For those who have yet to drink the digital humanities “Kool-Aid” (it’s the blue stuff they drink in Tron), for the next three posts I will chart my own introduction. My entrance largely follows from attending a seminar that meets twice a quarter on Saturday mornings entitled, “Demystifying the Digital Humanities” (#dmdh). Paige Morgan and Sarah Kremen-Hicks organize the seminar and it is sponsored through the University of Washington’s Simpson Center for the Humanities.

For those who have yet to drink the digital humanities “Kool-Aid” (it’s the blue stuff they drink in Tron), for the next three posts I will chart my own introduction. My entrance largely follows from attending a seminar that meets twice a quarter on Saturday mornings entitled, “Demystifying the Digital Humanities” (#dmdh). Paige Morgan and Sarah Kremen-Hicks organize the seminar and it is sponsored through the University of Washington’s Simpson Center for the Humanities.

In this post I want to outline a brief definition of the digital humanities, and I will conclude by suggesting some things that you can do to advance your own understanding. Because these posts stem from my own introduction, they might be too basic for those already immersed in DH studies. Rather than an in-depth exploration, consider this post as an enthusiastic sharing of information.

Defining the Digital Humanities

During the first session of the seminar we attempted to define the digital humanities. A typical strategy towards definition might ask what a concept “is.” But the organizers challenged us to think about what this concept “does” and what “values” it embodies. The next two installments of this series will cover what you can “do” in the digital humanities. Today, I want look at some values.

Collaboration is one of the main values espoused in the digital humanities. “Instead of working on a project alone,” as Lisa Spiro says, “a digital humanist will typically participate as part of a team, learning from others and contributing to an ongoing dialogue.”[i]

In which case, a digital humanist might post his or her most recent progress, research, or problem on a blog or Twitter feed. Others can then add comments, suggestions, and criticisms. There is also a push toward finding people with the resources to do the job you have in mind (knowing he had the skills, I asked my brother to make the image above for this post). Overall, there is a common avowal among digital humanists that works ought to receive input and support from others before reaching the final product, and in addition, this feedback can come from more people from different disciplines.

Making works more available, as Paige and Sarah stressed, also means a greater willingness to be “open,” even with regards to “failure.” By being more open scholars can overcome the erroneous belief that every “success” equals “positive results.” As in the physical sciences, in the humanities there is little sense in reproducing the same bad experiment more than once. Sharing failures might ultimately lead to less repeat, and potentially more success.

It would be impossible to offer a full definition in this short space, but my conclusion so far is that, without knowing it, many young scholars are already invested in the digital humanities. For instance, writing for the NASSR Graduate Student Caucus blog qualifies as a digital humanist platform and method. I am writing in a public domain, making my interests more open for sharing and criticism, taking risks on what kinds of content I post, and focusing on producing more products more consistently, all of which embodies a DH ethos. During the first seminar in October, upon learning that I already shared many digital humanist values, it encouraged me to go familiarize myself with some of the tools, which I will now discuss.

Getting Started in the Digital Humanities

While not every university hosts a seminar like the one I attended, there are some traveling ones. According to the THATCamp homepage, it is “an open, inexpensive meeting where humanists and technologists of all skill levels learn and build together in sessions proposed on the spot.” These camps take place in cities all over the world and anyone can organize one. Or if you want something more intense, try the Digital Humanities Summer Institute at the University of Victoria (see Lindsey Eckert’s post on this site for an overview).

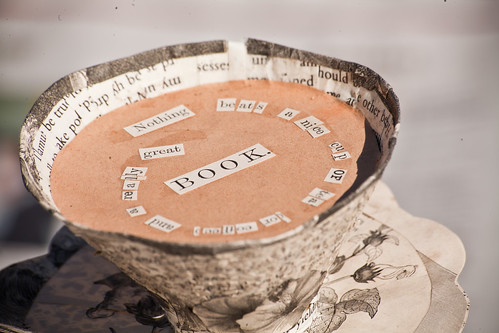

If you really want to jump into the digital humanities fast (this might sound self-indulgent in this context), I think the best method is reading blogs. The problem with blogs is the sheer quantity. But once you find a blog that works, they usually provide a blogroll that includes a list of the author(s)’ own preferences. At the bottom of this page I provide three blogs with three different emphases regarding the digital humanities for you to try (and please respond below if you have others to suggest).

The last thing is coding. It seems scary, but with simple (and free) online tutorials, learning how to code is like getting started with any foreign language: the first day is always the easiest. You learn “hello,” “please,” “thank you,” und so weiter. The difficulties arise later. But anyone who has travelled abroad knows that a small handful of phrases can actually satisfy a large range of interactions. For instance, it takes a few minutes only on w3schools.com to learn how to make “headings” in your blog post (like the emboldened titles above). Headings actually allow search engines like Google to more easily recognize your key words and phrases, which I didn’t realize until I started learning a little code. Ultimately, learning how to code can help you appreciate the rules that govern your online experience.

Last, I think it’s important to divulge why I became interested in the digital humanities. Because my dissertation started to focus more on tools, geometry, and the imagination in the eighteenth century, I found myself on the historical end of digital space. It made good sense then to start exploring current trajectories. But as I hope to show in the next two entries, “doing” digital humanities does not necessitate digital humanities “content.” Your introduction might be more about method, pedagogy, or even values. That said, it is worth having a good reason to invest your time in DH studies. As graduate students, time is always in short supply. But if it’s the right conversation for you, be open, be willing to fail, and enjoy the Kool-Aid.

Some Suggested DH Blogs:

If our blog is the only one you are reading with any frequency, perhaps the next place to go is The Chronicle of Higher Education’s ProfHacker. This blog features a number of authors writing on the latest trends in technology, teaching, and the humanities. For starters, try Adeline Koh’s work on academic publishing.

Ted Underwood teaches eighteenth and nineteenth century literature at the University of Illinois. His blog, The Stone and the Shell, tends to explain DH tools, values, and protocols for “distant reading.”

For a more advanced blog, in terms of tools and issues, I have found Scott Weingart’s the scottbot irregular resourceful, interesting, and it is also a great example of how to up the aesthetic stakes of your own blog.

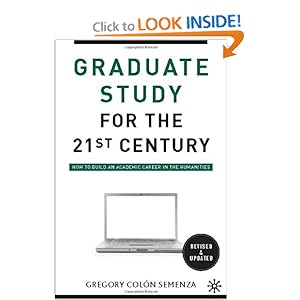

Semenza, Gregory Colón. Graduate Study for the 21st Century: How to Build an Academic Career in the Humanities. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Semenza, Gregory Colón. Graduate Study for the 21st Century: How to Build an Academic Career in the Humanities. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.