This is a post about an issue near and dear to our hearts as bloggers and blog-readers: digital authorship, authority, and recognition. Kathleen Fitzpatrick, author of Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology, and the Future of the Academy, spent two days at Lehigh University. September 12th, she gave a presentation called “The Future of Authorship: Scholarly Writing in the Digital Age” and September 13th, she spoke informally with grad students and faculty. Here’s some food for thought based on her visit.

Fitzpatrick started out with the basics: what kinds of authorship do we as academics value, and why? We value work that is done on an individual basis, thus making it simpler to claim ownership and award credit for the work produced in a final, polished product: I wrote this journal article, did all the research and drafts myself, gave credit through proper citations, and went through the process of revision and peer review and, finally, publication. Lots of people are involved in this process, from the other authors cited in the article, to the editorial board and anonymous peer-reviewers. But we don’t see those names on the by-line.

And this is Fitzpatrick’s point. With so many people involved, we recognize that an article is not published by the author alone, even if we pretend this is the case in our C.V.s and tenure reviews and job applications. Fitzpatrick argues that reading and writing are social activities and are continuing to become even more social  through digital media forums like online journals, blogs, social media, twitter, etc. She claims that we need to rethink the ways that we share information through technology, how we reach and interact with an audience, how we control (if, indeed, we should) quality and authority, and how we give credit for all the labor that goes into commitment to an online community. We need to consider the process as much as the final product, if not more so, in order to benefit from the development of an idea through over time, which is what makes online work so exciting. One of the last points with which she ended her talk was the emphasis on the spread of knowledge for its own sake, in order to let it grow and expand into different forms and fields. Make it as accessible as you can. Certainly, none of us are in it for the money, after all.

through digital media forums like online journals, blogs, social media, twitter, etc. She claims that we need to rethink the ways that we share information through technology, how we reach and interact with an audience, how we control (if, indeed, we should) quality and authority, and how we give credit for all the labor that goes into commitment to an online community. We need to consider the process as much as the final product, if not more so, in order to benefit from the development of an idea through over time, which is what makes online work so exciting. One of the last points with which she ended her talk was the emphasis on the spread of knowledge for its own sake, in order to let it grow and expand into different forms and fields. Make it as accessible as you can. Certainly, none of us are in it for the money, after all.

I don’t consider myself to be hugely involved with all the newest technologies associated with digital information, and things like “open access” are still mysterious to me (and, I’ll admit, I’m still trying to figure out how to best use Twitter, both personally and professionally). Yet, I am involved with blogging (obviously), as we all are and, like many grad students, have been published more online than in print. I love the idea of sharing my thoughts and knowledge with others without worrying so much about polishing them into full-blown articles. Fitzpatrick’s idea of watching a project develop over time is an appealing notion because it gives you a more three-dimensional sense of a scholar and allows you to see the different angles of his or her interests. I also think the immediacy of the internet can be an incredible benefit if used with caution. Sometimes the process of conventional publication takes so long that the information can be all but obsolete by the time it reaches the people who need it. I also like that I don’t feel like I have to make any ground-breaking claims when I share this information. Many of my fellow bloggers have written on very similar topics in the last year, and many other forums of all different kinds have discussed the idea of digital authorship. But we don’t all read every blog out there (couldn’t, in fact), so ideas of absolute originality are a little more fluid. I will not claim to be saying anything completely new here. And that’s okay! I love reading blogs as well as contributing to them for all of these reasons.

Two important questions pertaining to grad students came up during Fitzpatrick’s informal seminar. The first engages with the amount of prestige required to take risks like digital publishing in academics and to convince a conventional academy that such online contributions count towards anything. As we all know, grad students have no prestige. Should we be taking these risks in such a tenuous job market? Should we be putting energy and time into online projects and collaborations if it could be spent on more conventional types of publication? All the “self-help” books on grad school, academics, and writing for publication that I’ve read have either ignored the possibilities of the online world altogether or advised young academics to stay away from them because they don’t “count.” Certainly, there are many problems with being able to publish anything instantly, the least of all being plagiarism, quality control, and authority. It’s refreshing and comforting to hear an established academic say that, yes, blogs and online publications can count and count for quite a lot at that. As Fitzpatrick says, reading, commenting, and keeping up with blogs and other online forums is also time-consuming and a lot of work, but these communities couldn’t exist without the interactive, conscientious, “peer” participant. We all, even by the act of sharing and commenting on online work, claim some part in its continued existence. Such activities create a new kind of credit for work by helping to get a writer’s name out there and recognizable, which can open up so many other opportunities. These kinds of activities should be taken seriously because they are serious! That being said, they are still not taken seriously on a job application, which, as I understand it, still credits conventional print publication (in addition to many other things, of course) and will do for quite some time. Fitzpatrick’s advice is to work towards a balance of traditional and more innovative publications and academic activities: online exposure can lead to name recognition, but it all comes down to that C.V.

engages with the amount of prestige required to take risks like digital publishing in academics and to convince a conventional academy that such online contributions count towards anything. As we all know, grad students have no prestige. Should we be taking these risks in such a tenuous job market? Should we be putting energy and time into online projects and collaborations if it could be spent on more conventional types of publication? All the “self-help” books on grad school, academics, and writing for publication that I’ve read have either ignored the possibilities of the online world altogether or advised young academics to stay away from them because they don’t “count.” Certainly, there are many problems with being able to publish anything instantly, the least of all being plagiarism, quality control, and authority. It’s refreshing and comforting to hear an established academic say that, yes, blogs and online publications can count and count for quite a lot at that. As Fitzpatrick says, reading, commenting, and keeping up with blogs and other online forums is also time-consuming and a lot of work, but these communities couldn’t exist without the interactive, conscientious, “peer” participant. We all, even by the act of sharing and commenting on online work, claim some part in its continued existence. Such activities create a new kind of credit for work by helping to get a writer’s name out there and recognizable, which can open up so many other opportunities. These kinds of activities should be taken seriously because they are serious! That being said, they are still not taken seriously on a job application, which, as I understand it, still credits conventional print publication (in addition to many other things, of course) and will do for quite some time. Fitzpatrick’s advice is to work towards a balance of traditional and more innovative publications and academic activities: online exposure can lead to name recognition, but it all comes down to that C.V.

One of the online authorship issues that grad students in my department have been worried about is the potential complications caused by publishing dissertations online, and this was our second question. Our university automatically publishes all dissertations (and theses) in an online, open access depository, with the option of a one-year embargo. We’ve been concerned about the possibility of being denied publication because our work would already be available through this open access forum, and we have heard horror stories of this happening. One year is certainly not long enough to get something published. However, Fitzpatrick posits this as another positive opportunity to get your name out in order to lead to other publications. I, myself, have cautious, mixed feelings about this related again to prestige qualifiers. I’d be interested to hear what others think about the idea of mandatory open access and what discussions have occurred in your departments about it.

The relationship between academics and digital possibilities is a huge and ongoing conversation, and I’ve really only summarized the ideas Fitzpatrick shared with us and added a (very) few of my own anxieties about online academic networks and forums. I’d like to end by inviting you to participate in this conversation with me. What have you heard about the pros and cons of online publications, blogs, and forums? How much do you value your own participation in such forums as either readers or participants? And the big question: how do we get such activities to “count,” IF we think they should count, in our current positions as grad students? What other issues complicate this question for you?

Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s Blog

How To Do Archival Research (Report of the NGSC-sponsored professionalization roundtable from NASSR 2013)

If you happened to be at the NGSC-sponsored roundtable at the NASSR conference in Boston two weeks ago, you know that it was one of the best events we have organized so far! Truly, it was probably the highlight of the whole conference for me, and that’s saying something. Fun, Interesting, and amazingly useful, the panel brought together five incredibly accomplished (and let’s just say it: frickin’ cool) scholars in our field for a mini-course in archival research. I’ll do my best in this post to translate my notes (along with Kirstyn’s, thanks, KL!) into an efficient reference for anyone preparing to spend quality time in some alluring repository of old books, papers, and objects. If you’re like me, then even if you don’t have a research trip in the works right now, you might just find yourself itching to plan one. Anybody want to meet up at the British Library?

Special thanks again to our panelists Michelle Levy, Devoney Looser, Andrew Burkett, Dan White, and Jillian Heydt-Stevenson for sharing their insights. I have taken the liberty of organizing this post according to topic (rather than strictly by speaker), but have noted broadly who covered what. Now, here we go!

How to integrate archival research into your studies (Michelle Levy)

Before you embark upon archival research, take some time to approach it thoughtfully and deliberately.

- Consider what types of research actually requires the use of archival materials—that is, stuff that has not been republished in other more readily-available formats, or that contains vital information in its original material makeup. Book History and Material Studies projects require this, as do many kinds of academic side-projects such as critical editions, biographies, or edited collections of letters. Though these types of publications will not qualify a person for tenure, they become very useful resources; you might ask an advisor if they have such a pet-project in the works that you could help with—or eventually, you could do one of your own. (Also, think about where/how you might publish such a project, including in digital formats—check out PMLA’s “Little-known Documents” as an example).

- Be sure to build in TIME; archival research cannot be done at the last minute. You need time to sift through materials before you find the gems that matter. You need time to write applications for research fellowships, including the lead-time for letters of recommendation. You need time to learn the research techniques that reveal the documents’ secrets (see next item).

- Build research skills before you go. Take a course in book history or bibliography if you possibly can. Use the Special Collections of your home institution to get a sense of how they work, how often they contain non-catalogued materials, and how vital it is that you form a good relationship with the librarians.

- Take time to figure out WHERE you will need to go in order to look at the documents you need, and whether that institution provides any research fellowships. Some large institutions in the US do (like the Huntington, the Pforzheimer, and the Harry Ransom Center); most institutions in the UK do not (in which case, you might apply for a fellowship from your own university or some other funding body).

How to apply for research fellowships (Devoney Looser — see full text of her very useful handout HERE).

- Remember, the surest way to not get funding is to submit a shoddy application. You are in competition with lots of other smart people.

- Give your advisors plenty of lead-time to write you letters of recommendation (a month is polite).

- Show that you have specifically researched the holdings of the institution you plan to visit. Use their online catalogues and finding aids, talk to others who have researched there, and even consider calling and talking to the librarians and curators (as long as you’ll be asking them smart questions, and not ones you could have answered yourself if you had just looked at their website).

- The Project Narrative is the most crucial part. Don’t let another critic’s voice take center stage. Explain WHY your research is exciting and important. It is not enough to “fill a gap”—you must explain WHY the gap needs to be filled. And never begin your narrative with a quote from someone else!

- Remember that you’re writing to a committee that comes from several disciplines, not necessarily including Romanticism. Be sure that an educated non-romanticist could understand the importance of your project.

- Don’t give up if you don’t get the fellowship! Seek feedback, improve your application, and keep trying.

Tips for planning your research trip, including some packing essentials (Michelle Levy et al)

- When planning your research trip, travel off-season if you can; it will be cheaper and libraries will be less crowded, which means you will get your books faster and librarians will be more available to help you.

- Learn the archive’s rules and procedures before you go, so you don’t waste valuable time when you’re there. You can usually order your books in advance, and occasionally you have to do so.

- Read as much as you can before you go, including electronic forms of your primary documents, so that you can focus your precious time on the info you can’t get otherwise. Software like Adobe Professional is useful for taking notes on PDFs.

- Use a number of resources to plan the trip. Contact the archivists (with smart questions, of course); they are really helpful.

- ALWAYS get a letter of endorsement from your advisor, printed on university letterhead and signed in BLUE ink. Some institutions will not allow you access to their archives without this. Also, be sure to check whether they have other requirements, such as more than one form of ID, or a passport, or proof of current address.

- Every institution will have its own rules and restrictions on what you can bring into the archives, (be sure you understand their policies involving photography and reproduction) but pack yourself a basic “research baggie”—it will probably include pencils, a ruler, some paper, a magnifying glass, your laptop, a camera, and a jacket or sweater—libraries are CHILLY!

How to get the most out of your time in the archive itself (Andrew Burkett and Dan White; check out the full text of Andrew Burkett’s talk HERE)

- Have a plan, but be open to discovery! Let the archive drive you, but have a clear sense of your research questions (start with the broadest one, which is “I want to learn everything about _____.”)

- Expect to be overwhelmed completely by the avalanche of information you might uncover.

- MAKE FRIENDS with the archivists and curators. They can help give you a roadmap through those materials and focus your search. Some archivists will be very helpful, others markedly frosty; kill them all with kindness! They hold a lot of power, and if they decide they like you, their input can radically impact your work.

- Allow yourself to enjoy your time while searching through the materials. Talk to other people working there. These work sites are dynamic and alive and exciting.

- Embrace the fellowship in your fellowship! Think of time at the archive as professionalization through sociability. Learn how to talk about your work in a way that excites other people who are not necessarily in your field.

How to manage the notes and pictures you gather (Dan White)

- Approach your note-taking systematically; essentially what you’re doing is amassing a body of notes from which, at a later point, you are going to produce scholarship. The more clearly and obviously you can organize and tag what you gather, the more you’ll thank yourself later. You’ll likely develop a system that’s unique to you, but as you do, imagine how your future self will be using your notes. You want your notes to help you create ideas for scholarship.

- ALWAYS record full bibliographic information for every item you look at!!

- Have a system of naming your electronic files; long names are useful and perfectly acceptable; include key info such as author surname, keywords from title, date, other keywords.

- Include cross-references for yourself, as you think about linkages you’re finding. Within the file of notes on a given item you can include items like “See ‘full name of file’ and ‘full name of file.'”

- In your file for each item, clearly differentiate your transcriptions from your meditations (perhaps with different-colored text?), but definitely include BOTH! Your epiphanies will be easily forgotten in the deluge of information you gather, so cherish each fleeting thought and keep a running narrative for yourself.

- Don’t forget that there are different kinds of notes; if an electronic copy of a given text is available, you can download it and (with proper software) take notes on the PDF. i

- On a shorter visit (one month or so), it’s probably best just to spend your time gathering as much info as you can. If you have a longer research period, you’ll probably want to work in some more formal writing/processing sessions for drafting the chapters or articles you’re working on. Keep in mind, though, that the research narrative you produce in your notes is part of that drafting process.

How to go about locating and working in private, lesser-known, and otherwise unconventional archives (Jill Heydt-Stevenson)

Occasionally you might find yourself searching for texts or objects that don’t end up in academic institutions. (Professor Heydt-Stevenson spent her summer researching collections of Paul and Virginia memorabilia, everything from handkerchiefs to cuckoo clocks, things that have mostly ended up in the hands of private enthusiasts who have all sorts of different reasons for collecting, and house their collections in their homes). So, how do you go about finding such repositories, and how can you prepare to use them?

- Search for clues about these kinds of collections on the internet, and definitely ask anyone you can think of who might know about anything useful. If you have friends locally, they can give you a spring board for people who won’t be on the internet. When trying to set up a visit don’t be afraid to use the phone! Keep in mind that some private collectors are older, and may hail from an era before email was so prevalent, or may live in the countryside with spotty internet access.

- Be prepared for the personalness of the research, and of your interactions with the collectors and their space. Keep in mind that you may be in someone’s home, going through their prized possessions, and your people skills will be very important.

- Be prepared for a huge difference between what the private collector does, versus an institution. What matters to them may not be what matters to you, and you must respect this. There will likely be no catalog, and little recorded information or analysis for each object. You will also likely not have a lot of time with the collection. These are huge challenges for a scholar.

- Bring notepaper as well as a computer to take notes in this house. There may be no wifi.

- Have a really good camera on you – not an iPhone camera. Take lots of photos!

- Be sure to ask the curator and owner if they want to be cited. Some do, and others feel intensely protective of their collections and do NOT want publicity.

- Be prepared to see one thing, or 300 things, depending on the situation.

- Be prepared to do a ton of socializing and talking, like a job interview. The curators will likely be thrilled that someone is interested in their collections, and will want to know all about what you’re planning to say about them. All this talking will take up some of your research time, but be gracious and keep in mind that it will likely enable you to do more research with the collection in the future.

Happy researching, everyone! And if you want more information, be sure to check out our collection of posts on Libraries & Archives. (You can access this from the drop-down menu for “Categories” on the right side of the page).

“Writing a Winning Fellowship Application” by Devoney Looser

Devoney Looser

Department of English

P.O. Box 870302

Arizona State University

Tempe, AZ 85257

Devoney.looser@asu.edu

http://www.devoneylooser.com

NASSR 2013 Graduate Caucus Roundtable

Writing a Winning Fellowship Application

Know your project, and research the competitions that best fit your needs.

- Dissertation fellowships

- Support late-stage (usually final year) completion of your dissertation.

- Look at Academic Jobs Wiki page, Dissertation Fellowships Page

- Consult with your advisers/mentors

- Long-term fellowships

- Post-doctoral or pre-doctoral, 6-12 months, to complete large projects

- May allow you to dictate your whereabouts

- May involve residency in a particular institution/library

- Long-term fellowships at libraries may involve agreeing to give a lecture but rarely involve teaching

- Post-doctoral fellowships at universities usually involve teaching

- Seek advertisements through your professional organizations

- Seek advertisements through research institutions or libraries

- Consult with your advisers/mentors

- Short-term fellowships

- Two weeks to 3 months to travel to a particular collection for research toward a book, book chapter, or essay

- Requires SPECIFIC knowledge of collection and why it is necessary to undertake your research there

- Seek advertisements through your professional organizations, listservs, institutions themselves, etc.

- Some fellowships offer residency and access but not travel (e.g. Chawton House Library). Be prepared to combine resources/funding

- Consult with your advisers/mentors

- Workshops

- These fellowships require you to work in a group to complete readings, participate in conversations, and/or share your research in progress.

- NEH Summer Seminars and Institutes for College and University Teachers now reserve two slots for graduate students.

- Start now to track early post-doctoral opportunities, e.g. National Humanities Center Summer Institutes in Literary Studies: http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/sils/

- Graduate student travel to conferences

- Usually require an accepted paper, application, and recommendations

- Seek advertisements through your professional organizations

- Seek internal awards at your institution (department, college, university, graduate students organizations, student fees, etc.)

Leave yourself plenty of time

- The surest way not to get funded is to do rushed, last-minute work.

- Produces shoddy applications

- Prevents you from building a reputation as someone who does smart, careful work

- Frustrates advisers/recommenders who want you to be known for doing smart, careful work

- Remember: a fellowship is not a lottery; it’s a competition. Train for it!

- Applicant packets have many parts, all of which are important.

- Project description (length specified; follow it!)

- CV

- Letters of recommendation (2-3)

- Budget

- Share your application packet with peers and trusted others for feedback.

- A month prior to the deadline, ask recommenders whether they would be willing to write for you.

- It is polite to give your recommenders a copy of the draft of your project description after he/she has agreed to write.

- The more information you offer a recommender (project description, CV, etc.) the more detailed a letter he/she will be able to write.

Sell your project

- Project narratives: a genre to study and master.

- Start with the big picture

- Your first paragraph should give readers the information they need to answer this question: “This writer is studying (TOPIC) because he/she is trying to discover (QUESTION) in order to understand (PROBLEM) so that (ARGUMENT).” (The Craft of Research)

- What does your project offer that advances current conversations and debates? Why should scholars in your field(s) be interested in what you are doing?

- Do not rely on “This fills a gap!” How and why?

- Show that you are joining ongoing conversations/debates, but don’t let other voices have the floor for too long.

- Reference some names or concepts, if you must, but this is not the place for long quotations from other scholars.

- Why start a paragraph with another critic’s name, if you can help it? Make an argument or a concept the first part of a topic sentence, not the critic.

- Seek examples of successful applications.

- Do you know anyone who has gotten one of these fellowships recently who might share his/her application packet? Does your adviser?

- Look at the people who received funding in past years (often listed on the website). Do you have connections to any of them to ask for advice or feedback on drafts?

- Scrutinize what kinds of projects were funded. Does yours seem to “fit” in its title, topic, conception, and/or scope?

- Large organizations (e.g. NEH) will sometimes be willing to share model applications upon request.

- Start with the big picture

- Remember: you are writing to the committee reviewing applications.

- Who is on this committee?

- It is likely that they are academics and affiliates of the granting agency, not necessarily in your precise field.

- They may be past recipients of these fellowships.

- They will likely be rank ordering applications based on the worthiness of the project, its promise, and demonstrated need/fit.

- Consider whether you should enlarge your rhetorical frame or give more cues to readers not directly familiar with your subfield.

- Include full names, titles, dates for any texts/authors you mention that may not be well known to evaluators.

- Consider adding brief descriptive adjectives on first mentioning a lesser-known figure, e.g. “the once-celebrated historical novelist Jane Porter.”

- Be as clear and direct as possible.

- Present any needed background information as part of an argument, not as part of a summary. Don’t lecture your readers; lead them.

- Get rid of: cute or clever titles (use descriptive keywords + argument) and opening paragraphs that are flying at 30,000 feet (“In the beginning, there was literary criticism.”).

- Who is on this committee?

- Read more academic self-help literature on this question.

- “The Art of Writing Proposals” (SSRC) available for free download

- http://www.ssrc.org/publications/view/7A9CB4F4-815F-DE11-BD80-001CC477EC70/

- Their advice, as told in subtitles: Capture the reviewer’s attention, Aim for clarity, Establish the context, What’s the pay-off?, Use a fresh approach , Describe your methodology, Specify your objectives, Final note

- “The Art of Writing Proposals” (SSRC) available for free download

Show compelling need

- How will this agency determine need, and do you “fit”?

- Read the call for applications. What kinds of need are you asked to demonstrate?

- Is there a specific way you can show rather than tell, e.g. not “I am but a poor graduate student,” but “This fellowship would make it possible for me to complete needed research, as my university does not currently fund graduate students’ international research travel.”

- Demonstrate knowledge of the program/library you want to invest in you.

- In ways subtle and unsubtle, echo the keywords in their call.

- If applying for a travel-to-collection fellowship, include 1-2 paragraphs (often toward the end of the project narrative) in which you specifically name the resources that you plan to consult and why.

- Research the collection in question. What does it have that is unique? What are its strengths? Know your library!

- Name the specific categories of materials and even specific titles that you will plan to consult and how they may meet your research needs.

- Make sure that you are not proposing to travel to read something easily accessible elsewhere (Google books, ECCO, NCCO).

- Do not suggest that you will complete more reading/writing than you can reasonably do in the amount of time stipulated.

- Be specific about outcomes. “In three months, I will finish my book” is much less persuasive than “During the first two months of the fellowship, I plan to revise chapters three and five, using xyz. In the third month, I propose to complete research for the book’s conclusion, using abc.”

- Budget realistically

- Ask your adviser or someone who has applied previously to share a sample budget.

- Use categories that are allowable within the grant.

- What are the actual costs for airfare, hotels, etc.? Use them. Reference them. Estimate upward if you would be traveling at a time it is more expensive.

- Consult federal per diem rates for a particular city to estimate costs for lodging and meals.

- Does your university’s Office of Research help with budgets?

- Never, never, never give up!

- All of us have been rejected. Multiple times. Dust yourself off, and try again next year or in another competition.

- Seek constructive feedback. Ask trusted others, not the organization itself, why your application might not have been successful.

- Some large organizations do allow you to ask for comments on your application (e.g. NEH). They specify this in their instructions.

[Editor’s note: published with permission of the author]

“Maximizing (and Enjoying) Research Time in the Archives” by Andrew Burkett

Andrew Burkett

Assistant Professor of English, Union College

Roundtable Talk: “Researching in the Archives”

NASSR 2013, Boston University

August 9, 2013

11:30-1:00 PM; Conference Auditorium

“Maximizing (and Enjoying) Research Time in the Archives”

I wanted to begin my brief remarks today first by thanking Kirstyn and her co-organizers for putting together this exciting roundtable and for inviting me to share some of the story of my own experiences in archival research as well as some ideas about how we might all approach future archival work a bit more efficiently and with, perhaps, a bit more enjoyment. In doing so, I’m going to limit these remarks to thinking about how to maximize—and to appreciate more fully—one’s time once at the archival research site. And I wanted to note too from the start here that I’m basing these insights largely on my own experiences while working with the Charles Darwin Papers while a Visiting Scholar in the Manuscripts Room at the University of Cambridge’s University Library (or the UL, as it’s affectionately abbreviated). So, these notes are made in relation mainly to my work at a single-author archive, and some of these ideas thus might not translate seamlessly into other forms of archival research. That said, I’ve worked to keep my remarks broad enough so as to speak—as best as possible—about “Researching in the Archives.”

A few very brief notes about my archival research project: I spent roughly two years—on and off—completing the research for the final chapter of my dissertation (which focuses on the role of the idea of “chance” in nineteenth-century cultural and scientific production) at the UL, where I was looking at Darwin’s unpublished manuscripts concerned with the concept of species variation and evolution. Before leaving Duke and even up until my first days of arrival at Cambridge, I envisioned my archival research as an unearthing of what I—at the time—speculated to be Darwin’s investments in Romantic poetic forms and philosophies, and I hoped to substantiate that thesis by uncovering in the unpublished papers evidence (textual, conceptual, etc.) of an indebtedness to Romantic notions and representations of the aleatory. Unfortunately, though, I found very little evidence of this sort, and while some of these research endeavors were indeed fruitful to some extent, I found myself moving into something like a state of panic, as my assumptions about what I would find among the papers were rather quickly overturned. And this leads me to my first major point about working in the archive—be more than willing to adjust your research program as and when you are in the act of investigation. The more rigid I became in my initial weeks to seek out such evidence, the more I realized that I wasn’t paying the archival materials the respect that they deserved—indeed, that they demanded. So, I feel that while we certainly need to bring with us expectations of what would be successful outcomes of research, we also need to be able to adjust to the contingencies of the archive. Once I began to let go of that desire to find what I believed I was seeking, I actually started to stumble upon so many new forms of evidence that took my work in radically novel and exciting directions.

Fortunately, these initial interests led me to uncover—by chance—a largely unpublished sector of the archive dealing with what is referred to by the curators of the Darwin Papers as Darwin’s “Botanical Arithmetic” drafts. Of course, I won’t go into the details of this find, but I’ll note briefly here that, while Darwin made these numerous and extensive statistical calculations involving the bio-geographical distribution of continental plant species just before the 1859 publication of the Origin of Species, only a few scholars had investigated, at the time of my research, Darwin’s botanical studies that played such a crucial role in his discussion of the key evolutionary concept of ‘variation under nature’ in Chapter II of the Origin. So my point here, which builds off of my last, is that we must be prepared to evolve as archival researchers if we are going to make new discoveries in unpublished materials. And this leads to my next piece of advice as well: this sector of the archive opened wide before me—which was obviously exciting and promising—but as it did so, I was quite overwhelmed with the number of volumes and boxes of documents dedicated to these complex mathematical calculations. I was also extremely surprised to find that even with an author as famous and celebrated as Darwin that some of these materials were impossible to seek out via electronic research methods and that I had to do the leg work of catalogue searches and even sometimes had to stumble around blindly through volumes and boxes in this sector—page by page, or leaf by leaf—as a number of the boxes were (surprisingly) not fully marked or catalogued, given the relative obscurity of these drafts. So, part of my second major point here is to expect at some point—and even perhaps for several days at a time—to be overwhelmed completely by the avalanche of information that you will likely trigger in your work, regardless of your project. The question then becomes: how does one move through such mountains of information to seek out those five or ten documents that will be most important for your argument and that you might wish to transcribe or even pay large sums to have imaged? My answer here is a quite simple one: befriend the archivists and curators and even other researches working among the papers in which you are interested. Upon finding these materials, I quickly sought out and turned to Adam Perkins, the Curator of Scientific Manuscripts at the UL, and he proved to be an invaluable source of information about the micro-sectors of the “Botanical Arithmetic” drafts that made the most sense for me to look into first (and even provided me with an order through which to move among the papers) based upon the more global concerns of my chapter focusing on the concept of chance—and more specifically to Darwin—the development of his theory of organic variation. Adam let me know that (by chance) David Kohn, one of the few scholars who had studied and written about these papers, had been seated only a few tables away from me for several weeks during my work in the Manuscripts Room.

This serendipity leads me to my third and final set of remarks—personal observations really—about working in the archives: really do allow yourself to enjoy your time while searching through the materials. David was more than excited to talk with me about my project and to give me advice about things such as where I should look next in the archive and ways to proceed efficiently with the work (many of which I’m borrowing from in my own remarks today), and I soon realized after befriending Adam and David that archival research sites are just as—or perhaps even more “alive,” so to speak—as any of our other work sites (e.g., our departments, our classrooms, our offices, etc.). Archival centers are extremely dynamic, unpredictable, and—as such—exciting places: they can certainly be intimidating and overwhelming but, more often than not, if we are willing to accept their contingencies and surprises, they are almost always prepared to greet us with hospitality and—most certainly—with vitality.

[Editor’s note: published with permission of the author]

The First-Year Ph.D. Experience: Time Management

Introduction: This post marks the second of a series with perspectives on the first year of pursuing grad studies at the doctoral level. The first looked at language requirements, with my spring German reading exam serving as an example (which was–in fact–passed!). As promised prior, this next piece engages with the crucial issue of time management. It’ll be followed by a final blog in the series on theory and methods.

Broadly, something that I struggled with as a master’s student, and admittedly still struggle with at the Ph.D.-level (hence making myself write this during a particularly strong summer lull in productivity), is how to manage my time so as to consistently produce successful and (just as important) tangible results. For me, as I’m sure the case is for most, my time always seems impossibly short and the tasks before me infinitely many. As a solution, at the start of last fall, I committed myself to mapping out long- and short-term goals in concrete ways using material means that made them constantly visible to me on a day-to-day basis. In what follows, I outline these methods. Namely, there’s two technologies of time management at play: the dry erase board and my pocket notebook. When I did my best work this year, looking back, I relied on these things without exception.

Dry erase boards & the Moleskine Notebook: Keys to my first year: While my master’s program went well enough, essentially I had one central goal in mind: to be accepted to a Ph.D. program. Then, it was somewhat easy to conceptualize how I went about my work according to the priorities of finishing a fifty page thesis, completing application materials, and working on NGSC blog posts in between preparing a couple conference presentations. However, once I began gearing up for the demands of a five-year doctoral program in the summer, I quickly recognized matters would be considerably more difficult when the hurdles are both more complex and spaced out. In order to meet the new challenges that were ahead I decided early before the term started to attempt to change how I pursue my work, looking to take a much more organized, disciplined, and thoughtful approach than I had before. I found the basis for this in Donald Hall’s really great book The Academic Self: An Owner’s Manual, which stresses the importance of careful, but flexible, planning. Consequently, when I got to Evanston and it was time to hit the bookstore, I purchased two large dry erase boards and one dry erase calendar. I put them up around my apartment in places where I would see them constantly. I also picked up my first Moleskine notebook (on one Kurtis Hessel’s good advice, which became one of many over the course of the year). The first board would have the long-term goals for a five year plan, on the second the year’s objectives in monthly columns, and on the calendar and notebook (which I always tried to have with me, for constant accountability) how these goals would take shape on a week-by-week/day-by-day basis.

Long-Term Ambitions, Short-Term Goals, & Task Lists: On one of the large boards I took care to mark down all of the major milestones of my academic program: language exams, the second-year qualifying paper, third-year comps, and dissertation prospectus to follow. I also added a handful of other ambitions I’d like to fulfill, having to do with objectives like publications and fellowships for which I’d like to apply. Like most incoming graduate students, I felt initially intimidated by the list. But, breaking the larger objectives into tasks on a five-year timeline (while knowing the diss. phase may take longer) made things seem more manageable. For the first-year, beyond coursework, I decided to focus on completing both language requirements, have my qualifying paper selected from my seminar papers written in my first three terms, and (later) to apply for a museum curatorial fellowship. At the start of every month I would transpose the Year-Based Goals onto the calendar and at the end of each day I would write down what I wanted to complete on the day following in my Moleskine. I realized, for instance, that I needed to complete about a chapter per day (or 5/week) from my German For Reading Knowledge textbook in order to utilize German reading language resources for my winter/spring term research to feel prepared to take the exam in May. Yet, as the year progressed, I realized I needed to be much more adaptable on the second shorter-term tier of things, since contingencies came up that in many cases delayed (and in some even thwarted) what I wanted to get done when. The key, however, was that crossing off tasks on multiple lists made my development and progress more gratifying and tangible in ways I hadn’t felt before.

Conclusion: At the end of this year I’m convinced that I owe a great deal of my growth, which I felt came at a quicker pace than before, to thinking about–and managing–my time more conscientiously. This is not to say I followed my own system perfectly. In the winter term, for instance, it became more difficult to sustain the necessary effort and I became less committed to noting the next day’s tasks. As a result, things slipped significantly and I worked into deadlines more than I would have wanted. Moreover, I should have realized to a greater extent than I did initially that, even with great planning, flexibility is key and keeping a “negatively capable” eye towards productive uncertanties and new possibilities one can’t plan for is important. I hope to improve upon all of this in subsequent years. Ultimately though, I felt that ideas gleaned from my first-year in this regard multiplied the number of moments in each day “Satan couldn’t find” and where I could be most productive. Of course, though, while I’ve been pleased with my own experiments this year, I’m of the mindset that a dialogue on how we think about time and structure our lives and work is better. So, I’d very much like for this piece to be a cause for conversation where other ideas on time management might be circulated.

Digital Humanities: My Introduction 1.3

This post is part of a three-part series charting my introduction to the digital humanities. My entrance largely follows from attending a seminar that meets twice a quarter on Saturday mornings entitled, “Demystifying the Digital Humanities” (#dmdh). Paige Morgan and Sarah Kremen-Hicks organize the seminar and it is sponsored through the University of Washington’s Simpson Center for the Humanities.

As the spring term ends for the 2012-2013 school year, I want to conclude this series of posts with some reflections on introducing the digital humanities into my pedagogical practice.

Digital Humanities or Multimodal Composition Class?

The course I designed in March differs greatly from the class I ended with this week. My assignment was English 111. As the course catalog describes it, 111 teaches the “study and practice of good writing; topics derived from reading and discussing stories, poems, essays, and plays.” While the catalog says nothing about the digital humanities, so long as we accomplished the departmental outcomes, my assumption was that a digital humanities (DH) component would only provide us with new tools for thinking through literature and writing.

It was an innocent assumption.

The main issue was scope. For my theme I chose “precarity,” which Judith Butler describes as that “politically induced condition” wherein select groups of people are especially vulnerable to “injury, violence, and death.”[i] Because there are so many “precarious characters” in Wordsworth and Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads, I used this collection for my primary literary text. In addition to investigating precarity, with the Ballads students could also explore multiple genres and how the re-arrangement of poems alters the reading experience. Third, I wanted to use a digital humanities approach. By a DH approach I mean that I would encourage digital humanities values with regards to writing (e.g. collaboration, affirming failure), using digital tools, and learning transferable skills.

By the second half of the course it was clear that the students were confused about the concept, unhappy with the text, and struggling to understand the purpose of the values, tools, and skills. During the second half of the course, I lost hope for my big collaboration project and I dropped the emphasis on the Ballads, focusing instead on rhetorical analyses of blogs and news sites addressing issues of precarious peoples and working conditions, which was especially timely after the recent tragedy in Bangladesh.

Without the literature component, students began to feel more comfortable with the tools and concept, which led to greater motivation and better papers. On the downside, these students signed up for a literature class, which I basically eliminated. The triad of concept, literature, and method should work. But I found that if all three areas are of equal difficulty you may risk blocking success in any of them.

The “transferable skills” were perhaps the most successful part of the course. It is not the case that my classes didn’t teach transferable skills prior to my digital humanities emphasis. But as Brian Croxall has emphasized, we can teach more of them. As far as the digital humanist is concerned, more “skills” is tantamount to learning how to use more tools, which I translated (perhaps erroneously) as more media. So this term, all of my students built websites and blogs.

From building blogs and websites students learned firsthand how medium shapes what we can write, how “writing” might necessarily include design and management, and rather than give a tutorial on how to build these sites, I showed students how they could use Google to search for help on their own. The transferable skills were twofold: build an online platform to host your work (which alters what you can present and how), and learn where and how to find answers to your building questions (and rather than “good” sources, I stressed more of them). While initially these sites were less than satisfactory, by the end of the class students began to realize the potential and implications of the medium, which prompted several of them to re-build their sites during revision phases, taking more time with the organization of pages, images, background colors, and hyperlinks, and then explaining why these changes were important.

The websites and blogs showed signs of success with regards to “building skills,” but these platforms might belong less to the digital humanities and more to “multimodal scholarship.” As the organizers of the Demystifying the Digital Humanities seminar stressed during the April 14th session, digital humanists use their tools to “produce” scholarship, while multimodal scholarship means using tools to “display and disseminate” traditional research. These differences are a bit blurry for me still, but the blurriness might be accounted for by the fact that some of us are “trickster figures” occupying multiple regions on the plane of digital scholarship, as Alan Liu explains in the most recent PMLA (410).[ii]

But Liu adds greater clarity to these distinctions when he explains how a digital humanities project uses “algorithmic methods to play with texts experimentally, generatively, or ‘deformatively’ to discover alternative ways of meaning” (414). The algorithms may be out of reach for English 111 (and me!), but by using Google Sites, Blogger, and Ngram many students were cracking the digital ice and playing. In other words, these basic multimodal tools might be a useful first step towards transferring to a more involved and complicated DH project.

For such a class to be really successful it will require much more planning. For the fall, I am refining what I have rather than adding more tools to the mix. Until I do some serious text mining of my own, it might be safer to design a “writing with digital media” course. But now that Pandora’s (tool) box is open, I don’t see it closing in the future.

After attending the Demystifying the Digital Humanities seminars and writing these posts, I wonder if my introduction has actually led me to media studies instead. My suspicion is that I will touch both areas, because it is ultimately the task or problem that will determine the approach. However, and I believe Liu also demonstrates this point, the digital humanities as a method might prove to be a problem or task generator. With these tools we will become like Darwin returning from the Galapagos with all those varieties of finches sitting on his desk, asking what all these birds have to do with one another. Perhaps the moral should be: the more materials the bigger the questions.

Digital Humanities: My Introduction 1.2

This post is part two of a three-part series charting my introduction to the digital humanities. My entrance largely follows from attending a seminar that meets twice a quarter on Saturday mornings entitled, “Demystifying the Digital Humanities” (#dmdh). Paige Morgan and Sarah Kremen-Hicks organize the seminar and it is sponsored through the University of Washington’s Simpson Center for the Humanities.

The first post in this series attempted to define the digital humanities by considering some of its values. Today I want to make two points regarding what a digital humanist is and does. First, a digital humanist is not the same thing as a scholar. While the same person may occupy both roles, these roles nevertheless perform distinct tasks. Second, the digital humanist is distinguished by the tool set, and those tools are primarily for the purposes of visualization. So let’s explore these two points in greater detail, and I’ll conclude by looking at one of the many tools you can use in your own introduction to the digital humanities.

Tools, Tools, Tools!

On the last day of our Demystifying the Digital Humanities seminar (May 4, 2013), the organizers drew our attention to something surprising with regards to digital humanities scholarship: it may not be scholarship, at all. Many of those coming to the digital humanities already know how to conduct research, build and organize an archive, and employ “critical thinking” in order to arrive at some conclusions. The final step is often a presentation of these conclusions in the form of a written essay or a book.

Rather than adding data and conclusions in the scholar’s process, the digital humanist multiplies the perspectives and the media. The digital humanist uses tools in order to view and present collected data in the form of a diagram, graph, word cloud, map, tree, or timeline (or whatever you invent). Because a visual image allows us to see the “same” object or data set in a different way, the tool increases the scholar’s range of conclusions. So the scholar must demonstrate significance, but it is the tool that functions as a “bridge” for the sake of achieving that end.

Given the literary scholar’s tendency toward close reading, certainly an abstract diagram of the work(s) will lead to a less insightful reading. But here we are operating as if the tool provides a conclusion, which is the wrong assumption. The tool does not provide conclusions. The tool only allows us to see more at once.

My close reading of a romantic poem might be the most accurate, interesting, or revealing, but if I can see the same information in relation to more texts, across spatial and temporal fields, my tools will make conclusions regarding historical time periods outside my area of specialization. Wrong again! The map or graph only demonstrates correlations, intersections, and divergences. It is then up to the scholar to investigate those areas.

As the historian Mills Kelly says in his contribution to Debates in the Digital Humanities, “instead of an answer, a graph…is a doorway that leads to a room filled with questions, each of which must be answered by the historian [or literary scholar] before he or she knows something worth knowing.”[i] In this sense, the diagram functions like a treasure map that makes the X’s more explicit. And while that map will tell a scholar where to dig, it cannot tell us why the artifacts matter, what they mean, or how they are useful.

If the burden of the conclusion falls on the scholar, the digital humanist has aesthetic and logistic responsibilities. The digital humanist might ask questions like, “What kind of visualization most effectively represents my data?” It will also be important to consider financial issues like cost and maintenance. Often times, visualization software is free. But when depending on others for your tools, there are risks like the issue of ongoing support. If I use an online tool made by a company that suddenly “disappears,” I may have to go shopping. And let’s not forget the attachment people feel for an accustomed piece of equipment. Whatever tool one chooses, the old rule applies: backup your files. If you lose a tool you have only lost the medium through which you represent your information. Lose your information, and—well…

But everything we do comes with risks. To balance your decision as to whether or not you want to use these tools, I suggest having some fun with them first. An easy and fast way to see the benefits yourself is through IBM’s Many Eyes, a website devoted to free visualization software. The disadvantage is that Many Eyes’ visualizations must remain online; on the other hand, the site is so easy to use that you can test the water within minutes.

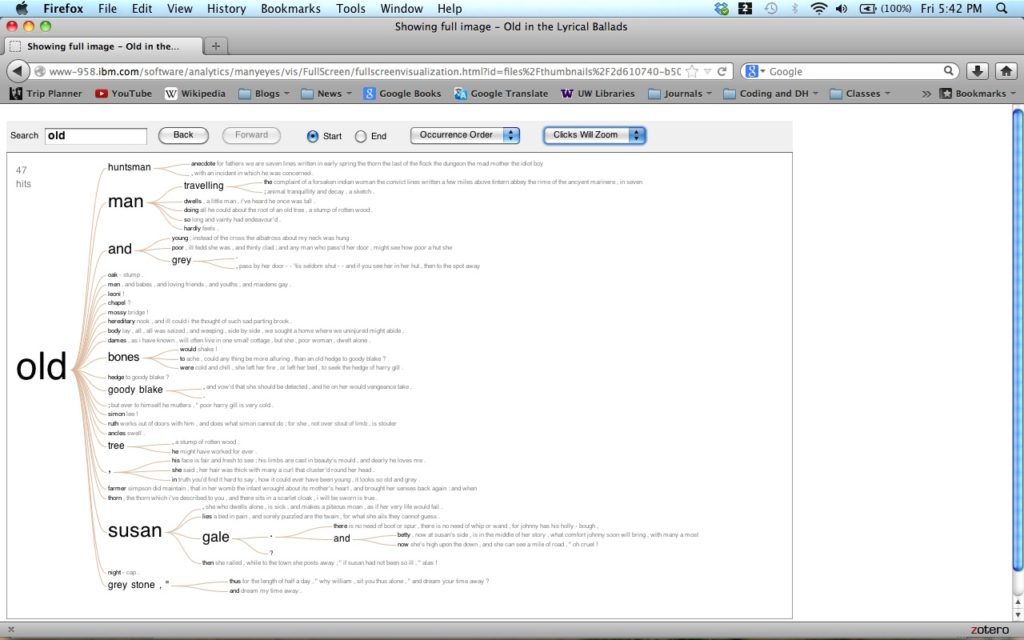

Below is a screenshot of a word tree I made from the Lyrical Ballads. In order to generate the tree, first I use the browser in the “data sets” to find the Ballads, which someone had already uploaded. Then I click the “visualize” button and select the first diagram option, “word tree.” From here I can enter any word from the Ballads that I want to explore. The 1800 edition begins with an “old grey stone,” so I enter “old,” which catches 47 hits. A diagram appears illustrating all the instances of “old” and how it connects to the words around it. Now imagine doing this with hundreds or thousands of texts. Many Eyes won’t tell you what all those connections mean; rather, it allows you to see them in the first place.

For a closer look at this image, click here.

Rather than “new,” the word that best describes the advantage of digital tools is “more.” A Concordance to the Poems of William Wordsworth does something very similar to my word tree above because the book also supplies all the instances of “old” in Wordsworth’s poetry. But with digital tools, I could add the concordances to Virgil, Spenser, and Milton, as well as those writing manuals, law documents, and political pamphlets. Then all of these texts can be incorporated into the same visualization. In a way, these possibilities make me less nervous about the future of scholarship. Now I can see more ways of lengthening the narratives I was already generating, and find more to explore.

Beyond aiding our own scholarship, the visualization helps communicate what we do as scholars to a broader audience. The thing to remember is that the tool is not a justification in itself and it does not make one’s role as a scholar more relevant. But with these tools we can better demonstrate the power of the media we study to others using a medium held in common across discipline lines. Equally important, by working with these tools, we are in a better position to illustrate the necessity of the scholarship that actually makes these images meaningful.

The Demystifying the Digital Humanities seminar ended last week, but I hope that Paige and Sarah are able to continue these valuable workshops in one form or another in the years to come. For my final post in this series, I will discuss how I have attempted to incorporate the digital humanities into the course I am teaching this term, some of my success, as well as my failures.

Alt-Ac-Attack: Thoughts on Preparing for the Job Market

The job market is not great right now. We all know it. We don’t always want to think about it. And, since several years pass between the first year of grad school and the last year, it’s very easy to avoid thinking about it: just put your nose to the dissertation grindstone until that last frantic year when you have to look up from your work and look around. The market can change a lot in five, six, seven years as well: when I left undergrad in 2006, it wasn’t horrible. Now… it is, and it seems like grad programs are realizing this and making moves to address it. We are just starting to really assess this issue in my own department, and we’re trying to do this in two related ways: focus on preparations for the academic job market earlier in a student’s career AND accentuate other options that we’re not often taught to consider: alternative academic careers, in other words. In this post, I’d like to describe some of the issues and possible positive practices we discussed in a recent meeting among grad students in my department. I’d also really like to start a dialogue about what other departments are doing to help their graduates prepare for a more positive future after all their hard work.

about it. And, since several years pass between the first year of grad school and the last year, it’s very easy to avoid thinking about it: just put your nose to the dissertation grindstone until that last frantic year when you have to look up from your work and look around. The market can change a lot in five, six, seven years as well: when I left undergrad in 2006, it wasn’t horrible. Now… it is, and it seems like grad programs are realizing this and making moves to address it. We are just starting to really assess this issue in my own department, and we’re trying to do this in two related ways: focus on preparations for the academic job market earlier in a student’s career AND accentuate other options that we’re not often taught to consider: alternative academic careers, in other words. In this post, I’d like to describe some of the issues and possible positive practices we discussed in a recent meeting among grad students in my department. I’d also really like to start a dialogue about what other departments are doing to help their graduates prepare for a more positive future after all their hard work.

Alt-ac jobs unjustly get a bad rap: they’re spoken of with low tones, shaken heads, shrugged shoulders. We’re so focused on getting that increasingly unrealistic tenure-track professorship that anything else seems like some kind of failure. And it really, really shouldn’t. Jobs are hard to get in many professions, but variations using the same skill sets don’t seem to be looked down upon as much as they currently are in academia. So, one of the first problems to be fixed is this negative attitude towards jobs that require exactly the types of abilities at which we excel, jobs that would provide financial stability, health care, productivity, and a lot of genuine happiness. Concerns that interfere with considering these options early might include support from the department, committee expectations, discussions (or silences) amongst fellow grad students about such subjects, as well as simple confusion about how to market skills we already have or even how to find alternative career options. All these problems are fixable. My department has taken a first step by putting a recently-hired faculty member in charge to act as a go-to person to help students on an individual basis as they approach graduation as well as to hold various workshops and meetings related to academic and alt-ac job concerns. Overall, we’ve discussed some New School-Year’s Resolutions as we round out the end of our current semester:

Alt-ac jobs unjustly get a bad rap: they’re spoken of with low tones, shaken heads, shrugged shoulders. We’re so focused on getting that increasingly unrealistic tenure-track professorship that anything else seems like some kind of failure. And it really, really shouldn’t. Jobs are hard to get in many professions, but variations using the same skill sets don’t seem to be looked down upon as much as they currently are in academia. So, one of the first problems to be fixed is this negative attitude towards jobs that require exactly the types of abilities at which we excel, jobs that would provide financial stability, health care, productivity, and a lot of genuine happiness. Concerns that interfere with considering these options early might include support from the department, committee expectations, discussions (or silences) amongst fellow grad students about such subjects, as well as simple confusion about how to market skills we already have or even how to find alternative career options. All these problems are fixable. My department has taken a first step by putting a recently-hired faculty member in charge to act as a go-to person to help students on an individual basis as they approach graduation as well as to hold various workshops and meetings related to academic and alt-ac job concerns. Overall, we’ve discussed some New School-Year’s Resolutions as we round out the end of our current semester:

Start early. As I said, it’s really easy (and, let’s face it, enjoyable!) to get wrapped up in your research and to forget about where it might lead you after graduation. I, myself, am incredibly guilty of this. Just starting to poke around at what jobs are available from time to time can create awareness (without panic) and can also give you a sense of the timeline for applying to various positions. Start making the most of what you’re doing right now. Have faculty come observe your teaching in preparation for letters of recommendation. Get involved with committees in which you may already have an interest. Use summers to explore short-term alt-ac jobs that might require editing, grant-writing, teaching, etc.

Know what we have. We have so many skills that would make us fantastic professors. But they’d also make us lots of other fantastic kinds of professionals. We can speak in public and plan lessons and manage groups of people and think on our feet and make information interesting and read large amounts and synthesize and simplify and summarize and analyze and explain and entertain and proofread and edit and a hundred other things. But we don’t always translate what we do into these broader skills. Some of the future workshops we’ve discussed focus on this kind of translation: how to recognize our skills, how to use our writing skills for different types of writing, how to change a C.V. into a résumé, etc.

Speak and listen. Half the problem with both the impending trauma of the job  market and the search for alt-ac jobs is that we don’t talk enough about them. We don’t talk about what we think about putting our skills to use in different ways, and we don’t discuss what those different ways might be. What we’ve done, just by having a meeting to discuss the new faculty position and what we’d like it to cover, is to allow ourselves to talk and to listen to one another. This is huge. What’s more, we’re hoping to be able to speak and listen to those outside our current student and faculty population by contacting alumni who have pursued various career options with our same educations. We’ve begun to bring in speakers who can help us think about aspects of professional development and alt-ac careers. We’re planning mock interviews and job talks amongst ourselves, as well as more informal discussions about other aspects of applications.

market and the search for alt-ac jobs is that we don’t talk enough about them. We don’t talk about what we think about putting our skills to use in different ways, and we don’t discuss what those different ways might be. What we’ve done, just by having a meeting to discuss the new faculty position and what we’d like it to cover, is to allow ourselves to talk and to listen to one another. This is huge. What’s more, we’re hoping to be able to speak and listen to those outside our current student and faculty population by contacting alumni who have pursued various career options with our same educations. We’ve begun to bring in speakers who can help us think about aspects of professional development and alt-ac careers. We’re planning mock interviews and job talks amongst ourselves, as well as more informal discussions about other aspects of applications.

The job market is a sensitive subject for practically everyone right now, particularly for academics who have invested so much time and energy into a very specific career path. Yet, it’s also a concern near and dear to our hearts as we watch friends and colleagues struggle and prepare for struggles of our own. I am incredibly pleased and proud to be part of these steps to create a space for such an important conversation.

But, I know we are certainly not alone. I’d really like to open up this discussion to my fellow blog-readers: what steps have your departments taken to think about the job market and alt-ac careers? What have you found useful or frustrating in regards to the leap from graduate student to job seeker? What have you found really helpful in this process?

Helpful resources:

On Starting the Dissertation: The Reading List that Keeps on Listing

A few weeks ago, The Chronicle of Higher Education posted a series of brief discussions about the third year of studying for a PhD. The title is what caught my attention: “A Common Time to Get Stuck,” by Julia Miller Vick and Jennifer S. Furlong. The observation seems to be that the leap from coursework to exams or from exams to dissertation (typically the third year) causes a significant jolt in the way we’re used to learning and producing work, and I whole-heartedly agree. The third year for my department means that students have just completed their exams and are now faced with the daunting task of formulating a dissertation proposal and finally starting the long, hard work of diving right in. I thought I’d add my own two cents on what makes this such a pivotal, exciting, and (in some ways) frustrating and terrifying year.

A few weeks ago, The Chronicle of Higher Education posted a series of brief discussions about the third year of studying for a PhD. The title is what caught my attention: “A Common Time to Get Stuck,” by Julia Miller Vick and Jennifer S. Furlong. The observation seems to be that the leap from coursework to exams or from exams to dissertation (typically the third year) causes a significant jolt in the way we’re used to learning and producing work, and I whole-heartedly agree. The third year for my department means that students have just completed their exams and are now faced with the daunting task of formulating a dissertation proposal and finally starting the long, hard work of diving right in. I thought I’d add my own two cents on what makes this such a pivotal, exciting, and (in some ways) frustrating and terrifying year.

Furlong says, “The familiar rhythm of reading lists, paper submissions, and semester-long deadlines gives way to a more ambiguous challenge—developing an original research project that meets the standards for scholarship in an academic discipline.” Familiar is the perfect word for it: we’ve all been in school for decades… we know what how class works, we know how homework works, we know how writing papers works. I don’t know that I’d call it easy, but we at least know all the dance steps and that, somehow, it all gets done no matter how many all-nighters it takes.

Vick adds, “It is also a time when students have to start answering to themselves more than to their professors and mentors. After comprehensive exams are passed they need to become their own taskmasters and work without, in many cases, external deadlines and demands.” So, suddenly you go from having packed schedules, syllabi, and exam reading schedules to… anything and everything. Or, at least it feels that way. Suddenly, you have years of work ahead of you without a set structure, constructing an argument that could take on a life of its own at any moment. Anything could be useful, so you must read everything. All the books. This leads me to my next point.

A few days ago, I came across a second piece of online writing—this one a blog article on Book Riot— which seemed to speak directly to the title of the article in The Chronicle: “When You Realize You Can’t Read All the Things,” written by Jill Guccini. All the frustration of this title realization comes through as she describes the many situations in which you find yourself acquiring new books… but not actually reading them as they pile up into “mini cityscapes on your floor.” This is especially true for academics in the humanities, for whom reading is both work and play, and getting new books is both extremely pleasurable and sadly stressful. What a crime to leave them, unread, to get dusty and yellowed on the shelf… but I know I am guilty as charged.

Now, bear with me: these two articles are related. When you’re working short term on coursework or exams, you can find some solace in that you only have to keep it up until the deadline comes and goes. We would all study for exams forever if there weren’t a deadline to stop us, and thank god there is. I’m wondering if part of the  “getting stuck” Vick and Furlong talk about has to do with the few years of dissertation work begun in the third year feeling like forever and a somewhat narrow field feeling like “all the things.” So, if I’m writing about body parts in Frankenstein, then I have to read the novel and all the critical books and articles on it. Then I should read all about Mary Shelley and the Shelley circle and anyone who influenced that circle and maybe all of Shelley’s other work…and also follow up on this, this, and this footnote. Then, okay, body parts: I should read all the medical discourse when Shelley was writing and maybe what people thought before she was writing and also after she was writing, and maybe some of the current medical discourse on amputation and organ donations, and, why not, maybe some stuff on bodysnatching and army doctors. Now, what about any kind of literary theory: Kristeva and Lacan and Deleuze and Freud and Bakhtin. And theory on the history of the period and of novel form and novel circulation and the two different editions and where it was sold and how much it cost and what kind of paper it was printed on and who bought the first copy. And each article or book as an extensive bibliography that should be gone through with a fine-tooth comb. I’m being a little ridiculous, but see what I mean?

“getting stuck” Vick and Furlong talk about has to do with the few years of dissertation work begun in the third year feeling like forever and a somewhat narrow field feeling like “all the things.” So, if I’m writing about body parts in Frankenstein, then I have to read the novel and all the critical books and articles on it. Then I should read all about Mary Shelley and the Shelley circle and anyone who influenced that circle and maybe all of Shelley’s other work…and also follow up on this, this, and this footnote. Then, okay, body parts: I should read all the medical discourse when Shelley was writing and maybe what people thought before she was writing and also after she was writing, and maybe some of the current medical discourse on amputation and organ donations, and, why not, maybe some stuff on bodysnatching and army doctors. Now, what about any kind of literary theory: Kristeva and Lacan and Deleuze and Freud and Bakhtin. And theory on the history of the period and of novel form and novel circulation and the two different editions and where it was sold and how much it cost and what kind of paper it was printed on and who bought the first copy. And each article or book as an extensive bibliography that should be gone through with a fine-tooth comb. I’m being a little ridiculous, but see what I mean?

Beginning the dissertation is the ultimate in you-can’t-read-everything frustration because not only do you have a million things you want to read, but there’s the added pressure that you feel you need to read them in order to create something worthwhile. And Vick is right: yes, we’re answerable to our advisors and our committees and to future job applications, but at this point in the game, when all your work is chosen by you and made extremely important because of that, there is an incredible sense of self-worth but also a lot of nervousness in regards to living up to your own expectations. Can you ever read enough to satisfy yourself? The answer (and the point to this whole academic game we play) is no. I think what I’m learning as I’m still in this dangerous third year is that, no, you really can’t read all the things. Somehow that makes me feel a little better.

I would have loved to give better advice in this post rather than just some observations, but I feel too close to the beginning still to assess what is working and what isn’t. I’d like to invite fellow bloggers and readers to respond, though!

What worked for you when you were starting your dissertation that kept you from trying to “read all the things”?

The best tips I can give about preparing for comps

This is going to be a short and relatively easy post, which are the two things studying for the comprehensive exam is not. It’s been a grueling couple of months, and I admit studying for the comprehensive exam is stressing me out. Really stressing me out. Perhaps that’s not a surprise. Grad school is stressful. There’s teaching, conferences, essays, professionalization, publishing, networking, and constant reading. There’s very little money. But, the reading year has been particularly stressful. It’s the impending pressure of having to sit in a room with five people who will quiz me about one hundred and twenty books. Five people will evaluate me at once. It’s also a discussion that will either allow me to advance in the program, or will result in a stalled few months.

The logical part of my brain knows the exam is a wonderful opportunity to discuss great texts and float ideas. Other people have written wonderful posts about how to prepare for the exam. They encourage having an organized note-taking system and talking about books to everyone. I’m going to focus on how to relax enough in order to accomplish any of that. Here are some tips that I wish someone had drilled into my head during my first few weeks:

Get off of Facebook. There are tons of studies coming out that suggest anyone on Facebook judges themselves based on what other people’s lives appear to be like. We, as English people, can understand that. People edit their lives on social media, and the story can seem more real than the editing. I’ve found Facebook stress becomes more amplified when you spend eight to ten hours a day in a chair and your arms hurt from holding large texts close to your face. Looking at pictures of someone else just being outside, where there is sun, trees, animals, and plants, is suddenly hurtful. You’re inside, you can’t go outside because you should be reading, but you’re not reading; you’re on Facebook, where it seems everyone else is outside or having fun or having fun outside.