, “never out of my sight.” (The real-life corollary of this is perhaps the circuitous journey of Percy Shelley’s heart, the “Cor Cordium” acting as postmortem metonym for the poet’s self). For the Romantics, insight into a fragmented body part seems to have had a reanimating quality for the whole body, and, as I think about it in my dissertation, I find links between medical dissection of human bodies, and practices of excisional close reading of organic literary forms, during the Romantic period.

Emily

Upon examining these illustrations and the accompanying article, I was immediately struck by the gendered implications, namely the differences between male and female dissection and how those acts were illustrated. The article claims that “Usually, the bodies used were those of criminals or heretics – predominantly males in other words. The occasional dissection of a woman, it being a public event, attracted large numbers of spectators by the prospect of the exposure of female organ.” Given the ideas of the time that the female body was somehow more sacred or special because of the presumed virtue of the female sex, it does not seem unsurprising that the male body would be more readily violated after death in such a way. However, the connotations of penetration from the scalpels, forceps, and other tools of dissection seem relevant here especially because they all were wielded by a masculine hand. These sharp blades and other disruptive instruments separated, cut and otherwise maimed flesh in an extremely intimate way. When this was occurring with male corpses, there are of course homoerotic undertones, but what really seems relevant is how this violation of phallic metallic apparatuses was deemed taboo except in rare cases. This might in part explain the public audience that attended female dissections as suggested above. Not only was flesh usually hidden promised to be revealed, but the feminine body was in death capable of being poked and prodded in ways living human males could only dream of. The intimacy of such an act becomes fetish as the public gathers to watch the male scientist push the scalpel further and further into the most intimate areas of a woman’s body.

The framing images displayed in “Corpses and Copyrights” appear to validate the theory that even dead bodies were gendered and sexualized in traditional ways. The first image of the series is the front view of a beautiful, naked woman accompanied by props and scenery reminiscent of Neoclassical art and the Grecian and Roman sources that movement drew its inspiration from (see the Roman copy of Praxiteles’ Venus). The only two places marked on this woman’s body are the breasts (A) and vagina (B), highlighting the parts of her body directly associated with sex and reproduction. We can assume that those areas were meant to be detailed one another page in their segmented, dissected form; when the sex separates from the body and becomes an object of its own. Detaching the female form from the person it belongs to would hardly be considered shocking given the culture of the time. The final image in the illustrative series is another woman (possibly the same one, but with a different artistic arrangement), only this time is is her backside that is drawn and marked. Here the letters adorning her body are more numerous, with areas such as the spine, calves and shoulders given special attention in addition to her bottom. I am fascinated by the artists decision to show only a complete female form, although I am not surprised. To me it suggests not only that the female body, at least in its intact form, is considered more beautiful, but that again the connections between sex and death dominate.

Additionally, the “corpse as commodity” idea challenges the idea of death as escape for men and women alike. For in a culture where women were considered property of men both theoretically and legally, death might be a release from such patriarchal control, albeit in an extremely morbid way. As “Corpses and Copyrights” asserts, “the body was not regarded as property” once dead, and therefore the female could finally be free from her masters, at least in theory. The value given to corpses and prevalence of grave robbing for medical and scientific purposes perverts this supposed freedom by once again giving monetary value to the body, and as the popularity of public female dissections suggests, yet again makes the female form a more rare and valuable object to possess. All of which proves that during the period, nothing could be separated from the politics of patriarchy and gender.

(All images in this post are from Cowper’s Myotomia reformata, and first appeared in “Corpses and Copyrights.”)

The Desert: Spirit of Place and Encountering the Dream

“A work can be as powerful as it can be thought to be. Actual space is intrinsically more powerful and specific than paint on a flat surface. ”

-Donald Judd

My notions about the desert seem a distant and beguiling set of imaginary scenes: as a woman-child of swamp and humid coast, enclosed by longleaf pines and surrounded by ocean on (almost) all sides, the desert seems a fairytale topography created by the mythos of the American West – a gunslinger’s paradise, a no-man’s land, a red-rocked canyon of impenetrable access. Perhaps the desert came before me, but only just slightly. The landscape of familiarity to me was one of green, moist terrain that barely spoke a word of its past except to whisper every now and again in small, chalky rocks of its ancient seas. On occasional walls in bright, sun-drenched rooms hung pictures of faraway places, cacti and high rock walls that I had never imagined. These places surely must be the archaic leftovers of my grandparents’ time – ephemera of nation-building and ranching that only exists in stories. A desert, to my own senses, was a place residing only in the collective past of textbooks and black-and-white television shows. What follows is my report as an investigator of this mythic place.

My current home is in the city of San Antonio. A place nestled geographically and geologically at the center of Texas, riding just under the hill country and atop the Balcones Escarpment, it seems a perfect place to begin an adventure. About one hour in any direction and the topography changes enough to be dramatic. My husband and best friend are my compatriots in this journey, heading west on highway 90. Out in D’Hanis, all the buildings are made of brick and, rightly so. The exterior walls of my apartment and the gallery I used to work in in San Antonio are built with D’Hanis stamped rich red bricks – a testament to the history of kilns originally built in the town I am now driving through. Like vast swaths of sedimentation across a landscape, a source can eventually be located for the small outcrops of clues that bear this interesting feature.

In another few hours we cross the Pecos River, where it has cut so deep down into the lower Cretaceous limestone here that the canyons are concave and bellowing with resilient whites and creams. In some places, the dreary shale gray has stained the limestone over ages, a palimpsest of story upon story. The Pecos itself seems still and chillingly cerulean. To stand and ponder how it could have ever worked at the task of carving stone seems one I can understand logically but still never grasp on a human scale. This canyon took time – time that I can’t fathom in my excitement. It’s not even a very big canyon in the scheme of things geological.

West of the Pecos, the roadcuts get a bit more interesting, as every few miles a new rise has been blasted to make way for the road we travel, and within those slices of high hillside, strata that make up the earth are revealed. Some strata are nice and even, with beautiful separations, and some show great interfingering and mixing up of their constituent parts. It’s a mystery book teasing me from the shelf as I drive past. I want to, in every sense of the word, read it – to find out what happened and in doing so, gain a greater understanding of the land I’m traversing. But we keep pressing on to our destination.

What can the desert offer me? I have a desire to go – to see. The author Rebecca Solnit frequently writes about place and its importance to us spiritually, asthetically, and even within a greater social construct. “The very word desert refers to desertedness, to lack, and the desert is defined by what it is missing,” (Solnit, 65). I think about the times that I have been defined by what I am quite literally “missing,” or what terrible inadequacies I seem to present based solely on patriarchal structures in my life. I can see that the desert is being unfairly compared to ecosystems that it is not and never will be. Much like a desert, a woman has to hold her own in a world defined by male domination, expansion, and desire. In this case, the desert is a place without sufficient water supply to support large human populations, their agriculture, and livestock. The roads and towns are increasingly less populated, with fewer familiar comforts and more trucks. You wouldn’t need a Starbucks to live out here but you would definitely need four-wheel drive. I ponder these ideas as I become acquainted with a place that’s been obscured from me. In the metaphorical tales that I spin while watching wild birds fly up from the roadside brush, I think the desert must be a woman.

Camping in Big Bend Ranch State Park is very remote. We spend about an hour and a half just getting off the main road and driving to the ranger station. There are no paved roads, and our campsite can be located with GPS coordinates. Wind blows around and through you, and you can hear it coming. It rustles the dry brush and sweeps through the openness, warning you of its presence. All you can do out there is knuckle down.

Desert Thoughts:

Is it possible to overuse the term majestic? It seems that every view is deserved of the word, the crest of every hill a new splendor. Something about the setting sun and the large expanse of open space sets the stage for the feeling of true sublimity. Counting posts in the road (one of the only signs of humanness out here) and adding them up to see how far we’ve come, my friend and I decide that, should the Jeep break down, we don’t want to trek 9 miles in the desert sun back to safety. These aren’t city miles near other people, or the possibility of finding gas or shade; these are wide open, scorching miles.

“To be deserted is not to be alone but to be alone with the thought that it could be otherwise,” (Broglio, 34). Reading this essay by Broglio sets the feeling of being alone like a puzzle piece into a greater picture. In the desert I feel small, detached, and even somewhat awestruck, but by being so far away from lots of people, I am open to the possibility that there are other voices to be heard, including my own. “Voice is the attempt to communicate, the desire to be other than abandoned,” (Broglio, 37). Imagine the braying of a wild donkey as it runs past your tent in the middle of the night, its own agenda afoot, with little regard for your temporary dwelling amidst its home. Your heart beats wildly as you wake up, identifying the voice you just heard, listening for danger and finding none. You coo yourself back to sleep with the sound of your own small voice.

I listened to myself in the desert.

***

There is more color here than I every imagined. My previous sketches of “what the desert looks like” might have included raw sienna and burnt umber. Of course I’d imagined the crisp, green cacti, but never did I grasp the varying greens of the scrub in the arroyos, including cottonwoods. Rich purple cacti grow up near small, red and yellow flowering bushes. Rocks of all colors seem to tumble out of the ground, as if their volcanic past is waiting to be told in mafic blacks and greys, punctured by ochre to red iron-stained gravels. Fold in the blue sky upon this picture and the whites of the sunbaked gravels and this is what I saw for two days outside my tent – a place where every color was an inspiration.

***

A fine layer of dust still covers my Jeep after returning from Big Bend a few days later. In the cracks and corners of doors and seams, it collects like silt. Though I washed my hands after breaking camp, every time I touched my jeans or jacket, my fingertips were loaded with the smell of dust again, as though I were still there, my teeth still gritty with sand and my eyes still watering with the irritation of working at survival.

I was hours away from the campsite now, driving east toward home, a clean stretch of lonesome highway in front of me, and my hands were coated anew in rich desert dust. My senses are alive with the smell of something so new and yet so ancient.

Works Consulted:

Broglio, Ron. “Abandonment: Giving Voice In The Desert.” Glossator 7 , 2013. Web. http://glossator.org/2013/03/03/glossator-7-2013-the-mystical-text-black-clouds-course-through-me-unending/

Judd, Donald. “Specific Objects.” Arts Yearbook 8, 1965. [reprinted in Thomas Kellein, Donald Judd: Early Works 1955–1968(exh. cat. New York: D.A.P., 2002)]

Solnit, Rebecca. “Scapeland.” As Eve Said to the Serpent: On Landscape, Gender, and Art. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2001.

Spearing, Darwin. “Roadside Geology of Texas.” Mountain Press Publishing Company. Missoula: 1991.

Quarterly Editor's Note: To Spring

“Turn thine angel eyes upon our western isle

which in full choir hails thy approach, O Spring”

-William Blake, “To Spring”

How true Blake’s words ring for this Chicagoan continuing to warm following the coldest winter on record. And so I write to wish all involved in the romantic studies blog(e)sphere a very collegial start to spring! Unsurprisingly, over the last few months, NGSC authors have continued to produce innovative work at a highly energetic pace. In what follows–and in my final such post of the year–I look back at some of what I found to be among the more incisive thoughts and ideas disseminated on the NGSC blog from January through April. NGSC authors wrote on topics of critical importance to a range of our constituents across the humanities (and beyond), covering such subjects as collaborative modes of engagement, the process building a trajectory of thought and insight between one’s undergraduate training and studies at the graduate level, to the place of economics and literature. We also published advice from established scholars in the field on preparing for comprehensive exams. The winter writing season was an important one for the NGSC.

The start to the year saw the publication of the blog’s first collaborative post, composed by Arden Hegele, artist in (e-)residence Nicole Geary, and myself on Romanticism and Geology. The piece took the form of a free flowing conversation, and ended up centering on how the material forms and discourses surrounding geology become factors of both romantic literary and contemporary art production. This allowed connections between nineteenth- and twentieth-century art and literature to become visible for us, particularly as creative investments in geology inform shared concerns with respect to art and politics. At an especially illuminating juncture in the dialogue, Arden acted as interlocutor for Nicole with the question of how she sees “geologically-inspired works of art,” including Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, as “engaging with the materiality of literary texts.” Nicole, in her response, connected geological form with the materials of textual production, observing that its “remarkable when you come upon stacked strata in the field and see rocks lined up like books on a shelf.” Importantly–and this accounts for one reason I find Nicole’s work as a sculptor and printmaker so fascinating–Nicole draws our attention so effectively to the way in which the earth itself comprises a geological field of signification to be made legible. Yet, like any text, it resists complete interpretation, offering breaches, lacunas, and other absences of meaning. “Volumes go missing,” Nicole reminds us. Excitingly, the series will be continued in May with a piece on the close reading of anatomical texts by Arden, NGSC Co-Chair, long time blog contributor, and Gothic studies specialist Laura Kremmel, as well as the ASU19C Colloquium member and specialist on romantic ideas of the undead Emily Zarka. So, look out for that.

Likewise, on the collaborative side of things, newly minted Ph.D. Candidate Kaitlin Gowan (also of the extraordinarily enterprising ASU19C contingent) wrote a fabulous and timely post on life after exams. There Kaitlin shares how she overcame the challenges of composing her dissertation prospectus. In doing so she made the vital point that, when faced with a daunting writing exercise, we so often do best to proceed by working ideas out out loud, with our colleagues. If, as Kaitlin reminds, our work depends on the passion we bring to it, and our colleagues prove crucial to reminding us of the enthusiastic group of scholars we’re part of as romanticists, the simple act of talking becomes a matter of tantamount importance for success in arriving at the point of being ABD.

In yet another innovative and inspiring post on the methods of literary analysis, Deven Parker’s January piece looked at Media Archaeology. There Deven nicely highlights processes of intellectual expansion in precisely the sort of seminar (in her case, “Media Archaeology” led by Lori Emerson) one might think at first unrelated to one’s earlier period-based work. Deven takes a point of departure from media archaeology’s imperative that we “expose structures of power embedded within the hardware of modern technology, revealing the ways in which media exert control over communication and provide the limits of what can be said and thought.” The result Deven extrapolates is an impetus to consider “texts from the inside out.” In turn, we are to question what books “tell us about the cultural conditions and constraints imposed by the media in which they were (and are) written, manufactured, and consumed.” It seems to me that the move to consider contemporary modes of production, and the theoretical modes of discourse they generate, so frequently proves critical for thinking about one’s own scholarship, even if it is primarily concerned with earlier periods. In addition, I would very much like to hear more from those of you reading the blog on what modes of contemporary media you enjoy thinking about, and the theoretical frameworks you utilize to do so.

Equal in brilliance for its bringing of the interdisciplinary to the fore of the blog, Renee Harris in a March post on “Use Value and Literary Work” zeroed in on how interests in romanticism and economics prove mutually illuminating. In a show of how the milestones in a graduate program lead one to the ideas that sustain important long-term work, Renee shared her justifications for her chosen comprehensive exam lists. At a key point, Renee contends that “The writers we study desire a lasting cultural influence. They seek to shape and correct, to play a significant role in cultural formation and the national story. I argue that this desire to influence and make a mark is a symptom of economic insecurity.” Indeed, it would seem that we need to understand to a much larger extent than we do the way in which such a bourgeois condition of pragmaticism informs the conditions of production with which we are concerned in the nineteenth century. I can’t wait to see how Renee will light the way to precisely this important frame of reference.

Last, on a similar front, blogger and interviewer extraordinaire Jennifer Leeds compiled words of wisdom from five scholars in our field on preparing for comprehensive exams. Perhaps the best of which comes from the medical humanities scholar Brandy Schillace, currently at Case Western University. Dr. Schillace made the salient point, which she was led to by her studies in theology, that “disciples ‘not worry’ about what they would say in advance. When the time came to speak, they would.” While I can only admit to my own experience in this regard, too often I feel as though I attempt to plan everything I say in advance, particularly with regard to my qualifying exams. This usually leads to unnecessary anxiety and less than fulfilling results. Hence, I find Dr. Schillace’s rejoinder a great one. We spend a good deal of time with ideas. Why wouldn’t we be heartened to know, and be confident that when we need them, the ideas will be there.

And with that I can sincerely say I look forward to another quarter of writing on the blog!

An Analog Humanities? The Case for Material Technologies

As a scholarly product of my time, I am the first to admit the advantages of the digitization of the humanities: after all, that’s what gives me EEBO and ECCO, transhistorical word searches, our web-based community of fellow Romanticists, and even the ability to edit my dissertation chapter with my old friends, Copy and Paste…

These advantages are not to be scorned lightly, so it is with some trepidation that I pose the following question: what role can an “analog humanities” play in our digital landscape? When, how, and why does the materiality of the literary text give the contemporary scholar a new lens for interpretation? And how can we expand our definition of “technology” to include the technologies that have (silently) accompanied literary studies all along?

I have recently been investigating these questions by going back to the physical foundation of the book—the pre-verbal stage in a text’s life—as a member of the Pine Tree Scholars, a collective sponsored by the Pine Tree Foundation and hosted through Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library. This brand-new organization brings together students with an interest in the material culture of books, and introduces us to an exciting range of book-making practices in the New York City area.

Our first excursion, to the New York Antiquarian Book Fair in April 2013, gave me an incredible glimpse into the world of rare books. The Fair’s many sellers hailed from around the world, and they displayed an almost overwhelming range of manuscripts, printed posters, antique maps, handwritten letters, and, of course, books. In some ways, what impressed me most were not just the first editions—there were some very beautiful Jane Austens—but also the more esoteric, non-paginated artefacts, like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s walking cane and a large and chilling collection of glass eyes. Following the Fair, we had lunch at the Grolier Club, New York’s club for book collectors, which also features a library of rare materials, fascinating exhibits based on members’ personal collections, and a very becoming portrait of the young Walter Scott. For me, this excursion was an unquestioned success: I scored an 1816 five-volume set of The Works of Lord Byron which I then read in preparation for my qualifying exam (probably to the poet’s ghostly dismay).

More recently, the Pine Tree Scholars have delved into more specific practices of book-making, especially where material production crosses into artistry. Last fall, we visited a letterpress studio—Woodside Press, in Brooklyn—which operates letterpresses, wood-block printing, and also a variety of antique print machines, including Linotype and Monotype systems from the late nineteenth century. To my great pleasure, just as we visited, the printers were working on a special commission to print Shelley’s “Ozymandias.” I was also excited to see that the arrangement of letters on the “keyboard” of the 1890s Linotype printing press followed Sherlock Holmes’s account of the most frequently-occurring letters in English, documented famously in “The Adventure of the Dancing Men” (etaoin shrdlu). At Woodside Press, I also learned the crucial difference between a “type” and a “font”: a “type” refers to a “typeface,” or a specific design of the letters of the alphabet, while a “font” is a mass noun that describes the necessary quantity of pieces of type required for printing a book manuscript. Woodside’s metal fonts included many familiar names—Garamond and Palatino, among others—but also a number of unusual typefaces, of which some were of the Press’s own design. And I was astonished to learn that one letterpress expert can distinguish between typefaces just by looking at their punctuation marks!

We next visited Dieu Donné Papermill in midtown Manhattan, where I produced several (very experimental) sheets of handmade paper. Dieu Donné is a workspace for artists, art therapists, and their clients, as well as members of the public interested in learning paper-making techniques. Here, paper-makers create their artworks by processing linen, cotton (including old blue jeans and medical gowns), hemp, wood pulp, abaca (used to make tea bags), or other natural fibers, in a watery solution; the cellulose within the fibrous mixture allows the sheet of paper to fuse together when the pulp is laid on a screen and the water drained or pressed away. I was very interested to learn that the artistic technique we were using—creating sheets of paper individually on screens—was still the dominant commercial way of making paper from cotton and rag fibers during the early Romantic period; the first continuous paper-making machine was invented in France in 1799 and introduced to England in 1803 and the United States in 1817, replacing the earlier practice of making sheets by hand. Now to determine whether my Works of Lord Byron is printed on handmade sheets…

My latest foray into the material practices of book-making was a bookbinding session: the artist and bookbinder Susan Mills visited the Columbia Library and instructed us in the practices of sewing together the bindings of books. To me, this was an especially remarkable experience, since I was quickly and easily able to produce my own 96-page chapbook using extremely simple tools—in addition to sheets of paper, I needed only a paper-knife, an awl, a needle and thread, and a scrap of linen. During the Romantic period, book-binding would have been done by hand, by (usually) anonymous craftspeople, whose contributions are often only recorded in tiny holes in the pages near the book’s spine (where tiny drops of blood, from pricked fingers, decayed the paper more quickly). And readers would normally have cut the pages by hand; I note, with admiration for an anonymous previous reader, that my Byron‘s pages are cut perfectly cleanly. (Later addendum: they were probably “guillotined” by the printer.)

As I return to the question about the value of the “analog” humanities—that is, a deliberate return to the material technologies used in the production of literary texts—I think that experiencing the physical processes of making books, as I have been so lucky to do, can offer a unique and valuable pedagogy for the contemporary Romanticist. Having seen printing presses, paper-making, and book-binding in action, I have such an affective appreciation for the meticulous craftsmanship of my little 1816 Works of Lord Byron. The volumes’ ink is still vivid, the pages don’t crumble, and the tightly sewn bindings remain unbroken. The many type settings, ranging from the bold Gothic lettering of the title of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage to the tiny typefaces, italicized passages, and Greek fonts in the glosses, testify to a material investment in the text that extends beyond the poet. From my “analog” adventures, I’ve learned that such small details as printing errors—like the notorious misprint in Austen’s Persuasion that “Lady Russell loved the mall”—are not just criteria for editorial footnotes; they are also reminders of the book-making process and the unseen but tremendous effort of Romantic-era craftspeople to support, in material fashion, what they saw as literary inspiration worth recording.

(All photos—and the textual materials depicted therein—belong to Arden Hegele)

NGSC E-Roundtable: Romanticism & Geology

Introduction: This piece comprises the first of a series of interdisciplinary dialogues that will appear quarterly on the NGSC Blog. The initial iteration finds NGSC contributing writers Arden Hegele, Jacob Leveton, and artist in residence Nicole Geary engaging with geology as a factor in the production both of Romantic poetry and contemporary sculpture. Towards this end, they collectively looked at a range of geologically oriented literary texts (Felicia Hemans’s “The Rock of Cader Idris,” Charlotte Smith’s “Beachy Head,” and Percy Shelley’s “Mont Blanc”), works by the visual artists Robert Smithson and Blane de St. Croix, and literary, art-historical, and ecological criticism. Arden, Jacob, and Nicole then posed a series of questions for, and responded to, one another in a discussion that pivots upon a set of shared aesthetic problems and conceptual issues linking current critical and contemporary creative practices.

Roundtable:

Arden: On the subject of the nonhuman voice in Nature, in “Mont Blanc,” Shelley writes that the mountain’s “voice” is “not understood / By all, but which the wise, and great, and good / Interpret, or make felt, or deeply feel” (80-83). How do you see Shelley’s mountain’s form in relation to poetic form, or, how might you relate the challenge of geological interpretation to the interpretation of Romantic literature?

Jacob: This is a great question with which to lead off, and I think provides an effective frame to derive some important points regarding the relation between Shelley’s poetry and politics. Of course, the lines to which you’ve directed my attention drive toward some of the liberatory aspects of Shelley’s poetic project at the time. The poet addresses Mont Blanc and posits that,“Thou hast a voice, great mountain, to repeal / Large codes of fraud and woe; not understood by all, but which the wise, and great, and good / interpret, or make felt, or deeply feel” (80-83). The lines advance the point that Mont Blanc as a nonhuman geological form retains a voice to speak. That voice is comprehended by the “wise, and great, and good” who experience the mountain’s affective force at a high level of intensity (to “deeply feel”). Such a knowing-subject, indeed the Shelleyan poet, interprets the mountain’s geological form and communicates it in a way that effectively manifests itself as a field of social-critical potentiality. What I mean by this is that the poetic engagement with Mont Blanc, that itself generates the poem’s form, is geared to be mobilized in challenging and overturning social inequities. The poetic form that Shelley’s “Mont Blanc” makes available is one that takes geological interpretation as a point of departure for the purpose of social critique, and so relates to broader issues regarding interpretations of Romantic literature informed by historical-materialist theoretical investments, and the field of poetry and politics, more generally.

Nicole: Jacob, “Mont Blanc” seems to be written with a lonely and inhuman aura, one that puts nature out of the grasp of humankind. Do you agree that, as Heringman writes, it helped “mobilize the analogy between geological and political revolution” (13-14)?

Jacob: Your question is a wonderful one, as well–and, actually, while I’d agree that “Mont Blanc” is written with a profoundly inhuman aura I’m convinced it’s one that encodes a form of revelry in the nonhuman other. Ever since my first time working with that particular text, I’ve found it to offer a particularly energetic intellectual jouissance in its impellation that the reader recognize a significant interconnectivity with the natural environment. In this regard, the natural environment can be seen as deeply other and simultaneously co-constitutive of a self that is connected with all other sentient and non-sentient beings. This is why I found Heringman’s remarks so persuasive, with respect to how the “Romantic recognition of the earth’s unpredictability and difference from human interests” ultimately “permits progressive analogies to human agency” (13). One valuable concept the movement to posthumanism gives us (though one which the field of late eighteenth-century cultural production makes possible, by way of writers like Rousseau, Joseph Ritson, Erasmus Darwin, and others) is that the world in which we find ourselves is comprised of a rich myriad of human and nonhuman life and that to understand what it is to be human it is at once necessary to understand what it is to be human in relation to nonhuman life, the natural environment, and non-sentient matter. Geologically, it is the non-sentience of the mountainscape that Shelley’s poem engages with the utmost force, and its that difference between the human poet and nonhuman natural/geological phenomena that drives the poem. This is what I believe that poet is getting at when crafting the image of “The everlasting universe of things” which “Flows through the mind, and rolls its rapid waves” (1-2). The poetic metaphor is taken from the Arve as the river that cuts through the ravine where the poet is positioned, with geological processes here comprising the primary factor of Shelley’s poetic production. Nonhuman geological and human subjectivities are differentiated, yet come together within the poem’s form as a zone of human/nonhuman environmental contact. They’re connected as Shelley’s poem draws out a vector of signification that links the Arve as an example of a formative geological agent that continually carves the mountainscape, the poet’s consciousness in writing, and the reader’s subjectivity in reading. These notions advance Heringman’s argument quite well. If geological formations like Mont Blanc make visible the way in which the earth is in a continual state of transformation–and it’s a given that species do best when they are adaptable to change and humans constitute one species position within a broader web of nonhuman life–then it follows that a commitment to progressive thought and engagement proves integral to the absorption of geology in Shelley’s poem.

Nicole: What I really fell for in “Beachy Head” was the long stretch of meandering we did through what felt like a mix of memory and storytelling. It’s as though we are briefly on the ground at this place, then suddenly no longer conforming to space and time. I find that it’s deceptive at first. Can you talk about how you find the form of this poem lends itself to the underlying story?

Arden: “Beachy Head” is such a rich poem, generically as well as geologically. Although it’s clearly working in the Romantic tradition in its description of sublime natural landscapes, it also looks back to an older genre — the loco-descriptive poem — which characterized eighteenth-century works like James Thomson’s The Seasons (1726-1730). In the loco-descriptive poem, the speaker’s point of view moves fluidly between spaces through the act of looking, and the poem describes the different landscapes in view; importantly (and in contrast with most Romantic poetry), the energy carrying the poem isn’t so much the developing emotional charge, but rather the speaker’s changing observational position within a landscape. This active eye prompting topographical transitions is much of what we get in Smith’s 1807 poem, especially in lines like these: “let us turn / To where a more attractive study courts / The wanderer of the hills” (447-49). Here, Smith signals how her speaker’s eye carries “us” between geographical sites and their relation to her memories.

But, as you suggest, Nicole, Smith’s work is compelling because the landscapes in question prompt temporary flights away from the locations that she describes — including Beachy Head itself — as the speaker contemplates their relation to her emotional state. These jumps away from the landscape into recollected emotion is what feels most Romantic about the poem. For example, Smith’s denunciation of happiness is one of the work’s most poignant moments: “Ah! who is happy? Happiness! a word / That like false fire, from marsh effluvia born” (258-59). To me, this is an intriguing moment for the poem’s physical environment, since the simile associates happiness with a paranormal feature (a will-o’-the-wisp), in contrast to the many concrete landscapes of the poem — Beachy Head itself, the stone quarry, the cottages, the cave in the rock, and so on. But the ignis fatuus also helps to reveal the poem’s ongoing mechanism for the speaker’s nostalgic leaps: here and elsewhere, the ground gives direct rise to the emotions that the speaker experiences. (As a side note, “false fire, from marsh effluvia born” also invokes the miasmatic theory of disease popular during the period, which maintained that toxic gases would arise from the ground and spread contagion – a rather chilling way of describing “happiness”).

The historical and biographical contexts of “Beachy Head” are also quite interesting with respect to the poem’s treatment of time and space, especially in a scientific context. While writing was a source of necessary income for Smith (she was the only earner for her ten children), she took pleasure and relief in scientific practices like botany, and it seems to me that her somewhat loco-descriptive survey of the landscape of Beachy Head alludes to her personal practices of dispassionate scientific observation. An early reviewer of the posthumous poem remarked that

“It appears also as if the wounded feelings of Charlotte Smith had found relief and consolation […] in the accurate observation not only of the beautiful effect produced by the endless diversity of natural objects[,] but also in a careful study of their scientific arrangement, and their more minute variations.” (Monthly Review, 1807)

In keeping with what this reviewer notices, one of the poem’s main projects seems to be to classify different types of rock — the “chalk […] sepulchre” of the cliffs (723), the “stupendous summit” of Beachy Head itself (1), the “castellated mansion” (514), the “stone quarries” (471), and even the sedimented sea-shells, fossils, and “enormous bones” beneath the sea (422). But the poem also moves beyond classification by relating natural forms to poetic lyricism: for example, Smith describes “one ancient tree, whose wreathed roots / Form’d a rude couch,” where “love-songs and scatter’d rhymes” were “sometimes found” (581-84). At the poem’s conclusion, the rock of Beachy Head itself inspires verse, as “these mournful lines, memorials of his sufferings” are “Chisel’d within” (738-39); indeed, Smith’s own lines appear to have emerged from the physical rock. Moreover, supporting its thematic transitions between spaces and even outside of time, “Beachy Head” isn’t confined to a single verse form — the two sets of inset songs (in variable quintains and sestets) break up the sedimented quality we get with the long passages of blank verse. So the meandering quality that you notice between the poem’s specific geographies and abstract memories also applies to the fluctuating relationship between the verse forms, between the various locations and historical moments the poem describes, and, perhaps most importantly, between the relationship of scientific and poetic practices, which Smith ultimately tries to reconcile.

Jacob: Arden, I was particularly struck by the wonderful resonance between your suggestion that we read Charlotte Smith’s “Beachy Head” and Nicole’s decision that we look at Blane de St. Croix’s Broken Landscape III (Fig. 1), since both works utilize geology as a means to think through the concept of national boundaries. In what ways might the ideas you find in Broken Landscape III intersect Smith’s poem? Just as well, how might de St. Croix’s strategies as a visual artist diverge from those of Smith as a poet?

Arden: I’m so glad that you drew my attention to the political similarities between Charlotte Smith and Blane de St. Croix’s works. Both artworks are connected in their different ways to the question of politically-charged national borders. Smith’s perspective can certainly cast new light on de St. Croix’s contemporary art, and I see at least two ways in which the pieces can work together in productive dialogue. First, their portrayals of their respective borders share certain formal similarities, in spite of the very different natures of the artworks. Second, the works diverge in the mechanisms by which they represent the borders as liminal spaces: while de St. Croix is invested in showing how the deep strata of the Mexico-US border’s geological formation acts as a barrier between the nations, Smith finds that the France-England border’s geology reveals similarity underlying the nations’ apparently radical differences.

Both artists engage with the idea of sedimentation as a formal tool for political commentary. In “Beachy Head,” Smith regularly draws the reader’s attention to Beachy Head’s distinctive white cliffs, the tallest in Britain, whose layers of chalk point to a long-standing geological history of increasing division from the opposite coast by means of marine erosion over millennia. For Smith, the continual geological breakdown between the two nations, through this process of erosion, is a provocative metaphor for their political relationship. In its allusions to the Norman Conquest, the battle of Beachy Head of 1690 (which the English lost), and the tensions between the nations during the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, the “scroll voluminous” of “Beachy Head” offers a versified representation of this erosion (122). Presented in chronological order, each incident of conflict with France gives way to the next until the reader reaches sea-level and England’s triumph: “But let not modern Gallia form from hence / Presumptuous hopes” against England, the “Imperial mistress of the obedient sea” (146-47, 154). In the political ramifications of its eroding structure, “Beachy Head” has much in common with Broken Landscape III, which is also interested in the sedimentation of a politically-charged international border. For de St. Croix, however, the formalism of sediment is not figured through erosion, but rather through accretion. Discourses about the border have, over time, accumulated in layers, just as layers of rock have accreted in the border’s geological history. De St. Croix’s representation of the border as a human-scale sedimented wall explores how its underlying discourses have built up to create an insurmountable barrier in the present (unlike the real border, de St. Croix’s installation actually prevents the viewer’s ability to walk across it).

At the same time, though, the two works differ considerably in the function of their sedimentation. As Lily Gurton-Wachter argues, Smith resists the idea that France and England were “natural enemies” (a term used pejoratively to describe their strained relationship at the turn of the nineteenth century), and instead finds a common ground for them in their shared geological past. The poet contemplates whether the bottom of the sea, cast up in cliff form at Beachy Head, serves as the area of continuity between the nations: “Does Nature then / Mimic, in wanton mood, fantastic shapes / Of bivalves, and inwreathed volutes, that cling / To the dark sea-rock of the wat’ry world?” (383-86). While at one point Smith calls Romantic geology “but conjecture” (398), the general implication of the poem is that geology can help to locate a literal, deep-seated common ground between the opposed nations. De St. Croix, on the other hand, finds only political difference in the geology underlying the border. The human imposition of international boundaries on the surface of the earth is so metaphysically weighty that it actually carries downwards physically into its subterranean strata, in spite of the fact that each nation’s side is effectively the same in material and appearance.

Arden: Nicole, I’m interested in your thoughts on the materiality of landscape as a source for art. In Robert Smithson’s film about “Spiral Jetty,” the artist says that “the earth’s history seems at times like a story recorded in a book, each page of which is torn into small pieces. Many of the pages and some of the pieces of each page are missing.” How do you see geologically-inspired works of art — especially an “entropic” project like Smithson’s, or Blane de St Croix’s meticulous topography — engaging with the materiality of literary texts? And, how does your study of Romanticism help you to understand this material relationship?

Nicole: It’s especially remarkable when you come upon stacked strata in the field and see rocks lined up like books on a shelf. This metaphor instantaneously becomes ingrained within you as you run your finger down the stack, looking for the book (rock) you want to pull out. In the history of the earth, pages, sometimes whole volumes go missing. We suffer those convulsions and catastrophes, and the earth rebuilds itself from the pieces. Spiral Jetty is made from rocks, water, mud, evaporites, and time (Fig. 2).

But not just that, it is a place. Spiral Jetty is difficult to reach, sometimes not able to be seen due to changes in the level of the Great Salt Lake. In reading romantic-period texts, I’m reminded of the overwhelming sense of the sublime that artists felt for certain places. Certain topographies, either remote or only able to be accessed by memory (as so wonderfully illustrated in “Beachy Head”) hold a history that engages and sometimes mystifies. So, too, does the Broken Landscape series by de St. Croix as it not only shows the surface, or present tense, but it digs into the depths of what came before our tense border anxieties. Broken Landscape III looks directly at ontological constructs upon the landscape that never existed before human-made activity, but doesn’t negate the rock record.

What I find fascinating is that this rock record is always around us, ever complex yet at our disposal to read. There is some comfort in the idea that we can make sense of the word, quite literally, by translating it like an ancient tome. I think that through Romanticism, I’m actually able to understand more about the emotional weight I give to rocks themselves. By reading through the Scottish Enlightenment and the geological revolution, I understood that what I was going through artistically was my own new science: a way of naming and identifying my emotions without feeling them – calling them the Other.

Jacob: This year, I’ve become increasingly influenced by Rebecca Beddell’s The Anatomy of Nature: Geology and American Landscape Painting, 1825-1865 in terms of the way in which, as Beddell explains, the division of labor between artists and scientists is essentially a discursive construction. Namely, here, I’m interested in how reading Bedell’s art-historical analysis might relate to, or gave you a space to imagine, your own work, perhaps in a different way than you had prior. In this regard, I’m drawn especially to the preface to her book, where Bedell suggests that in the nineteenth-century: “American landscape painters and geologists then stood on common ground. We now tend to consign art and science to different epistemologies, regarding them as distinctive pursuits, with completely different methodologies, directed towards completely different ends” while in the nineteenth-century art and science proved an interconnected spectrum of pursuits “in both popular perception and practice” (xi). What I’m wondering is how you consider about your own work within this trajectory. I’m thinking mainly of your 2011 Secondary Sediment series of prints that I think so powerfully evokes the relation between personal memory and geological space, and especially the play of text and image in “IX” (Fig. 3).

Nicole: Jacob, this is such a great question, because I specifically thought about this, too, when I was reading Beddell’s introduction. It seems a social construct based on educational or vocational pursuits has rendered art and science separate pursuits in our recent history, but the idea of a more common acquisition of knowledge and shared respect for these fields was in vogue during the age of Manifest Destiny. A different resurgence in this kind of thinking is afoot, with places like Science Gallery (https://dublin.sciencegallery.com/), the resurrection of LACMA Art + Technology Lab (http://lacma.org/Lab), and the CERN Artist’s Residency (http://arts.web.cern.ch/collide), to name only a few art and science collaborations.

To answer your question, my work does straddle both realms. It’s a mix of personal memoir related to the land it was experienced in. I find that the economic aspects of landscape cannot be separated from their role as passive backdrop to this “American dream” sedative. To deal with one part of the land or the space I live in requires me to seriously investigate all parts – it’s an element of knowing the land that I think a poem like “Beachy Head” deals with in a wonderful way.

The idea that we should mine the earth for its riches, or fight wars for those resources, the same principles that as a youth I could feel patriotic about, are now the ideas that I question in my work. What is worth exploiting (property, resources, and lives) and at what cost for the betterment of humankind? Who can really own land? In “A Place on the Glacial Till,” Thomas Fairchild Sherman writes a personal, historical, and geological history. A story of the animals and plants of his native Oberlin, Ohio, he writes of a place that is clearly familiar and dear to him when he says that: “Our homes are but tents on the landscape of time, and we but visitors to a world whose age exceeds our own 100 million times. We own only what the spirit creates.”

At what cost does the land stop becoming land? I think Solnit shares a fine example of this in her essay (see “Elements of a New Landscape,” 57). The work “El Cerrito Solo” by Lewis deSoto was initiated by a friend’s remark that it was “too bad the mountain wasn’t there anymore.” Essentially, a small hill had been sourced for it’s material until it was no longer there – a story that’s full of what I think of as the ripping out of a page from one of the volumes in the rock record of the earth. Almost painfully, the artist says, “you could be in the landscape while driving on the freeway.” This reminds me of living in South Dakota and driving on pink-hued roads, colored this way because of the quarrying of local Sioux quartzite, the words of this story echoing in my thoughts. How many “little mountains” disappeared from the landscape to make these roads? At the intersection of art and geology, I read of a similar story that took place in Belize of the unfortunate destruction of a 2,000+ year-old Mayan temple, locally named Noh Mul, or Big Hill. A local contractor was quarrying the site for its limestone to create roadfill, but now embedded archaeological artifacts are totally lost and broken cultural relics have become part of the landscape. Ultimately, the “otherness” of Nature is no longer a separate entity conceptually at bay but is a real, interactive part of our lives. I believe art can help us transform the way we think about landscape and its effect on us.

(Link: http://hyperallergic.com/71065/ancient-mayan-temple-destroyed-in-belize/)

(Link: http://edition.channel5belize.com/archives/85391)

I think the time is right to invest in people. One of the biggest problems that I see with contemporary Western culture (as this is what I can speak to), is a lack of focus on local histories and real science, and an art world that seems fixated on the cult of celebrity, or too quickly moves on from one fad to another. I think the reason I became a printmaker was that somewhere at the core of my being, I enjoy the slow work and old-fashioned ethos of making something from an antiquated technology. It’s possible that I set myself up to be interested in history specifically because of that, but a lot of the work I drift toward or care about is art about the sciences and questioning the role of the author, or the authoritative voice. By this I mean searching for authentic stories of people so that they not be forgotten by history due to their gender, race, or sexuality. I look for things to have meaning and depth beyond their surface. Rocks and big outcrops, with their stony gazes, seem to have a lifetime of stories to tell, even if their faces are unyielding. I have to agree with Shelley on this point, where he ascribes a voice to Mont Blanc–in the lines to which Arden first drew our attention. What I read in this passage is the work of the artist and the geologist. To make the voice of the mountain known, through study and familiarity, through knowledge and wisdom, and to transmit that feeling through the power of metaphor, and of unity with the landscape. Who can say which job belongs to whom?

Works Consulted:

Poetry

Felicia Hemans, “The Rock of Cader Idris” (1822)

Percy Shelley, “Mont Blanc” (1817)

Charlotte Smith, “Beachy Head” (1807)

Art

Blane de St Croix, “Broken Landscape III” (2013)

Robert Smithson, “Spiral Jetty” (1970)

Criticism

Bedell, Rebecca. The Anatomy of Nature: Geology and American Landscape Painting, 1825-1875. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

Gurton-Wachter, Lily. “’An Enemy, I suppose, that Nature has made’: Charlotte Smith and the natural enemy.” European Romantic Review 20, 2 (2009): 197-205.

Heringman, Noah. Romantic Rocks, Aesthetic Geology. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004.

Solnit, Rebecca. “Elements of a New Landscape.” As Eve Said to the Serpent: On Landscape, Gender, and Art. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2001.

What I Learned About Truth in Pursuit of Reality

In response to Deven’s post regarding her journey toward archaeology via the pursuit of reality, I wanted to use the resonance I felt in her story as a jumping off point for my own post about the nature of reality. While I am compelled by approaches to understanding defined by logic and reason, I find myself sometimes working against both in my role as an artist. I make work in a system that allows for the full creation of possibility and ideas – a world that ascribes to sets and grouping but also readily casts them off in order to make great leaps and bounds of the imagination. Contemporary artists, unfettered by traditional labels that have served much of western art history (though still enriched by that history), move about from media to media, always seeking the best solution to visual questions. Art of the mind is valued as well as art of the hand, and at that juncture, pragmatic fixes need not be applied. As a printmaker interested in geology and compelled by the scientific method, I was searching for artistic solutions that had practical, empirical answers. I wanted to find the place where art and science met. Perhaps after one too many philosophy papers, I decided to close the book on abstract ideas and go out into the field.

Much of my work deals with narrative and the quest for the truth in that space. Truth, for me, was about getting to the heart of what really happened on a cold day in December that has long since passed and can now only be accessed through memories. I have no observable data or evidence. The reality of each moment is a driving concern, and if I can create output of those moments, perhaps they will be easier to analyze and interpret. The prints that I create deal with specific times and places, and I can correlate that nicely with rocks in the field that I learned about through geological field exploration. For instance, pick a memory from your childhood, say, around fourth grade. Were there other people there?

What kind of day was it?

Can you recall what you were wearing?

In the epochs of the history of this earth, that blink in your existence could be akin to a river flooding in the Late Cretaceous. Perhaps some plant matter is trapped in with the sediments rushing over the banks, a picture of that day in the memory of the earth, now lithified. Literally, set in stone.

People will remember things differently, and focus on separate parts of events. Humans get details wrong and let their emotions dictate how they feel about certain memories. The earth, however, could only ever tell you the truth. It records events as they happen, and if you wanted to find out the story – “the reality” – all you need to know is how to read the rocks.

Going forward with this proposition, in late 2012 I set about making an installation titled Wonders of the Rocks: Passages I – IV. It is a collection of various hand-collected granites, gypsum, shale and limestones, placed onto shelves of varying widths. Each shelf contains a set of rocks meant to signify some narrative or implied story amongst the grouping. Some of the rocks used in the piece were covered with my own interpretation, or memory, of that rock so that you could no longer see its real story underneath. The piece is hung low on the wall and arranged in a linear format, meant to be “read,” as one literally reads rocks in the field, looking ever downward. I wanted the viewer to come to this piece and kneel down or bend over as one does when searching for samples. If the meaning of some small passage was lost to the passerby who did not fully engage with the piece, to me this is symbolic of the geologist who loses sight of the details and fumbles even the smallest of notes. A misinterpreted strike and dip of strata could change how one reads a formation entirely, much the same with small intonations in the translation of a foreign text.

I am still working on the idea here between what is meant by the signs and signified, but now I am incorporating cues from language. Maps still play a role to me as guides in making meaning for geological work, but the idea that these rocks can transcend that and become a new language interested me. I’d attempted to construct a meaning, a language, and a truth from reality – actual pieces of the geological record of the earth. I specifically thought of the work One and Three Chairs, executed by Joseph Kosuth in 1965. He gives us an artifact, documentation, and an explanation, but wherein lies the truth? At one point, a member of my committee had to tell me, “You need to let go of this idea of the truth.” I had become stubbornly attached to the idea that each rock was telling me a true story. It is okay to walk away from a set of rocks and misunderstand them, as their language is multifunctional, in a constant state of change (literally from sedimentary to metamorphic to igneous), and open to vast interpretation. There is no one set of passages that can equal one meaning, much the same in language.

But the question persisted: What do we hold the most important? The thing or the idea of the thing?

Along the way I began to think of reality and truth as the same. I could hold a rock physically in my hand, inspect it under a microscope, classify it, and make a very good estimation about how it was formed. Touching a rock was, to me, like picking up a page from the history book of the world. Each rock was a true statement, and if I collected enough of them, I would start to have an alphabet from which to begin a new language.

If these minerals and rocks are important to me as signs, so is what is signified. When I look back at Kosuth’s Chairs, I am reminded of a print that brings this entire endeavor back around again for me. Blue Print, 1992, by Abigail Lane is one of a series of inked chairs that has a felted inkpad in the seat. The placement of the chair so near the wall, the print of the bodily mark hung nearby, almost as evidence but more as connection, calls forth the Kosuth as an artistic antecedent. The print in this artwork acts on several levels: as a record of an action, as a tie-in to the sculpture, and as an image for visual consumption. There is a language beginning to take shape in the print, which is made directly from the body. Almost like a trace fossil found near an outcrop, you can safely guess that one came from the other.

http://abigaillane.co.uk/

I wanted to tell the story of place and of memory with 100% accuracy, but here’s the rub – even in geology you cannot do that. You can make very educated statements and qualified guesses, but there will always be some unknown factor. In the sciences, they warn of “observational bias” tainting your results, but in the art world, observational bias is the most important thing you’ve got.